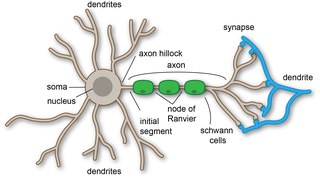

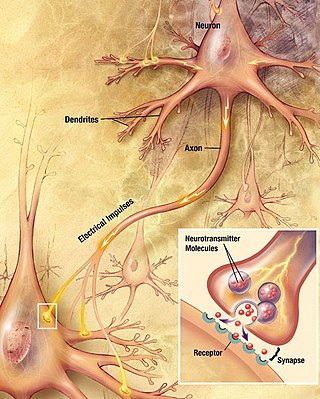

A dendrite or dendron is a branched protoplasmic extension of a nerve cell that propagates the electrochemical stimulation received from other neural cells to the cell body, or soma, of the neuron from which the dendrites project. Electrical stimulation is transmitted onto dendrites by upstream neurons via synapses which are located at various points throughout the dendritic tree.

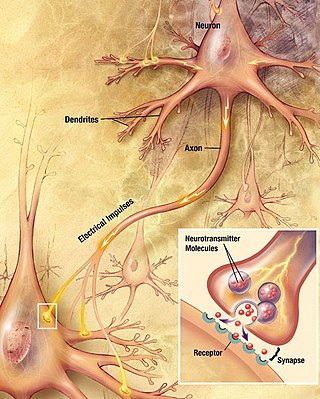

Within a nervous system, a neuron, neurone, or nerve cell is an electrically excitable cell that fires electric signals called action potentials across a neural network. Neurons communicate with other cells via synapses, which are specialized connections that commonly use minute amounts of chemical neurotransmitters to pass the electric signal from the presynaptic neuron to the target cell through the synaptic gap.

Chemical synapses are biological junctions through which neurons' signals can be sent to each other and to non-neuronal cells such as those in muscles or glands. Chemical synapses allow neurons to form circuits within the central nervous system. They are crucial to the biological computations that underlie perception and thought. They allow the nervous system to connect to and control other systems of the body.

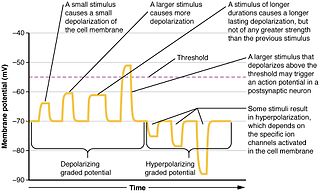

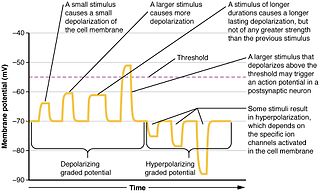

An action potential occurs when the membrane potential of a specific cell rapidly rises and falls. This depolarization then causes adjacent locations to similarly depolarize. Action potentials occur in several types of animal cells, called excitable cells, which include neurons, muscle cells, and in some plant cells. Certain endocrine cells such as pancreatic beta cells, and certain cells of the anterior pituitary gland are also excitable cells.

An inhibitory postsynaptic potential (IPSP) is a kind of synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron less likely to generate an action potential. The opposite of an inhibitory postsynaptic potential is an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP), which is a synaptic potential that makes a postsynaptic neuron more likely to generate an action potential. IPSPs can take place at all chemical synapses, which use the secretion of neurotransmitters to create cell-to-cell signalling. EPSPs and IPSPs compete with each other at numerous synapses of a neuron. This determines whether an action potential occurring at the presynaptic terminal produces an action potential at the postsynaptic membrane. Some common neurotransmitters involved in IPSPs are GABA and glycine.

In neuroscience, an excitatory postsynaptic potential (EPSP) is a postsynaptic potential that makes the postsynaptic neuron more likely to fire an action potential. This temporary depolarization of postsynaptic membrane potential, caused by the flow of positively charged ions into the postsynaptic cell, is a result of opening ligand-gated ion channels. These are the opposite of inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs), which usually result from the flow of negative ions into the cell or positive ions out of the cell. EPSPs can also result from a decrease in outgoing positive charges, while IPSPs are sometimes caused by an increase in positive charge outflow. The flow of ions that causes an EPSP is an excitatory postsynaptic current (EPSC).

An excitatory synapse is a synapse in which an action potential in a presynaptic neuron increases the probability of an action potential occurring in a postsynaptic cell. Neurons form networks through which nerve impulses travels, each neuron often making numerous connections with other cells of neurons. These electrical signals may be excitatory or inhibitory, and, if the total of excitatory influences exceeds that of the inhibitory influences, the neuron will generate a new action potential at its axon hillock, thus transmitting the information to yet another cell.

Pyramidal cells, or pyramidal neurons, are a type of multipolar neuron found in areas of the brain including the cerebral cortex, the hippocampus, and the amygdala. Pyramidal cells are the primary excitation units of the mammalian prefrontal cortex and the corticospinal tract. Pyramidal neurons are also one of two cell types where the characteristic sign, Negri bodies, are found in post-mortem rabies infection. Pyramidal neurons were first discovered and studied by Santiago Ramón y Cajal. Since then, studies on pyramidal neurons have focused on topics ranging from neuroplasticity to cognition.

The axon hillock is a specialized part of the cell body of a neuron that connects to the axon. It can be identified using light microscopy from its appearance and location in a neuron and from its sparse distribution of Nissl substance.

In physiology, electrotonus refers to the passive spread of charge inside a neuron and between cardiac muscle cells or smooth muscle cells. Passive means that voltage-dependent changes in membrane conductance do not contribute. Neurons and other excitable cells produce two types of electrical potential:

A neural circuit is a population of neurons interconnected by synapses to carry out a specific function when activated. Multiple neural circuits interconnect with one another to form large scale brain networks.

Molecular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience that observes concepts in molecular biology applied to the nervous systems of animals. The scope of this subject covers topics such as molecular neuroanatomy, mechanisms of molecular signaling in the nervous system, the effects of genetics and epigenetics on neuronal development, and the molecular basis for neuroplasticity and neurodegenerative diseases. As with molecular biology, molecular neuroscience is a relatively new field that is considerably dynamic.

Schaffer collaterals are axon collaterals given off by CA3 pyramidal cells in the hippocampus. These collaterals project to area CA1 of the hippocampus and are an integral part of memory formation and the emotional network of the Papez circuit, and of the hippocampal trisynaptic loop. It is one of the most studied synapses in the world and named after the Hungarian anatomist-neurologist Károly Schaffer.

An apical dendrite is a dendrite that emerges from the apex of a pyramidal cell. Apical dendrites are one of two primary categories of dendrites, and they distinguish the pyramidal cells from spiny stellate cells in the cortices. Pyramidal cells are found in the prefrontal cortex, the hippocampus, the entorhinal cortex, the olfactory cortex, and other areas. Dendrite arbors formed by apical dendrites are the means by which synaptic inputs into a cell are integrated. The apical dendrites in these regions contribute significantly to memory, learning, and sensory associations by modulating the excitatory and inhibitory signals received by the pyramidal cells.

In the nervous system, a synapse is a structure that permits a neuron to pass an electrical or chemical signal to another neuron or to the target effector cell.

Synaptic potential refers to the potential difference across the postsynaptic membrane that results from the action of neurotransmitters at a neuronal synapse. In other words, it is the “incoming” signal that a neuron receives. There are two forms of synaptic potential: excitatory and inhibitory. The type of potential produced depends on both the postsynaptic receptor, more specifically the changes in conductance of ion channels in the post synaptic membrane, and the nature of the released neurotransmitter. Excitatory post-synaptic potentials (EPSPs) depolarize the membrane and move the potential closer to the threshold for an action potential to be generated. Inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) hyperpolarize the membrane and move the potential farther away from the threshold, decreasing the likelihood of an action potential occurring. The Excitatory Post Synaptic potential is most likely going to be carried out by the neurotransmitters glutamate and acetylcholine, while the Inhibitory post synaptic potential will most likely be carried out by the neurotransmitters gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and glycine. In order to depolarize a neuron enough to cause an action potential, there must be enough EPSPs to both depolarize the postsynaptic membrane from its resting membrane potential to its threshold and counterbalance the concurrent IPSPs that hyperpolarize the membrane. As an example, consider a neuron with a resting membrane potential of -70 mV (millivolts) and a threshold of -50 mV. It will need to be raised 20 mV in order to pass the threshold and fire an action potential. The neuron will account for all the many incoming excitatory and inhibitory signals via summative neural integration, and if the result is an increase of 20 mV or more, an action potential will occur.

In neurophysiology, a dendritic spike refers to an action potential generated in the dendrite of a neuron. Dendrites are branched extensions of a neuron. They receive electrical signals emitted from projecting neurons and transfer these signals to the cell body, or soma. Dendritic signaling has traditionally been viewed as a passive mode of electrical signaling. Unlike its axon counterpart which can generate signals through action potentials, dendrites were believed to only have the ability to propagate electrical signals by physical means: changes in conductance, length, cross sectional area, etc. However, the existence of dendritic spikes was proposed and demonstrated by W. Alden Spencer, Eric Kandel, Rodolfo Llinás and coworkers in the 1960s and a large body of evidence now makes it clear that dendrites are active neuronal structures. Dendrites contain voltage-gated ion channels giving them the ability to generate action potentials. Dendritic spikes have been recorded in numerous types of neurons in the brain and are thought to have great implications in neuronal communication, memory, and learning. They are one of the major factors in long-term potentiation.

Summation, which includes both spatial summation and temporal summation, is the process that determines whether or not an action potential will be generated by the combined effects of excitatory and inhibitory signals, both from multiple simultaneous inputs, and from repeated inputs. Depending on the sum total of many individual inputs, summation may or may not reach the threshold voltage to trigger an action potential.

Cellular neuroscience is a branch of neuroscience concerned with the study of neurons at a cellular level. This includes morphology and physiological properties of single neurons. Several techniques such as intracellular recording, patch-clamp, and voltage-clamp technique, pharmacology, confocal imaging, molecular biology, two photon laser scanning microscopy and Ca2+ imaging have been used to study activity at the cellular level. Cellular neuroscience examines the various types of neurons, the functions of different neurons, the influence of neurons upon each other, and how neurons work together.

Nonsynaptic plasticity is a form of neuroplasticity that involves modification of ion channel function in the axon, dendrites, and cell body that results in specific changes in the integration of excitatory postsynaptic potentials and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. Nonsynaptic plasticity is a modification of the intrinsic excitability of the neuron. It interacts with synaptic plasticity, but it is considered a separate entity from synaptic plasticity. Intrinsic modification of the electrical properties of neurons plays a role in many aspects of plasticity from homeostatic plasticity to learning and memory itself. Nonsynaptic plasticity affects synaptic integration, subthreshold propagation, spike generation, and other fundamental mechanisms of neurons at the cellular level. These individual neuronal alterations can result in changes in higher brain function, especially learning and memory. However, as an emerging field in neuroscience, much of the knowledge about nonsynaptic plasticity is uncertain and still requires further investigation to better define its role in brain function and behavior.