Related Research Articles

The large intestine, also known as the large bowel, is the last part of the gastrointestinal tract and of the digestive system in tetrapods. Water is absorbed here and the remaining waste material is stored in the rectum as feces before being removed by defecation. The colon is the longest portion of the large intestine, and the terms are often used interchangeably but most sources define the large intestine as the combination of the cecum, colon, rectum, and anal canal. Some other sources exclude the anal canal.

Dietary fiber or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by their solubility, viscosity, and fermentability, which affect how fibers are processed in the body. Dietary fiber has two main components: soluble fiber and insoluble fiber, which are components of plant-based foods, such as legumes, whole grains and cereals, vegetables, fruits, and nuts or seeds. A diet high in regular fiber consumption is generally associated with supporting health and lowering the risk of several diseases. Dietary fiber consists of non-starch polysaccharides and other plant components such as cellulose, resistant starch, resistant dextrins, inulin, lignins, chitins, pectins, beta-glucans, and oligosaccharides.

Defecation follows digestion, and is a necessary process by which organisms eliminate a solid, semisolid, or liquid waste material known as feces from the digestive tract via the anus or cloaca. The act has a variety of names ranging from the common, like pooping or crapping, to the technical, e.g. bowel movement, to the obscene (shitting), to the euphemistic, to the juvenile. The topic, usually avoided in polite company, can become the basis for some potty humor.

An enema, also known as a clyster, is an injection of fluid into the lower bowel by way of the rectum. The word enema can also refer to the liquid injected, as well as to a device for administering such an injection.

Constipation is a bowel dysfunction that makes bowel movements infrequent or hard to pass. The stool is often hard and dry. Other symptoms may include abdominal pain, bloating, and feeling as if one has not completely passed the bowel movement. Complications from constipation may include hemorrhoids, anal fissure or fecal impaction. The normal frequency of bowel movements in adults is between three per day and three per week. Babies often have three to four bowel movements per day while young children typically have two to three per day.

Laxatives, purgatives, or aperients are substances that loosen stools and increase bowel movements. They are used to treat and prevent constipation.

Fecal incontinence (FI), or in some forms encopresis, is a lack of control over defecation, leading to involuntary loss of bowel contents, both liquid stool elements and mucus, or solid feces. When this loss includes flatus (gas), it is referred to as anal incontinence. FI is a sign or a symptom, not a diagnosis. Incontinence can result from different causes and might occur with either constipation or diarrhea. Continence is maintained by several interrelated factors, including the anal sampling mechanism, and incontinence usually results from a deficiency of multiple mechanisms. The most common causes are thought to be immediate or delayed damage from childbirth, complications from prior anorectal surgery, altered bowel habits. An estimated 2.2% of community-dwelling adults are affected. However, reported prevalence figures vary. A prevalence of 8.39% among non-institutionalized U.S adults between 2005 and 2010 has been reported, and among institutionalized elders figures come close to 50%.

Colonoscopy or coloscopy is a medical procedure involving the endoscopic examination of the large bowel (colon) and the distal portion of the small bowel. This examination is performed using either a CCD camera or a fiber optic camera, which is mounted on a flexible tube and passed through the anus.

Encopresis is voluntary or involuntary passage of feces outside of toilet-trained contexts in children who are four years or older and after an organic cause has been excluded. Children with encopresis often leak stool into their undergarments.

Ileostomy is a stoma constructed by bringing the end or loop of small intestine out onto the surface of the skin, or the surgical procedure which creates this opening. Intestinal waste passes out of the ileostomy and is collected in an external ostomy system which is placed next to the opening. Ileostomies are usually sited above the groin on the right hand side of the abdomen.

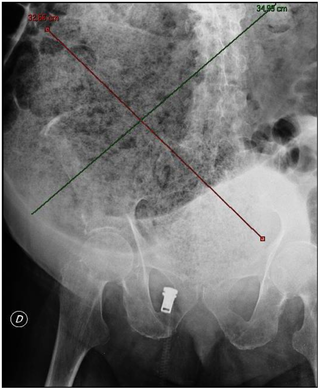

Virtual colonoscopy is the use of CT scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to produce two- and three-dimensional images of the colon, from the lowest part, the rectum, to the lower end of the small intestine, and to display the images on an electronic display device. The procedure is used to screen for colon cancer and polyps, and may detect diverticulosis. A virtual colonoscopy can provide 3D reconstructed endoluminal views of the bowel. VC provides a secondary benefit of revealing diseases or abnormalities outside the colon.

A fecal impaction or an impacted bowel is a solid, immobile bulk of feces that can develop in the rectum as a result of chronic constipation. Fecal impaction is a common result of neurogenic bowel dysfunction and causes immense discomfort and pain. Its treatment includes laxatives, enemas, and pulsed irrigation evacuation (PIE) as well as digital removal. It is not a condition that resolves without direct treatment.

Detoxification is a type of alternative-medicine treatment which aims to rid the body of unspecified "toxins" – substances that proponents claim accumulate in the body over time and have undesirable short-term or long-term effects on individual health. Activities commonly associated with detoxification include dieting, fasting, consuming exclusively or avoiding specific foods, colon cleansing, chelation therapy, certain kinds of IV therapy and the removal of dental fillings containing amalgam.

In the anatomy of humans and homologous primates, the descending colon is the part of the colon extending from the left colic flexure to the level of the iliac crest. The function of the descending colon in the digestive system is to store the remains of digested food that will be emptied into the rectum.

An anal plug is a medical device that is often used to treat fecal incontinence, the accidental passing of bowel moments, by physically blocking involuntary loss of fecal material. Fecal material such as feces are solid remains of food that does not get digested in the small intestines; rather, it is broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. Anal plugs vary in design and composition, but they are typically single-use, intra-anal, disposable devices made out of soft materials to contain fecal material and prevent it from leaking out of the rectum. The idea of an anal insert for fecal incontinence was first evaluated in a study of 10 participants with three different designs of anal inserts.

Sir William Arbuthnot Lane, 1st Baronet, CB, FRCS was a British surgeon and physician. He mastered orthopaedic, abdominal, and ear, nose and throat surgery, while designing new surgical instruments toward maximal asepsis. He thus introduced the "no-touch technique", and some of his designed instruments remain in use.

Human feces are the solid or semisolid remains of food that could not be digested or absorbed in the small intestine of humans, but has been further broken down by bacteria in the large intestine. It also contains bacteria and a relatively small amount of metabolic waste products such as bacterially altered bilirubin, and the dead epithelial cells from the lining of the gut. It is discharged through the anus during a process called defecation.

A coffee enema is the injection of coffee into the rectum and colon via the anus, i.e., as an enema. There is no scientific evidence to support any positive health claim for this practice, and medical authorities advise that the procedure may be dangerous.

Bowel management is the process which a person with a bowel disability uses to manage fecal incontinence or constipation. People who have a medical condition which impairs control of their defecation use bowel management techniques to choose a predictable time and place to evacuate. A simple bowel management technique might include diet control and establishing a toilet routine. As a more involved practice a person might use an enema to relieve themselves. Without bowel management, the person might either suffer from the feeling of not getting relief, or they might soil themselves.

Colon cleansing, also known as colon therapy, or colon hydrotherapy, or a colonic, or colonic irrigation encompasses a number of alternative medical therapies claimed to remove unspecified toxins from the colon and intestinal tract by removing supposed accumulations of feces. Colon cleansing in this context should not be confused with an enema which introduces fluid into the colon, often under mainstream medical supervision, for a limited number of purposes including severe constipation and medical imaging.

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Colon cleanses thrive despite scant proof". The Georgia Straight . Retrieved 2008-11-05.

- 1 2 3 4 Hochster H. (2007). ""Colon Health" Websites". Current Colorectal Cancer Reports. 2 (3): 105–106. doi:10.1007/s11888-006-0027-6. S2CID 195301831.

- 1 2 3 Joe Schwarcz (April 5, 2008). "I have a gut feeling something's wrong here". Montreal Gazette. Archived from the original on June 3, 2012.

- 1 2 Soergel, Dagobert; Tony Tse; Laura Slaughter (2004). "Helping Healthcare Consumers Understand: An "Interpretive Layer" for Finding and Making Sense of Medical Information" (PDF). MedInfo2004. IOS Press, Amsterdam. 107 (Pt 2): 931–5. PMID 15360949. Archived from the original on July 17, 2011. Retrieved 2012-08-31.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - 1 2 Uthman, Edward (7 January 1998). "Mucoid Plaque". Quackwatch . Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- 1 2 Friedlander, Ed. "Ed's Guide to Alternative Therapies: Colonics" . Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ↑ Sullivan-Fowler M (July 1995). "Doubtful theories, drastic therapies: autointoxication and faddism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries". J Hist Med Allied Sci. 50 (3): 364–90. doi:10.1093/jhmas/50.3.364. PMID 7665877.

- ↑ Bastedo WA (1932). "Colonic irrigations: their administration, therapeutic application and dangers". 98. JAMA: 736.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Ernst, E (June 1997). "Colonic irrigation and the theory of autointoxication: a triumph of ignorance over science". Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology . 24 (4): 196–198. doi: 10.1097/00004836-199706000-00002 . PMID 9252839.

- ↑ Müller-Lissner SA, Kamm MA, Scarpignato C, Wald A (January 2005). "Myths and misconceptions about chronic constipation". Am. J. Gastroenterol. 100 (1): 232–42. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.40885.x. PMID 15654804. S2CID 8060335.

- 1 2 Foreman, Judy (June 30, 2008). "Beware of colon cleansing claims". Los Angeles Times .

- ↑ Grady, Denise (May 23, 2000). "Cult of the Colon: From Little Liver Pills to Big Obsessions". New York Times .

- ↑ Anderson, Richard (2000). Cleanse & Purify Thyself, Books One and Two. Christobe Publishing.

- ↑ "The Detoxification Myth".