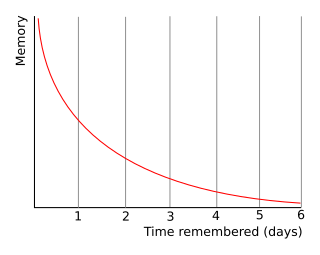

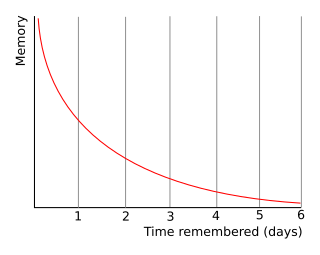

The forgetting curve hypothesizes the decline of memory retention in time. This curve shows how information is lost over time when there is no attempt to retain it. A related concept is the strength of memory that refers to the durability that memory traces in the brain. The stronger the memory, the longer period of time that a person is able to recall it. A typical graph of the forgetting curve purports to show that humans tend to halve their memory of newly learned knowledge in a matter of days or weeks unless they consciously review the learned material.

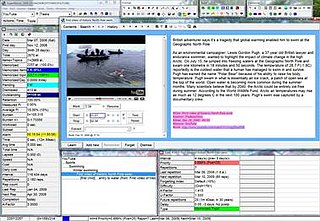

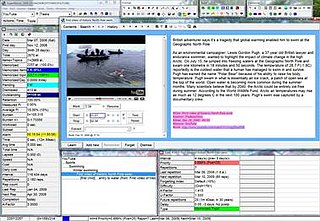

Incremental reading is a software-assisted method for learning and retaining information from reading, which involves the creation of flashcards out of electronic articles. "Incremental reading" means "reading in portions". Instead of a linear reading of articles one at a time, the method works by keeping a large list of electronic articles or books and reading parts of several articles in each session. The user prioritizes articles in the reading list. During reading, key points of articles are broken up into flashcards, which are then learned and reviewed over an extended period with the help of a spaced repetition algorithm.

Long-term memory (LTM) is the stage of the Atkinson–Shiffrin memory model in which informative knowledge is held indefinitely. It is defined in contrast to sensory memory, the initial stage, and short-term or working memory, the second stage, which persists for about 18 to 30 seconds. LTM is grouped into two categories known as explicit memory and implicit memory. Explicit memory is broken down into episodic and semantic memory, while implicit memory includes procedural memory and emotional conditioning.

SuperMemo is a learning method and software package developed by SuperMemo World and SuperMemo R&D with Piotr Woźniak in Poland from 1985 to the present. It is based on research into long-term memory, and is a practical application of the spaced repetition learning method that has been proposed for efficient instruction by a number of psychologists as early as in the 1930s.

Recall in memory refers to the mental process of retrieval of information from the past. Along with encoding and storage, it is one of the three core processes of memory. There are three main types of recall: free recall, cued recall and serial recall. Psychologists test these forms of recall as a way to study the memory processes of humans and animals. Two main theories of the process of recall are the two-stage theory and the theory of encoding specificity.

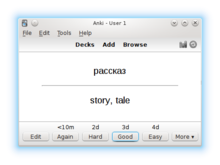

A flashcard or flash card is a card bearing information on both sides, which is intended to be used as an aid in memorization. Each flashcard typically bears a question or definition on one side and an answer or target term on the other. Flashcards are often used to memorize vocabulary, historical dates, formulae or any subject matter that can be learned via a question-and-answer format. Flashcards can be virtual, or physical.

The interference theory is a theory regarding human memory. Interference occurs in learning. The notion is that memories encoded in long-term memory (LTM) are forgotten and cannot be retrieved into short-term memory (STM) because either memory could interfere with the other. There is an immense number of encoded memories within the storage of LTM. The challenge for memory retrieval is recalling the specific memory and working in the temporary workspace provided in STM. Retaining information regarding the relevant time of encoding memories into LTM influences interference strength. There are two types of interference effects: proactive and retroactive interference.

The spacing effect demonstrates that learning is more effective when study sessions are spaced out. This effect shows that more information is encoded into long-term memory by spaced study sessions, also known as spaced repetition or spaced presentation, than by massed presentation ("cramming").

The testing effect suggests long-term memory is increased when part of the learning period is devoted to retrieving information from memory. It is different from the more general practice effect, defined in the APA Dictionary of Psychology as "any change or improvement that results from practice or repetition of task items or activities."

Study skills or study strategies are approaches applied to learning. Study skills are an array of skills which tackle the process of organizing and taking in new information, retaining information, or dealing with assessments. They are discrete techniques that can be learned, usually in a short time, and applied to all or most fields of study. More broadly, any skill which boosts a person's ability to study, retain and recall information which assists in and passing exams can be termed a study skill, and this could include time management and motivational techniques.

The generation effect is a phenomenon whereby information is better remembered if it is generated from one's own mind rather than simply read. Researchers have struggled to account for why the generated information is better recalled than read information, but no single explanation has been sufficient to explain everything.

Studying in an educational context refers to the process of gaining mastery of a certain area of information. Study software then is any program which allows students to improve the time they spend thinking about, learning and studying that information.

Anki is a free and open-source flashcard program. It uses techniques from cognitive science such as active recall testing and spaced repetition to aid the user in memorization. The name comes from the Japanese word for "memorization".

Metamemory or Socratic awareness, a type of metacognition, is both the introspective knowledge of one's own memory capabilities and the processes involved in memory self-monitoring. This self-awareness of memory has important implications for how people learn and use memories. When studying, for example, students make judgments of whether they have successfully learned the assigned material and use these decisions, known as "judgments of learning", to allocate study time.

Memory improvement is the act of enhancing one's memory. Research on improving memory is driven by amnesia, age-related memory loss, and people’s desire to enhance their memory. Research involved in memory improvement has also worked to determine what factors influence memory and cognition. There are many different techniques to improve memory some of which include cognitive training, psychopharmacology, diet, stress management, and exercise. Each technique can improve memory in different ways.

Memory gaps and errors refer to the incorrect recall, or complete loss, of information in the memory system for a specific detail and/or event. Memory errors may include remembering events that never occurred, or remembering them differently from the way they actually happened. These errors or gaps can occur due to a number of different reasons, including the emotional involvement in the situation, expectations and environmental changes. As the retention interval between encoding and retrieval of the memory lengthens, there is an increase in both the amount that is forgotten, and the likelihood of a memory error occurring.

Distributed practice is a learning strategy, where practice is broken up into a number of short sessions over a longer period of time. Humans and other animals learn items in a list more effectively when they are studied in several sessions spread out over a long period of time, rather than studied repeatedly in a short period of time, a phenomenon called the spacing effect. The opposite, massed practice, consists of fewer, longer training sessions and is generally a less effective method of learning. For example, when studying for an exam, dispersing your studying more frequently over a larger period of time will result in more effective learning than intense study the night before.

Elaborative encoding is a mnemonic system which uses some form of elaboration, such as an emotional cue, to assist in the retention of memories and knowledge. In this system one attaches an additional piece of information to a memory task which makes it easier to recall. For instance, one may recognize a face easier if character traits are also imparted about the person at the same time.

A desirable difficulty is a learning task that requires a considerable but desirable amount of effort, thereby improving long-term performance. It is also described as a learning level achieved through a sequence of learning tasks and feedback that lead to enhanced learning and transfer.

The forward testing effect, also known as test potentiated new learning, is a psychological learning theory which suggests that testing old information can improve learning of new information. Unlike traditional learning theories in educational psychology which have established the positive effect testing has when later attempting to retrieve the same information, the forward testing effect instead suggests that the testing experience itself possesses unique benefits which enhance the learning of new information. This memory effect is also distinct from the 'practice effect' which typically refers to an observed improvement which results from repetition and restudy, as the testing itself is considered as the catalyst for improved recall. Instead, this theory suggests that testing serves not only as a tool for assessment but as a learning tool which can aid in memory recall. The forward testing effect indicates that educators should encourage students to study using testing techniques rather than restudying information repeatedly.