Related Research Articles

Photography is the art, application, and practice of creating images by recording light, either electronically by means of an image sensor, or chemically by means of a light-sensitive material such as photographic film. It is employed in many fields of science, manufacturing, and business, as well as its more direct uses for art, film and video production, recreational purposes, hobby, and mass communication.

The following list comprises significant milestones in the development of photography technology.

Daguerreotype was the first publicly available photographic process; it was widely used during the 1840s and 1850s. "Daguerreotype" also refers to an image created through this process.

The collodion process is an early photographic process. The collodion process, mostly synonymous with the "collodion wet plate process", requires the photographic material to be coated, sensitized, exposed, and developed within the span of about fifteen minutes, necessitating a portable darkroom for use in the field. Collodion is normally used in its wet form, but it can also be used in its dry form, at the cost of greatly increased exposure time. The increased exposure time made the dry form unsuitable for the usual portraiture work of most professional photographers of the 19th century. The use of the dry form was mostly confined to landscape photography and other special applications where minutes-long exposure times were tolerable.

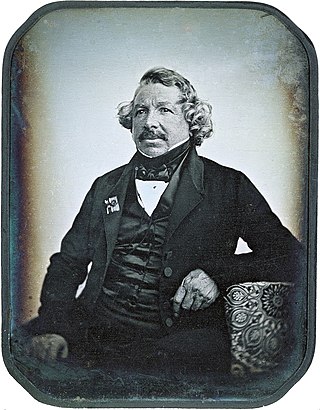

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre was a French artist and photographer, recognized for his invention of the eponymous daguerreotype process of photography. He became known as one of the fathers of photography. Though he is most famous for his contributions to photography, he was also an accomplished painter, scenic designer, and a developer of the diorama theatre.

Collodion is a flammable, syrupy solution of nitrocellulose in ether and alcohol. There are two basic types: flexible and non-flexible. The flexible type is often used as a surgical dressing or to hold dressings in place. When painted on the skin, collodion dries to form a flexible nitrocellulose film. While it is initially colorless, it discolors over time. Non-flexible collodion is often used in theatrical make-up. Collodion was also the basis of most wet-plate photography until it was superseded by modern gelatin emulsions.

Panoramic photography is a technique of photography, using specialized equipment or software, that captures images with horizontally elongated fields of view. It is sometimes known as wide format photography. The term has also been applied to a photograph that is cropped to a relatively wide aspect ratio, like the familiar letterbox format in wide-screen video.

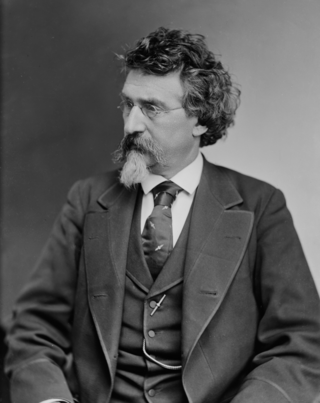

Mathew B. Brady was an American photographer. Known as one of the earliest and most famous photographers in American history, he is best known for his scenes of the Civil War. He studied under inventor Samuel Morse, who pioneered the daguerreotype technique in America. Brady opened his own studio in New York City in 1844, and went on to photograph U.S. presidents John Quincy Adams, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Van Buren, among other public figures.

The American Civil War was the most widely covered conflict of the 19th century. The images would provide posterity with a comprehensive visual record of the war and its leading figures, and make a powerful impression on the populace. Something not generally known by the public is the fact that roughly 70% of the war's documentary photography was captured by the twin lenses of a stereo camera. The American Civil War was the first war in history whose intimate reality would be brought home to the public, not only in newspaper depictions, album cards and cartes-de-visite, but in a popular new 3D format called a "stereograph," "stereocard" or "stereoview." Millions of these cards were produced and purchased by a public eager to experience the nature of warfare in a whole new way.

The gelatin silver process is the most commonly used chemical process in black-and-white photography, and is the fundamental chemical process for modern analog color photography. As such, films and printing papers available for analog photography rarely rely on any other chemical process to record an image. A suspension of silver salts in gelatin is coated onto a support such as glass, flexible plastic or film, baryta paper, or resin-coated paper. These light-sensitive materials are stable under normal keeping conditions and are able to be exposed and processed even many years after their manufacture. The "dry plate" gelatin process was an improvement on the collodion wet-plate process dominant from the 1850s–1880s, which had to be exposed and developed immediately after coating.

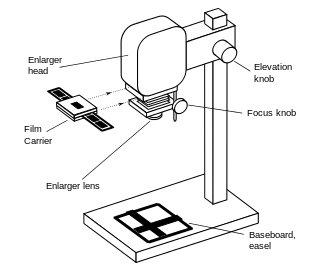

An enlarger is a specialized transparency projector used to produce photographic prints from film or glass negatives, or from transparencies.

The ambrotype, also known as a collodion positive in the UK, is a positive photograph on glass made by a variant of the wet plate collodion process. Like a print on paper, it is viewed by reflected light. Like the daguerreotype, which it replaced, and like the prints produced by a Polaroid camera, each is a unique original that could only be duplicated by using a camera to copy it.

A tintype, also known as a melanotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal, colloquially called 'tin', coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. It was introduced in 1853 by Adolphe Alexandre Martin in Paris, like the daguerreotype was fourteen years before by Daguerre. The daguerreotype was established and most popular by now, though the primary competition for the tintype would have been the ambrotype, that shared the same collodion process, but on a glass support instead of metal. Both found unequivocal, if not exclusive, acceptance in North America. Tintypes enjoyed their widest use during the 1860s and 1870s, but lesser use of the medium persisted into 1930s and it has been revived as a novelty and fine art form in the 21st century. It has been described as the first "truly democratic" medium for mass portraiture.

The science of photography is the use of chemistry and physics in all aspects of photography. This applies to the camera, its lenses, physical operation of the camera, electronic camera internals, and the process of developing film in order to take and develop pictures properly.

The carte de visite was a format of small photograph which was patented in Paris by photographer André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri in 1854, although first used by Louis Dodero.

The history of photography began with the discovery of two critical principles: The first is camera obscura image projection, the second is the discovery that some substances are visibly altered by exposure to light. There are no artifacts or descriptions that indicate any attempt to capture images with light sensitive materials prior to the 18th century.

The history of the camera began even before the introduction of photography. Cameras evolved from the camera obscura through many generations of photographic technology – daguerreotypes, calotypes, dry plates, film – to the modern day with digital cameras and camera phones.

Hand-colouring refers to any method of manually adding colour to a monochrome photograph, generally either to heighten the realism of the image or for artistic purposes. Hand-colouring is also known as hand painting or overpainting.

The conservation and restoration of photographs is the study of the physical care and treatment of photographic materials. It covers both efforts undertaken by photograph conservators, librarians, archivists, and museum curators who manage photograph collections at a variety of cultural heritage institutions, as well as steps taken to preserve collections of personal and family photographs. It is an umbrella term that includes both preventative preservation activities such as environmental control and conservation techniques that involve treating individual items. Both preservation and conservation require an in-depth understanding of how photographs are made, and the causes and prevention of deterioration. Conservator-restorers use this knowledge to treat photographic materials, stabilizing them from further deterioration, and sometimes restoring them for aesthetic purposes.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to photography:

References

- 1 2 3 Teicher, Jordan G. (2017-02-22). "The Hidden History of Photography and New York". Lens Blog. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Miles, Orvell (2016). Photography in America (First ed.). New York. ISBN 9780199314225. OCLC 904528804.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ D’Souza, Aruna (2021-08-17). "Smithsonian Acquires Rare Photographs From the First African American Studios". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331 . Retrieved 2021-08-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Photography and the Civil War, 1861–65". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2018-12-10.

- ↑ Wood, Gaby (2010-07-07). "Collodion photography: self-portrait in cyanide". ISSN 0307-1235 . Retrieved 2018-12-10.