In physics, the cross section is a measure of the probability that a specific process will take place in a collision of two particles. For example, the Rutherford cross-section is a measure of probability that an alpha particle will be deflected by a given angle during an interaction with an atomic nucleus. Cross section is typically denoted σ (sigma) and is expressed in units of area, more specifically in barns. In a way, it can be thought of as the size of the object that the excitation must hit in order for the process to occur, but more exactly, it is a parameter of a stochastic process.

A centripetal force is a force that makes a body follow a curved path. The direction of the centripetal force is always orthogonal to the motion of the body and towards the fixed point of the instantaneous center of curvature of the path. Isaac Newton described it as "a force by which bodies are drawn or impelled, or in any way tend, towards a point as to a centre". In Newtonian mechanics, gravity provides the centripetal force causing astronomical orbits.

In particle physics, the electroweak interaction or electroweak force is the unified description of two of the four known fundamental interactions of nature: electromagnetism (electromagnetic interaction) and the weak interaction. Although these two forces appear very different at everyday low energies, the theory models them as two different aspects of the same force. Above the unification energy, on the order of 246 GeV, they would merge into a single force. Thus, if the temperature is high enough – approximately 1015 K – then the electromagnetic force and weak force merge into a combined electroweak force. During the quark epoch (shortly after the Big Bang), the electroweak force split into the electromagnetic and weak force. It is thought that the required temperature of 1015 K has not been seen widely throughout the universe since before the quark epoch, and currently the highest human-made temperature in thermal equilibrium is around 5.5x1012 K (from the Large Hadron Collider).

In mathematics, a spherical coordinate system is a coordinate system for three-dimensional space where the position of a given point in space is specified by three numbers, : the radial distance of the radial liner connecting the point to the fixed point of origin ; the polar angle θ of the radial line r; and the azimuthal angle φ of the radial line r.

The Navier–Stokes equations are partial differential equations which describe the motion of viscous fluid substances. They were named after French engineer and physicist Claude-Louis Navier and the Irish physicist and mathematician George Gabriel Stokes. They were developed over several decades of progressively building the theories, from 1822 (Navier) to 1842–1850 (Stokes).

In the mathematical field of differential geometry, a metric tensor is an additional structure on a manifold M that allows defining distances and angles, just as the inner product on a Euclidean space allows defining distances and angles there. More precisely, a metric tensor at a point p of M is a bilinear form defined on the tangent space at p, and a metric field on M consists of a metric tensor at each point p of M that varies smoothly with p.

In physics, a wave vector is a vector used in describing a wave, with a typical unit being cycle per metre. It has a magnitude and direction. Its magnitude is the wavenumber of the wave, and its direction is perpendicular to the wavefront. In isotropic media, this is also the direction of wave propagation.

The Kerr–Newman metric is the most general asymptotically flat and stationary solution of the Einstein–Maxwell equations in general relativity that describes the spacetime geometry in the region surrounding an electrically charged and rotating mass. It generalizes the Kerr metric by taking into account the field energy of an electromagnetic field, in addition to describing rotation. It is one of a large number of various different electrovacuum solutions; that is, it is a solution to the Einstein–Maxwell equations that account for the field energy of an electromagnetic field. Such solutions do not include any electric charges other than that associated with the gravitational field, and are thus termed vacuum solutions.

Stokes flow, also named creeping flow or creeping motion, is a type of fluid flow where advective inertial forces are small compared with viscous forces. The Reynolds number is low, i.e. . This is a typical situation in flows where the fluid velocities are very slow, the viscosities are very large, or the length-scales of the flow are very small. Creeping flow was first studied to understand lubrication. In nature, this type of flow occurs in the swimming of microorganisms and sperm. In technology, it occurs in paint, MEMS devices, and in the flow of viscous polymers generally.

In mathematics, a change of variables is a basic technique used to simplify problems in which the original variables are replaced with functions of other variables. The intent is that when expressed in new variables, the problem may become simpler, or equivalent to a better understood problem.

A theoretical motivation for general relativity, including the motivation for the geodesic equation and the Einstein field equation, can be obtained from special relativity by examining the dynamics of particles in circular orbits about the Earth. A key advantage in examining circular orbits is that it is possible to know the solution of the Einstein Field Equation a priori. This provides a means to inform and verify the formalism.

A pendulum is a body suspended from a fixed support so that it swings freely back and forth under the influence of gravity. When a pendulum is displaced sideways from its resting, equilibrium position, it is subject to a restoring force due to gravity that will accelerate it back towards the equilibrium position. When released, the restoring force acting on the pendulum's mass causes it to oscillate about the equilibrium position, swinging it back and forth. The mathematics of pendulums are in general quite complicated. Simplifying assumptions can be made, which in the case of a simple pendulum allow the equations of motion to be solved analytically for small-angle oscillations.

The history of Lorentz transformations comprises the development of linear transformations forming the Lorentz group or Poincaré group preserving the Lorentz interval and the Minkowski inner product .

In geometry, various formalisms exist to express a rotation in three dimensions as a mathematical transformation. In physics, this concept is applied to classical mechanics where rotational kinematics is the science of quantitative description of a purely rotational motion. The orientation of an object at a given instant is described with the same tools, as it is defined as an imaginary rotation from a reference placement in space, rather than an actually observed rotation from a previous placement in space.

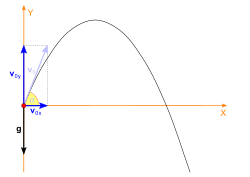

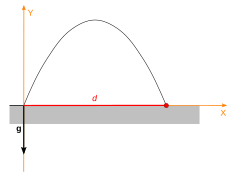

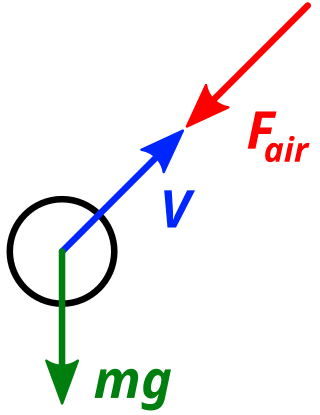

In physics, a projectile launched with specific initial conditions will have a range. It may be more predictable assuming a flat Earth with a uniform gravity field, and no air resistance. The horizontal ranges of a projectile are equal for two complementary angles of projection with the same velocity.

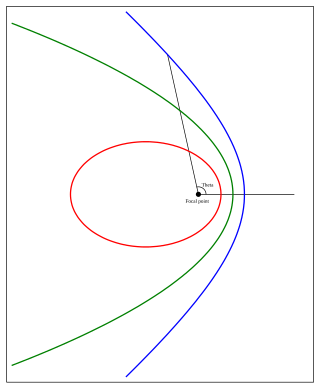

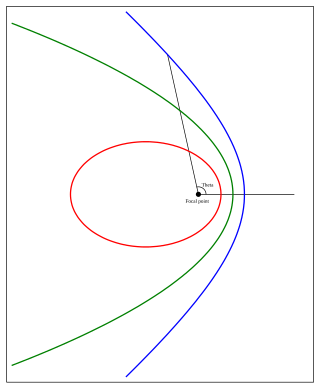

In celestial mechanics, a Kepler orbit is the motion of one body relative to another, as an ellipse, parabola, or hyperbola, which forms a two-dimensional orbital plane in three-dimensional space. A Kepler orbit can also form a straight line. It considers only the point-like gravitational attraction of two bodies, neglecting perturbations due to gravitational interactions with other objects, atmospheric drag, solar radiation pressure, a non-spherical central body, and so on. It is thus said to be a solution of a special case of the two-body problem, known as the Kepler problem. As a theory in classical mechanics, it also does not take into account the effects of general relativity. Keplerian orbits can be parametrized into six orbital elements in various ways.

In fluid dynamics, the Oseen equations describe the flow of a viscous and incompressible fluid at small Reynolds numbers, as formulated by Carl Wilhelm Oseen in 1910. Oseen flow is an improved description of these flows, as compared to Stokes flow, with the (partial) inclusion of convective acceleration.

In physics, Lagrangian mechanics is a formulation of classical mechanics founded on the stationary-action principle. It was introduced by the Italian-French mathematician and astronomer Joseph-Louis Lagrange in his presentation to the Turin Academy of Science in 1760 culminating in his 1788 grand opus, Mécanique analytique.

In fluid dynamics, Green's law, named for 19th-century British mathematician George Green, is a conservation law describing the evolution of non-breaking, surface gravity waves propagating in shallow water of gradually varying depth and width. In its simplest form, for wavefronts and depth contours parallel to each other, it states:

In fluid dynamics, Taylor scraping flow is a type of two-dimensional corner flow occurring when one of the wall is sliding over the other with constant velocity, named after G. I. Taylor.