Altaic is a controversial proposed language family that would include the Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic language families and possibly also the Japonic and Koreanic languages. The hypothetical language family has long been rejected by most comparative linguists, although it continues to be supported by a small but stable scholarly minority. Speakers of the constituent languages are currently scattered over most of Asia north of 35° N and in some eastern parts of Europe, extending in longitude from the Balkan Peninsula to Japan. The group is named after the Altai mountain range in the center of Asia.

The Turkic languages are a language family of more than 35 documented languages, spoken by the Turkic peoples of Eurasia from Eastern Europe and Southern Europe to Central Asia, East Asia, North Asia (Siberia), and West Asia. The Turkic languages originated in a region of East Asia spanning from Mongolia to Northwest China, where Proto-Turkic is thought to have been spoken, from where they expanded to Central Asia and farther west during the first millennium. They are characterized as a dialect continuum.

Ural-Altaic, Uralo-Altaic, Uraltaic, or Turanic is a linguistic convergence zone and abandoned language-family proposal uniting the Uralic and the Altaic languages. It is now generally agreed that even the Altaic languages do not share a common descent: the similarities between Turkic, Mongolic and Tungusic are better explained by diffusion and borrowing. Just as in Altaic, the internal structure of the Uralic family has been debated since the family was first proposed. Doubts about the validity of most or all of the proposed higher-order Uralic branchings are becoming more common. The term continues to be used for the central Eurasian typological, grammatical and lexical convergence zone.

The Mongolic languages are a language family spoken by the Mongolic peoples in Eastern Europe, Central Asia, North Asia and East Asia, mostly in Mongolia and surrounding areas and in Kalmykia and Buryatia. The best-known member of this language family, Mongolian, is the primary language of most of the residents of Mongolia and the Mongol residents of Inner Mongolia, with an estimated 5.7+ million speakers.

Bashkir or Bashkort is a Turkic language belonging to the Kipchak branch. It is co-official with Russian in Bashkortostan. It is spoken by 1.09 million native speakers in Russia, as well as in Ukraine, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Estonia and other neighboring post-Soviet states, and among the Bashkir diaspora. It has three dialect groups: Southern, Eastern and Northwestern.

Volga Bulgaria or Volga–Kama Bulgaria was a historical Bulgar state that existed between the 9th and 13th centuries around the confluence of the Volga and Kama River, in what is now European Russia. Volga Bulgaria was a multi-ethnic state with large numbers of Bulgars, Finno-Ugrians, Varangians and East Slavs. Its strategic position allowed it to create a local trade monopoly with Norse, Cumans, and Pannonian Avars.

The Chuvash people, plural: чӑвашсем, çăvaşsem; Russian: чува́ши ) are a Turkic ethnic group, a branch of the Ogurs, native to an area stretching from the Idel-Ural (Volga-Ural) region to Siberia.

Bulgar is an extinct Oghuric Turkic language spoken by the Bulgars.

Chuvash is a Turkic language spoken in European Russia, primarily in the Chuvash Republic and adjacent areas. It is the only surviving member of the Oghur branch of Turkic languages, one of the two principal branches of the Turkic family.

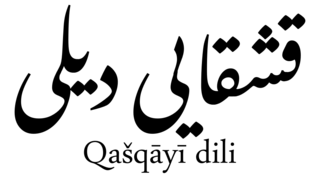

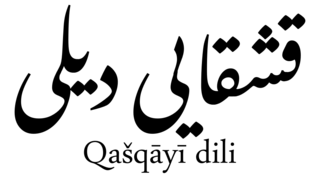

Qashqai is an Oghuz Turkic language spoken by the Qashqai people, an ethnic group living mainly in the Fars Province of Southern Iran. Encyclopædia Iranica regards Qashqai as an independent third group of dialects within the Southwestern Turkic language group. It is known to speakers as Turki. Estimates of the number of Qashqai speakers vary. Ethnologue gave a figure of 1.0 million in 2021.

The Onoghurs, Onoğurs, or Oğurs were Turkic nomadic equestrians who flourished in the Pontic–Caspian steppe and the Volga region between 5th and 7th century, and spoke the Oghuric language.

Old Siberian Turkic, generally known as East Old Turkic and often shortened to Old Turkic, was a Siberian Turkic language spoken around East Turkistan and Mongolia. It was first discovered in inscriptions originating from the Second Turkic Khaganate, and later the Uyghur Khaganate, making it the earliest attested Common Turkic language. In terms of the datability of extant written sources, the period of Old Turkic can be dated from slightly before 720 AD to the Mongol invasions of the 13th century. Old Turkic can generally be split into two dialects, the earlier Orkhon Turkic and the later Old Uyghur. There is a difference of opinion among linguists with regard to the Karakhanid language, some classify it as another dialect of East Old Turkic, while others prefer to include Karakhanid among Middle Turkic languages; nonetheless, Karakhanid is very close to Old Uyghur. East Old Turkic and West Old Turkic together comprise the Old Turkic proper, though West Old Turkic is generally unattested and is mostly reconstructed through words loaned through Hungarian. East Old Turkic is the oldest attested member of the Siberian Turkic branch of Turkic languages, and several of its now-archaic grammatical as well as lexical features are extant in the modern Yellow Uyghur, Lop Nur Uyghur and Khalaj ; Khalaj, for instance, has (surprisingly) retained a considerable number of archaic Old Turkic words despite forming a language island within Central Iran and being heavily influenced by Persian. Old Uyghur is not a direct ancestor of the modern Uyghur language, but rather the Western Yugur language; the contemporaneous ancestor of Modern Uyghur was the Chagatai literary language.

An elteber was a client king of an autonomous but tributary tribe or polity in the hierarchy of the Turkic khaganates including Khazar Khaganate.

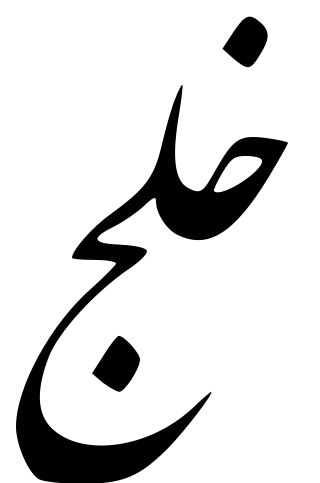

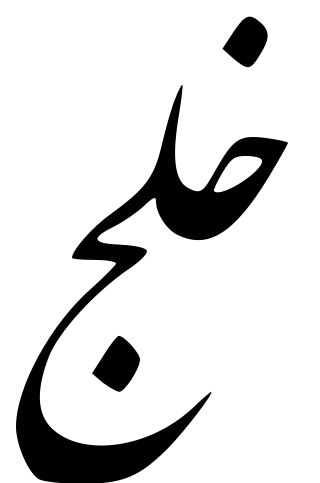

Khalaj is a Turkic language spoken in Iran. Although it contains many old Turkic elements, it has become widely Persianized. Khalaj has about 150 words of uncertain origin.

The Oghuric, Onoguric or Oguric languages are a branch of the Turkic language family. The only extant member of the group is the Chuvash language. The first to branch off from the Turkic family, the Oghuric languages show significant divergence from other Turkic languages, which all share a later common ancestor. Languages from this family were spoken in some nomadic tribal confederations, such as those of the Onogurs or Ogurs, Bulgars and Khazars.

Anna Vladimirovna Dybo is a Russian linguist, member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, and co-author of the Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages (2003), which encompasses some 3,000 Proto-Altaic stems.

Yakutyə-KOOT, also known as Yakutian, Sakha, Saqa or Saxa, is a Turkic language belonging to Siberian Turkic branch and spoken by around 450,000 native speakers, primarily the ethnic Yakuts and one of the official languages of Sakha (Yakutia), a federal republic in the Russian Federation.

This article covers the phonology of the Uyghur language. Uyghur, a Turkic language spoken primarily in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region features both vowel harmony and vowel reduction.

Proto-Slavic is the unattested, reconstructed proto-language of all Slavic languages. It represents Slavic speech approximately from the 2nd millennium BC through the 6th century AD. As with most other proto-languages, no attested writings have been found; scholars have reconstructed the language by applying the comparative method to all the attested Slavic languages and by taking into account other Indo-European languages.

The Etymological Dictionary of the Altaic Languages is a comparative and etymological dictionary of the hypothetical Altaic language family. It was written by linguists Sergei Starostin, Anna Dybo, and Oleg Mudrak, and was published in Leiden in 2003 by Brill Publishers. It contains 3 volumes, and is a part of the Handbook of Oriental Studies: Section 8, Uralic and Central Asian Studies; no. 8.