Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the national economy as a whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

Macroeconomics is a branch of economics that deals with the performance, structure, behavior, and decision-making of an economy as a whole. This includes regional, national, and global economies. Macroeconomists study topics such as output/GDP and national income, unemployment, price indices and inflation, consumption, saving, investment, energy, international trade, and international finance.

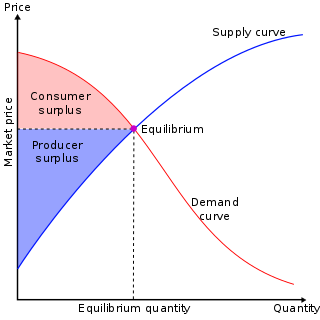

In economics, specifically general equilibrium theory, a perfect market, also known as an atomistic market, is defined by several idealizing conditions, collectively called perfect competition, or atomistic competition. In theoretical models where conditions of perfect competition hold, it has been demonstrated that a market will reach an equilibrium in which the quantity supplied for every product or service, including labor, equals the quantity demanded at the current price. This equilibrium would be a Pareto optimum.

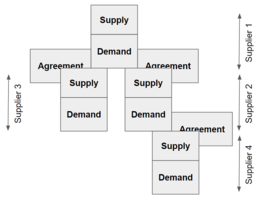

In economics, general equilibrium theory attempts to explain the behavior of supply, demand, and prices in a whole economy with several or many interacting markets, by seeking to prove that the interaction of demand and supply will result in an overall general equilibrium. General equilibrium theory contrasts with the theory of partial equilibrium, which analyzes a specific part of an economy while its other factors are held constant. In general equilibrium, constant influences are considered to be noneconomic, or in other words, considered to be beyond the scope of economic analysis. The noneconomic influences may change given changes in the economic factors however, and therefore the prediction accuracy of an equilibrium model may depend on the independence of the economic factors from noneconomic ones.

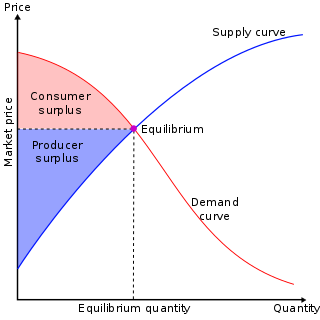

In mainstream economics, economic surplus, also known as total welfare or total social welfare or Marshallian surplus, is either of two related quantities:

The IS–LM model, or Hicks–Hansen model, is a two-dimensional macroeconomic model which is used as a pedagogical tool in macroeconomic teaching. The IS–LM model shows the relationship between interest rates and output in the short run in a closed economy. The intersection of the "investment–saving" (IS) and "liquidity preference–money supply" (LM) curves illustrates a "general equilibrium" where supposed simultaneous equilibria occur in both the goods and the money markets. The IS–LM model shows the importance of various demand shocks on output and consequently offers an explanation of changes in national income in the short run when prices are fixed or sticky. Hence, the model can be used as a tool to suggest potential levels for appropriate stabilisation policies. It is also used as a building block for the demand side of the economy in more comprehensive models like the AD–AS model.

This aims to be a complete article list of economics topics:

In economics, elasticity measures the responsiveness of one economic variable to a change in another. If the price elasticity of the demand of something is -2, a 10% increase in price causes the quantity demanded to fall by 20%. Elasticity in economics provides an understanding of changes in the behavior of the buyers and sellers with price changes. There are two types of elasticity for demand and supply, one is inelastic demand and supply and the other one is elastic demand and supply.

In economics, economic equilibrium is a situation in which economic forces such as supply and demand are balanced and in the absence of external influences the values of economic variables will not change. For example, in the standard text perfect competition, equilibrium occurs at the point at which quantity demanded and quantity supplied are equal.

In economics, aggregate demand (AD) or domestic final demand (DFD) is the total demand for final goods and services in an economy at a given time. It is often called effective demand, though at other times this term is distinguished. This is the demand for the gross domestic product of a country. It specifies the amount of goods and services that will be purchased at all possible price levels. Consumer spending, investment, corporate and government expenditure, and net exports make up the aggregate demand.

In economics, effective demand (ED) in a market is the demand for a product or service which occurs when purchasers are constrained in a different market. It contrasts with notional demand, which is the demand that occurs when purchasers are not constrained in any other market. In the aggregated market for goods in general, demand, notional or effective, is referred to as aggregate demand. The concept of effective supply parallels the concept of effective demand. The concept of effective demand or supply becomes relevant when markets do not continuously maintain equilibrium prices.

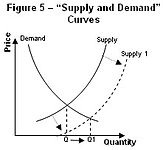

A demand curve is a graph depicting the inverse demand function, a relationship between the price of a certain commodity and the quantity of that commodity that is demanded at that price. Demand curves can be used either for the price-quantity relationship for an individual consumer, or for all consumers in a particular market.

In economics, tax incidence or tax burden is the effect of a particular tax on the distribution of economic welfare. Economists distinguish between the entities who ultimately bear the tax burden and those on whom the tax is initially imposed. The tax burden measures the true economic effect of the tax, measured by the difference between real incomes or utilities before and after imposing the tax, and taking into account how the tax causes prices to change. For example, if a 10% tax is imposed on sellers of butter, but the market price rises 8% as a result, most of the tax burden is on buyers, not sellers. The concept of tax incidence was initially brought to economists' attention by the French Physiocrats, in particular François Quesnay, who argued that the incidence of all taxation falls ultimately on landowners and is at the expense of land rent. Tax incidence is said to "fall" upon the group that ultimately bears the burden of, or ultimately suffers a loss from, the tax. The key concept of tax incidence is that the tax incidence or tax burden does not depend on where the revenue is collected, but on the price elasticity of demand and price elasticity of supply. As a general policy matter, the tax incidence should not violate the principles of a desirable tax system, especially fairness and transparency. The concept of tax incidence is used in political science and sociology to analyze the level of resources extracted from each income social stratum in order to describe how the tax burden is distributed among social classes. That allows one to derive some inferences about the progressive nature of the tax system, according to principles of vertical equity.

In economics, the long-run is a theoretical concept in which all markets are in equilibrium, and all prices and quantities have fully adjusted and are in equilibrium. The long-run contrasts with the short-run, in which there are some constraints and markets are not fully in equilibrium. More specifically, in microeconomics there are no fixed factors of production in the long-run, and there is enough time for adjustment so that there are no constraints preventing changing the output level by changing the capital stock or by entering or leaving an industry. This contrasts with the short-run, where some factors are variable and others are fixed, constraining entry or exit from an industry. In macroeconomics, the long-run is the period when the general price level, contractual wage rates, and expectations adjust fully to the state of the economy, in contrast to the short-run when these variables may not fully adjust.

In economics, demand is the quantity of a good that consumers are willing and able to purchase at various prices during a given time. The relationship between price and quantity demand is also called the demand curve. Demand for a specific item is a function of an item's perceived necessity, price, perceived quality, convenience, available alternatives, purchasers' disposable income and tastes, and many other options.

In economics, supply is the amount of a resource that firms, producers, labourers, providers of financial assets, or other economic agents are willing and able to provide to the marketplace or to an individual. Supply can be in produced goods, labour time, raw materials, or any other scarce or valuable object. Supply is often plotted graphically as a supply curve, with the price per unit on the vertical axis and quantity supplied as a function of price on the horizontal axis. This reversal of the usual position of the dependent variable and the independent variable is an unfortunate but standard convention.

The neoclassical synthesis (NCS), neoclassical–Keynesian synthesis, or just neo-Keynesianism was a neoclassical economics academic movement and paradigm in economics that worked towards reconciling the macroeconomic thought of John Maynard Keynes in his book The General Theory of Employment, Interest and Money (1936). It was formulated most notably by John Hicks (1937), Franco Modigliani (1944), and Paul Samuelson (1948), who dominated economics in the post-war period and formed the mainstream of macroeconomic thought in the 1950s, 60s, and 70s.

The AD–AS or aggregate demand–aggregate supply model is a widely used macroeconomic model that explains short-run and long-run economic changes through the relationship of aggregate demand (AD) and aggregate supply (AS) in a diagram. It coexists in an older and static version depicting the two variables output and price level, and in a newer dynamic version showing output and inflation.

Macroeconomic theory has its origins in the study of business cycles and monetary theory. In general, early theorists believed monetary factors could not affect real factors such as real output. John Maynard Keynes attacked some of these "classical" theories and produced a general theory that described the whole economy in terms of aggregates rather than individual, microeconomic parts. Attempting to explain unemployment and recessions, he noticed the tendency for people and businesses to hoard cash and avoid investment during a recession. He argued that this invalidated the assumptions of classical economists who thought that markets always clear, leaving no surplus of goods and no willing labor left idle.

This glossary of economics is a list of definitions of terms and concepts used in economics, its sub-disciplines, and related fields.