Related Research Articles

Evidence-based medicine (EBM) is "the conscientious, explicit and judicious use of current best evidence in making decisions about the care of individual patients." The aim of EBM is to integrate the experience of the clinician, the values of the patient, and the best available scientific information to guide decision-making about clinical management. The term was originally used to describe an approach to teaching the practice of medicine and improving decisions by individual physicians about individual patients.

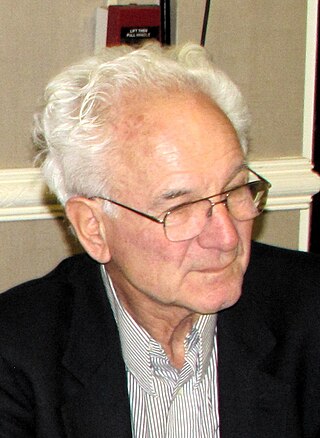

Peter H. Duesberg is a German-American molecular biologist and a professor of molecular and cell biology at the University of California, Berkeley. He is known for his early research into the genetic aspects of cancer. He is a proponent of AIDS denialism, the claim that HIV does not cause AIDS.

Scientific misconduct is the violation of the standard codes of scholarly conduct and ethical behavior in the publication of professional scientific research.

HIV/AIDS denialism is the belief, despite conclusive evidence to the contrary, that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) does not cause acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Some of its proponents reject the existence of HIV, while others accept that HIV exists but argue that it is a harmless passenger virus and not the cause of AIDS. Insofar as they acknowledge AIDS as a real disease, they attribute it to some combination of sexual behavior, recreational drugs, malnutrition, poor sanitation, haemophilia, or the effects of the medications used to treat HIV infection (antiretrovirals).

In published academic research, publication bias occurs when the outcome of an experiment or research study biases the decision to publish or otherwise distribute it. Publishing only results that show a significant finding disturbs the balance of findings in favor of positive results. The study of publication bias is an important topic in metascience.

In academic publishing, a retraction is a mechanism by which a published paper in an academic journal is flagged for being seriously flawed to the extent that their results and conclusions can no longer be relied upon. Retracted articles are not removed from the published literature but marked as retracted. In some cases it may be necessary to remove an article from publication, such as when the article is clearly defamatory, violates personal privacy, is the subject of a court order, or might pose a serious health risk to the general public.

Ben Michael Goldacre is a British physician, academic and science writer. He is the first Bennett Professor of Evidence-Based Medicine and director of the Bennett Institute for Applied Data Science at the University of Oxford. He is a founder of the AllTrials campaign and OpenTrials to require open science practices in clinical trials.

False balance, also bothsidesism, is a media bias in which journalists present an issue as being more balanced between opposing viewpoints than the evidence supports. Journalists may present evidence and arguments out of proportion to the actual evidence for each side, or may omit information that would establish one side's claims as baseless. False balance has been cited as a cause of misinformation.

The Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) is a British statutory advisory non-departmental public body, which was established under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.

Evidence-based practice is the idea that occupational practices ought to be based on scientific evidence. While seemingly obviously desirable, the proposal has been controversial, with some arguing that results may not specialize to individuals as well as traditional practices. Evidence-based practices have been gaining ground since the formal introduction of evidence-based medicine in 1992 and have spread to the allied health professions, education, management, law, public policy, architecture, and other fields. In light of studies showing problems in scientific research, there is also a movement to apply evidence-based practices in scientific research itself. Research into the evidence-based practice of science is called metascience.

Campbell's law is an adage developed by Donald T. Campbell, a psychologist and social scientist who often wrote about research methodology, which states:

The more any quantitative social indicator is used for social decision-making, the more subject it will be to corruption pressures and the more apt it will be to distort and corrupt the social processes it is intended to monitor.

Claims of a link between the MMR vaccine and autism have been extensively investigated and found to be false. The link was first suggested in the early 1990s and came to public notice largely as a result of the 1998 Lancet MMR autism fraud, characterised as "perhaps the most damaging medical hoax of the last 100 years". The fraudulent research paper authored by Andrew Wakefield and published in The Lancet falsely claimed the vaccine was linked to colitis and autism spectrum disorders. The paper was retracted in 2010 but is still cited by anti-vaxxers.

John P. A. Ioannidis is a Greek-American physician-scientist, writer and Stanford University professor who has made contributions to evidence-based medicine, epidemiology, and clinical research. Ioannidis studies scientific research itself, meta-research primarily in clinical medicine and the social sciences.

Alessandro Liberati was an Italian healthcare researcher and clinical epidemiologist, and founder of the Italian Cochrane Centre.

AllTrials is a project advocating that clinical research adopt the principles of open research. The project summarizes itself as "All trials registered, all results reported": that is, all clinical trials should be listed in a clinical trials registry, and their results should always be shared as open data.

Kirsti Elina Hemminki is a Finnish academic who was trained in medicine and public health. She has wide research experience in health services and epidemiological research. Her research interests include use, determinants and consequences of medical technology, particularly in the field of preventive services. Many of her examples come from women's and children's health and drugs (medicines). Her interests include health services trials, and how ethical and governance rules apply to them. Her other research interests have included research policy and research regulation.

Sir Patrick John Thompson Vallance is a British physician, scientist, and clinical pharmacologist who has worked in both academia and industry. He served as the Chief Scientific Adviser to the Government of the United Kingdom from 2018 to 2023.

Quantitative storytelling (QST) is a systematic approach used to explore the multiplicity of frames potentially legitimate in a scientific study or controversy. QST assumes that in an interconnected society multiple frameworks and worldviews are legitimately upheld by different entities and social actors. QST looks critically on models used in evidence-based policy (EBP. Such models are often reductionist, in the sense discussed by, in that tractability is achieved at the expenses of suppressing relevant available evidence. QST suggests corrective approaches to this practice.

The Lancet MMR autism fraud centered on the publication in February 1998 of a fraudulent research paper titled "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children" in The Lancet. The paper, authored by now discredited and deregistered Andrew Wakefield, and twelve coauthors, falsely claimed causative links between the MMR vaccine and colitis and between colitis and autism. The fraud was exposed in a lengthy Sunday Times investigation by reporter Brian Deer, resulting in the paper's retraction in February 2010 and Wakefield being struck off the UK medical register three months later. Wakefield reportedly stood to earn up to $43 million per year selling diagnostic kits for a non-existent syndrome he claimed to have discovered. He also held a patent to a rival vaccine at the time, and he had been employed by a lawyer representing parents in lawsuits against vaccine producers.

Alternative medicine describes any practice which aims to achieve the healing effects of medicine, but which lacks biological plausibility and is untested or untestable. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), integrated medicine or integrative medicine (IM), and holistic medicine are among many rebrandings of the same phenomenon.

References

- ↑ Strassheim, Holger; Kettunen, Pekka (2014-05-01). "When does evidence-based policy turn into policy-based evidence? Configurations, contexts and mechanisms". Evidence & Policy: A Journal of Research, Debate and Practice. 10 (2): 259–277. doi:10.1332/174426514X13990433991320.

- ↑ Parkhurst, Justin O. (4 October 2016). The politics of evidence : from evidence-based policy to the good governance of evidence. London. ISBN 978-1-317-38086-3. OCLC 963180218.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Marmot, Michael G (2004-04-17). "Evidence based policy or policy based evidence?". BMJ: British Medical Journal. 328 (7445): 906–907. doi:10.1136/bmj.328.7445.906. ISSN 0959-8138. PMC 390150 . PMID 15087324.

- ↑ Hughes, Caitlin E. (2007-01-01). "Evidence-based policy or policy-based evidence? The role of evidence in the development and implementation of the Illicit Drug Diversion Initiative". Drug and Alcohol Review. 26 (4): 363–368. doi: 10.1080/09595230701373859 . ISSN 0959-5236. PMID 17564871.

- ↑ Boden, Rebecca; Epstein, Debbie (2006). "Managing the research imagination? Globalisation and research in higher education". Globalisation, Societies and Education. 4 (2): 223–236. doi:10.1080/14767720600752619. S2CID 144077070.

- ↑ House of Commons Science and Technology Committee: Scientific Advice, Risk and Evidence Based Policy Making, paragraph 89

- ↑ Position paper for AHRC by Oliver Bennett Archived September 28, 2007, at the Wayback Machine