Coronary artery disease (CAD), also called coronary heart disease (CHD), ischemic heart disease (IHD), myocardial ischemia, or simply heart disease, involves the reduction of blood flow to the heart muscle due to build-up of atherosclerotic plaque in the arteries of the heart. It is the most common of the cardiovascular diseases. Types include stable angina, unstable angina, and myocardial infarction.

A firefighter is a first responder trained in firefighting, primarily to control and extinguish fires that threaten life and property, as well as to rescue persons from confinement or dangerous situations. Male firefighters are sometimes referred to as firemen.

Sitting is a basic action and resting position in which the body weight is supported primarily by the bony ischial tuberosities with the buttocks in contact with the ground or a horizontal surface such as a chair seat, instead of by the lower limbs as in standing, squatting or kneeling. When sitting, the torso is more or less upright, although sometimes it can lean against other objects for a more relaxed posture.

An occupational injury is bodily damage resulting from working. The most common organs involved are the spine, hands, the head, lungs, eyes, skeleton, and skin. Occupational injuries can result from exposure to occupational hazards, such as temperature, noise, insect or animal bites, blood-borne pathogens, aerosols, hazardous chemicals, radiation, and occupational burnout.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is any disease involving the heart or blood vessels. CVDs constitute a class of diseases that includes: coronary artery diseases, heart failure, hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, carditis, aortic aneurysms, peripheral artery disease, thromboembolic disease, and venous thrombosis.

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and/or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like socializing, watching TV, playing video games, reading or using a mobile phone or computer for much of the day. A sedentary lifestyle contributes to poor health quality, diseases as well as many preventable causes of death.

Type A and Type B personality hypothesis describes two contrasting personality types. In this hypothesis, personalities that are more competitive, highly organized, ambitious, impatient, highly aware of time management, or aggressive are labeled Type A, while more relaxed, "receptive", less "neurotic" and "frantic" personalities are labeled Type B.

Health promotion is, as stated in the 1986 World Health Organization (WHO) Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion, the "process of enabling people to increase control over, and to improve their health."

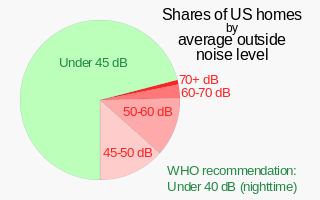

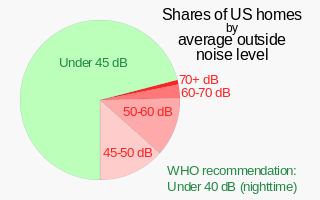

Noise health effects are the physical and psychological health consequences of regular exposure to consistent elevated sound levels. Noise from traffic, in particular, is considered by the World Health Organization to be one of the worst environmental stressors for humans, second only to air pollution. Elevated workplace or environmental noise can cause hearing impairment, tinnitus, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, annoyance, and sleep disturbance. Changes in the immune system and birth defects have been also attributed to noise exposure.

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are injuries or pain in the human musculoskeletal system, including the joints, ligaments, muscles, nerves, tendons, and structures that support limbs, neck and back. MSDs can arise from a sudden exertion, or they can arise from making the same motions repeatedly repetitive strain, or from repeated exposure to force, vibration, or awkward posture. Injuries and pain in the musculoskeletal system caused by acute traumatic events like a car accident or fall are not considered musculoskeletal disorders. MSDs can affect many different parts of the body including upper and lower back, neck, shoulders and extremities. Examples of MSDs include carpal tunnel syndrome, epicondylitis, tendinitis, back pain, tension neck syndrome, and hand-arm vibration syndrome.

Occupational health psychology (OHP) is an interdisciplinary area of psychology that is concerned with the health and safety of workers. OHP addresses a number of major topic areas including the impact of occupational stressors on physical and mental health, the impact of involuntary unemployment on physical and mental health, work-family balance, workplace violence and other forms of mistreatment, psychosocial workplace factors that affect accident risk and safety, and interventions designed to improve and/or protect worker health. Although OHP emerged from two distinct disciplines within applied psychology, namely, health psychology and industrial and organizational psychology, for a long time the psychology establishment, including leaders of industrial/organizational psychology, rarely dealt with occupational stress and employee health, creating a need for the emergence of OHP. OHP has also been informed by other disciplines, including occupational medicine, sociology, industrial engineering, and economics, as well as preventive medicine and public health. OHP is thus concerned with the relationship of psychosocial workplace factors to the development, maintenance, and promotion of workers' health and that of their families. The World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization estimate that exposure to long working hours causes an estimated 745,000 workers to die from ischemic heart disease and stroke in 2016, mediated by occupational stress.

The ICD-11 of the World Health Organization (WHO) describes occupational burnout as an occupational phenomenon resulting from chronic workplace stress that hasn't been successfully managed, with symptoms characterized by "feelings of energy depletion or exhaustion; increased mental distance from one’s job, or feelings of negativism or cynicism related to one's job; and reduced professional efficacy." It is classified as a mismatch between the challenges of work and a person's mental and physical resources, but is not recognized as a standalone medical condition, apart from the diagnosis of exhaustion disorder, which is only used in Sweden.

Occupational stress is psychological stress related to one's job. Occupational stress refers to a chronic condition. Occupational stress can be managed by understanding what the stressful conditions at work are and taking steps to remediate those conditions. Occupational stress can occur when workers do not feel supported by supervisors or coworkers, feel as if they have little control over the work they perform, or find that their efforts on the job are incommensurate with the job's rewards. Occupational stress is a concern for both employees and employers because stressful job conditions are related to employees' emotional well-being, physical health, and job performance. The World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization conducted a study. The results showed that exposure to long working hours, operates through increased psycho-social occupational stress. It is the occupational risk factor with the largest attributable burden of disease, according to these official estimates causing an estimated 745,000 workers to die from ischemic heart disease and stroke events in 2016.

Workplace health promotion is the combined efforts of employers, employees, and society to improve the mental and physical health and well-being of people at work. The term workplace health promotion denotes a comprehensive analysis and design of human and organizational work levels with the strategic aim of developing and improving health resources in an enterprise. The World Health Organization has prioritized the workplace as a setting for health promotion because of the large potential audience and influence on all spheres of a person's life. The Luxembourg Declaration provides that health and well-being of employees at work can be achieved through a combination of:

Occupational safety and health (OSH) or occupational health and safety (OHS) is a multidisciplinary field concerned with the safety, health, and welfare of people at work. OSH is related to the fields of occupational medicine and occupational hygiene and aligns with workplace health promotion initiatives. OSH also protects all the general public who may be affected by the occupational environment.

A psychosocial hazard or work stressor is any occupational hazard related to the way work is designed, organized and managed, as well as the economic and social contexts of work. Unlike the other three categories of occupational hazard, they do not arise from a physical substance, object, or hazardous energy.

Job strain is a form of psychosocial stress that occurs in the workplace. One of the most common forms of stress, it is characterized by a combination of low salaries, high demands, and low levels of control over things such as raises and paid time off. Stresses at work can be eustress, a positive type of stress, or distress, a negative type of stress. Job strain in the workplace has proved to result in poor psychological health, and eventually physical health. Job strain has been a recurring issue for years and affects men and women differently.

Employees who work overtime hours experience numerous mental, physical, and social effects. In a landmark study, the World Health Organization and the International Labour Organization estimated that over 745,000 people died from ischemic heart disease or stroke in 2016 as a result of having worked 55 hours or more per week. Significant effects include stress, lack of free time, poor work-life balance, and health risks. Employee performance levels could also be lowered. Long work hours could lead to tiredness, fatigue, and lack of attentiveness. As a result, suggestions have been proposed for risk mitigation.

The benefits of physical activity range widely. Most types of physical activity improve health and well-being.

Psychosocial safety climate (PSC) is a term used in organisational psychology that refers to the shared belief held by workers that their psychological health and safety is protected and supported by senior management. PSC builds on other work stress theories and concerns the corporate climate for worker psychological health and safety. Studies have found that a favourable PSC is associated with low rates of absenteeism and high productivity, while a poor climate is linked to high levels of workplace stress and job dissatisfaction. PSC can be promoted by organisational practices, policies and procedures that prioritise the psychosocial safety and wellbeing of workers. The theory has implications for the design of workplaces for the best possible outcomes for both workers and management.