Stegosaurus is a genus of herbivorous, four-legged, armored dinosaur from the Late Jurassic, characterized by the distinctive kite-shaped upright plates along their backs and spikes on their tails. Fossils of the genus have been found in the western United States and in Portugal, where they are found in Kimmeridgian- to Tithonian-aged strata, dating to between 155 and 145 million years ago. Of the species that have been classified in the upper Morrison Formation of the western US, only three are universally recognized: S. stenops, S. ungulatus and S. sulcatus. The remains of over 80 individual animals of this genus have been found. Stegosaurus would have lived alongside dinosaurs such as Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, Camarasaurus and Allosaurus, the latter of which may have preyed on it.

The Natural History Museum in London is a museum that exhibits a vast range of specimens from various segments of natural history. It is one of three major museums on Exhibition Road in South Kensington, the others being the Science Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The Natural History Museum's main frontage, however, is on Cromwell Road.

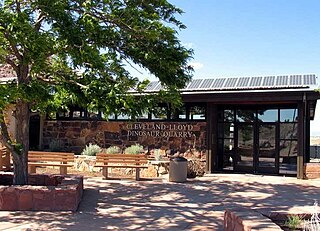

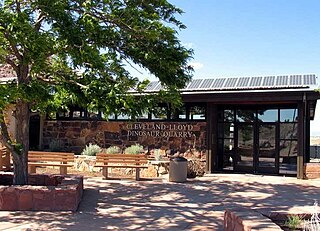

Jurassic National Monument, at the site of the Cleveland-Lloyd Dinosaur Quarry, well known for containing the densest concentration of Jurassic dinosaur fossils ever found, is a paleontological site located near Cleveland, Utah, in the San Rafael Swell, a part of the geological layers known as the Morrison Formation.

The UW–Madison Geology Museum (UWGM) is a geology and paleontology museum housed in Weeks Hall, in the southwest part of the University of Wisconsin–Madison campus. The museum's main undertakings are exhibits, outreach to the public, and research. It has the second highest attendance of any museum at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, exceeded only by the Chazen Museum of Art. The museum charges no admission.

The Paleontological Research Institution, or PRI, is a paleontological organization in Ithaca, New York, with a mission including both research and education. PRI is affiliated with Cornell University, houses one of the largest fossil collections in North America, and publishes, among other things, the oldest journal of paleontology in the western hemisphere, Bulletins of American Paleontology.

The Fukui Prefectural Dinosaur Museum, located in Katsuyama, Fukui, Japan, is one of the leading dinosaur museums in Asia that is renowned for its exhibits of fossil specimens of dinosaurs and paleontological research. It is sited in the Nagaoyama Park near the Kitadani Dinosaur Quarry that the Lower Cretaceous Kitadani Formation of the Tetori Group is cropped out and a large number of dinosaur remains including Fukuiraptor kitadaniensis and Fukuisaurus tetoriensis are found and excavated.

The Western Science Center (WSC), formerly the Western Center for Archaeology & Paleontology, is a museum located near Diamond Valley Lake in Hemet, California. The WSC is home to a large collection of Native American artifacts and Ice Age fossils that were unearthed at Diamond Valley Lake, including "Max", the largest mastodon found in the western United States, and "Xena", a Columbian mammoth, as well as dinosaur fossils recovered from New Mexico.

Bulletins of American Paleontology is a peer-reviewed scientific journal published by the Paleontological Research Institution and issued biannually that features monographs and dissertations in the field of paleontology and other related subjects. Founded by Gilbert Harris in 1895, it is the oldest continuously-published paleontological periodical in the Western Hemisphere, and one of the oldest in the world.

The Cayuga Nature Center (CNC) is an educational institution addressing nature and environmental issues. It is located on the west side of Cayuga Lake in Tompkins County, New York.

Paleontology in Michigan refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Michigan. During the Precambrian, the Upper Peninsula was home to filamentous algae. The remains it left behind are among the oldest known fossils in the world. During the early part of the Paleozoic Michigan was covered by a shallow tropical sea which was home to a rich invertebrate fauna including brachiopods, corals, crinoids, and trilobites. Primitive armored fishes and sharks were also present. Swamps covered the state during the Carboniferous. There are little to no sedimentary deposits in the state for an interval spanning from the Permian to the end of the Neogene. Deposition resumed as glaciers transformed the state's landscape during the Pleistocene. Michigan was home to large mammals like mammoths and mastodons at that time. The Holocene American mastodon, Mammut americanum, is the Michigan state fossil. The Petoskey stone, which is made of fossil coral, is the state stone of Michigan.

Paleontology in New York refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New York. New York has a very rich fossil record, especially from the Devonian. However, a gap in this record spans most of the Mesozoic and early Cenozoic.

Paleontology in Alabama refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Alabama. Pennsylvanian plant fossils are common, especially around coal mines. During the early Paleozoic, Alabama was at least partially covered by a sea that would end up being home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, corals, and graptolites. During the Devonian the local seas deepened and local wildlife became scarce due to their decreasing oxygen levels.

Paleontology in Nebraska refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Nebraska. Nebraska is world-famous as a source of fossils. During the early Paleozoic, Nebraska was covered by a shallow sea that was probably home to creatures like brachiopods, corals, and trilobites. During the Carboniferous, a swampy system of river deltas expanded westward across the state. During the Permian period, the state continued to be mostly dry land. The Triassic and Jurassic are missing from the local rock record, but evidence suggests that during the Cretaceous the state was covered by the Western Interior Seaway, where ammonites, fish, sea turtles, and plesiosaurs swam. The coasts of this sea were home to flowers and dinosaurs. During the early Cenozoic, the sea withdrew and the state was home to mammals like camels and rhinoceros. Ice Age Nebraska was subject to glacial activity and home to creatures like the giant bear Arctodus, horses, mammoths, mastodon, shovel-tusked proboscideans, and Saber-toothed cats. Local Native Americans devised mythical explanations for fossils like attributing them to water monsters killed by their enemies, the thunderbirds. After formally trained scientists began investigating local fossils, major finds like the Agate Springs mammal bone beds occurred. The Pleistocene mammoths Mammuthus primigenius, Mammuthus columbi, and Mammuthus imperator are the Nebraska state fossils.

Paleontology in New Mexico refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of New Mexico. The fossil record of New Mexico is exceptionally complete and spans almost the entire stratigraphic column. More than 3,300 different kinds of fossil organisms have been found in the state. Of these more than 700 of these were new to science and more than 100 of those were type species for new genera. During the early Paleozoic, southern and western New Mexico were submerged by a warm shallow sea that would come to be home to creatures including brachiopods, bryozoans, cartilaginous fishes, corals, graptolites, nautiloids, placoderms, and trilobites. During the Ordovician the state was home to algal reefs up to 300 feet high. During the Carboniferous, a richly vegetated island chain emerged from the local sea. Coral reefs formed in the state's seas while terrestrial regions of the state dried and were home to sand dunes. Local wildlife included Edaphosaurus, Ophiacodon, and Sphenacodon.

Paleontology in the United States refers to paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the United States. Paleontologists have found that at the start of the Paleozoic era, what is now "North" America was actually in the southern hemisphere. Marine life flourished in the country's many seas. Later the seas were largely replaced by swamps, home to amphibians and early reptiles. When the continents had assembled into Pangaea drier conditions prevailed. The evolutionary precursors to mammals dominated the country until a mass extinction event ended their reign.

The history of paleontology in the United States refers to the developments and discoveries regarding fossils found within or by people from the United States of America. Local paleontology began informally with Native Americans, who have been familiar with fossils for thousands of years. They both told myths about them and applied them to practical purposes. African slaves also contributed their knowledge; the first reasonably accurate recorded identification of vertebrate fossils in the new world was made by slaves on a South Carolina plantation who recognized the elephant affinities of mammoth molars uncovered there in 1725. The first major fossil discovery to attract the attention of formally trained scientists were the Ice Age fossils of Kentucky's Big Bone Lick. These fossils were studied by eminent intellectuals like France's George Cuvier and local statesmen and frontiersman like Daniel Boone, Benjamin Franklin, William Henry Harrison, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington. By the end of the 18th century possible dinosaur fossils had already been found.

This timeline of paleontology in Michigan is a chronologically ordered list events in the history of paleontological research occurring within or conducted by people from the U.S. state of Michigan.

Dippy is a composite Diplodocus skeleton in Pittsburgh's Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and the holotype of the species Diplodocus carnegii. It is considered the most famous single dinosaur skeleton in the world, due to the numerous plaster casts donated by Andrew Carnegie to several major museums around the world at the beginning of the 20th century.

The Mace Brown Museum of Natural History is a public natural history museum situated on the campus of The College of Charleston, a public liberal arts college in Charleston, South Carolina. Boasting a collection of over 30,000 vertebrate and invertebrate fossils, the museum focuses on the paleontology of the South Carolina Lowcountry. As an educational and research institution, the museum provides a unique resource for teaching and internationally respected research activities conducted at The College of Charleston. Admission to the museum is free, and donations are welcome. The museum has the holotype specimens of Coronodon, Cotylocara, and Inermorostrum, as well as the reference specimen of Ankylorhiza tiedemani