The cytoskeleton is a complex, dynamic network of interlinking protein filaments present in the cytoplasm of all cells, including those of bacteria and archaea. In eukaryotes, it extends from the cell nucleus to the cell membrane and is composed of similar proteins in the various organisms. It is composed of three main components: microfilaments, intermediate filaments, and microtubules, and these are all capable of rapid growth or disassembly depending on the cell's requirements.

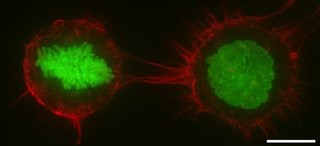

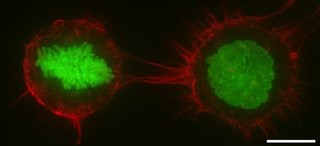

Cytokinesis is the part of the cell division process and part of mitosis during which the cytoplasm of a single eukaryotic cell divides into two daughter cells. Cytoplasmic division begins during or after the late stages of nuclear division in mitosis and meiosis. During cytokinesis the spindle apparatus partitions and transports duplicated chromatids into the cytoplasm of the separating daughter cells. It thereby ensures that chromosome number and complement are maintained from one generation to the next and that, except in special cases, the daughter cells will be functional copies of the parent cell. After the completion of the telophase and cytokinesis, each daughter cell enters the interphase of the cell cycle.

Saccharomyces cerevisiae is a species of yeast. The species has been instrumental in winemaking, baking, and brewing since ancient times. It is believed to have been originally isolated from the skin of grapes. It is one of the most intensively studied eukaryotic model organisms in molecular and cell biology, much like Escherichia coli as the model bacterium. It is the microorganism behind the most common type of fermentation. S. cerevisiae cells are round to ovoid, 5–10 μm in diameter. It reproduces by budding.

FtsZ is a protein encoded by the ftsZ gene that assembles into a ring at the future site of bacterial cell division. FtsZ is a prokaryotic homologue of the eukaryotic protein tubulin. The initials FtsZ mean "Filamenting temperature-sensitive mutant Z." The hypothesis was that cell division mutants of E. coli would grow as filaments due to the inability of the daughter cells to separate from one another. FtsZ is found in almost all bacteria, many archaea, all chloroplasts and some mitochondria, where it is essential for cell division. FtsZ assembles the cytoskeletal scaffold of the Z ring that, along with additional proteins, constricts to divide the cell in two.

The exocyst is an octameric protein complex involved in vesicle trafficking, specifically the tethering and spatial targeting of post-Golgi vesicles to the plasma membrane prior to vesicle fusion. It is implicated in a number of cell processes, including exocytosis, cell migration, and growth.

The cell cortex, also known as the actin cortex, cortical cytoskeleton or actomyosin cortex, is a specialized layer of cytoplasmic proteins on the inner face of the cell membrane. It functions as a modulator of membrane behavior and cell surface properties. In most eukaryotic cells lacking a cell wall, the cortex is an actin-rich network consisting of F-actin filaments, myosin motors, and actin-binding proteins. The actomyosin cortex is attached to the cell membrane via membrane-anchoring proteins called ERM proteins that plays a central role in cell shape control. The protein constituents of the cortex undergo rapid turnover, making the cortex both mechanically rigid and highly plastic, two properties essential to its function. In most cases, the cortex is in the range of 100 to 1000 nanometers thick.

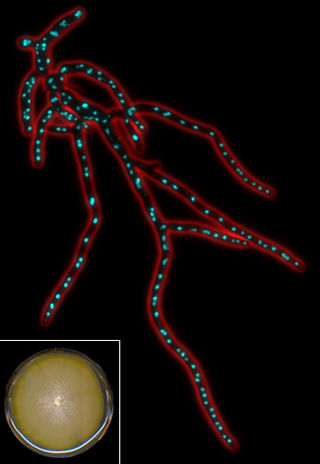

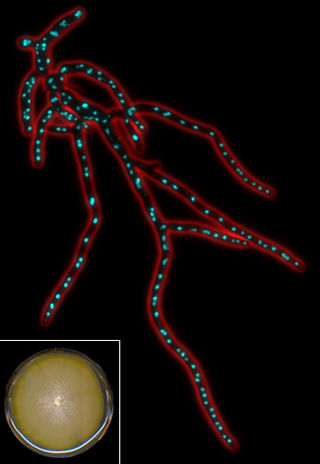

Eremothecium gossypii (also known as Ashbya gossypii) is a filamentous fungus or mold closely related to yeast, but growing exclusively in a filamentous way. It was originally isolated from cotton as a pathogen causing stigmatomycosis by Ashby and Nowell in 1926. This disease affects the development of hair cells in cotton bolls and can be transmitted to citrus fruits, which thereupon dry out and collapse (dry rot disease). In the first part of the 20th century, E. gossypii and two other fungi causing stigmatomycosis (Eremothecium coryli, Aureobasidium pullulans) made it virtually impossible to grow cotton in certain regions of the subtropics, causing severe economical losses. Control of the spore-transmitting insects - cotton stainer (Dysdercus suturellus) and Antestiopsis (antestia bugs) - permitted full eradication of infections. E. gossypii was recognized as a natural overproducer of riboflavin (vitamin B2), which protects its spores against ultraviolet light. This made it an interesting organism for industries, where genetically modified strains are still used to produce this vitamin.

The Rho family of GTPases is a family of small signaling G proteins, and is a subfamily of the Ras superfamily. The members of the Rho GTPase family have been shown to regulate many aspects of intracellular actin dynamics, and are found in all eukaryotic kingdoms, including yeasts and some plants. Three members of the family have been studied in detail: Cdc42, Rac1, and RhoA. All G proteins are "molecular switches", and Rho proteins play a role in organelle development, cytoskeletal dynamics, cell movement, and other common cellular functions.

The prokaryotic cytoskeleton is the collective name for all structural filaments in prokaryotes. It was once thought that prokaryotic cells did not possess cytoskeletons, but advances in visualization technology and structure determination led to the discovery of filaments in these cells in the early 1990s. Not only have analogues for all major cytoskeletal proteins in eukaryotes been found in prokaryotes, cytoskeletal proteins with no known eukaryotic homologues have also been discovered. Cytoskeletal elements play essential roles in cell division, protection, shape determination, and polarity determination in various prokaryotes.

Septin 2, also known as SEPT2, is a protein which in humans is encoded by the SEPT2 gene.

Septin-6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SEPT6 gene.

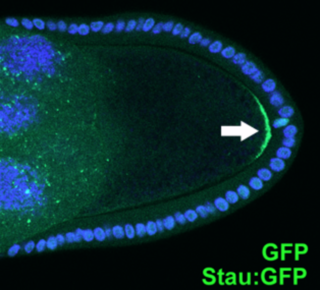

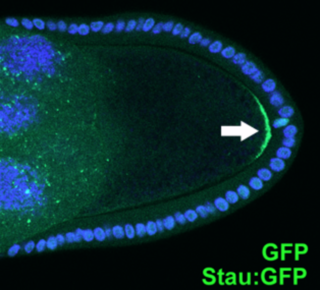

Anillin is a conserved protein implicated in cytoskeletal dynamics during cellularization and cytokinesis. The ANLN gene in humans and the scraps gene in Drosophila encode Anillin. In 1989, anillin was first isolated in embryos of Drosophila melanogaster. It was identified as an F-actin binding protein. Six years later, the anillin gene was cloned from cDNA originating from a Drosophila ovary. Staining with anti-anillin antibody showed the anillin localizes to the nucleus during interphase and to the contractile ring during cytokinesis. These observations agree with further research that found anillin in high concentrations near the cleavage furrow coinciding with RhoA, a key regulator of contractile ring formation.

Septin-7 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the SEPT7 gene.

The endosomal sorting complexes required for transport (ESCRT) machinery is made up of cytosolic protein complexes, known as ESCRT-0, ESCRT-I, ESCRT-II, and ESCRT-III. Together with a number of accessory proteins, these ESCRT complexes enable a unique mode of membrane remodeling that results in membranes bending/budding away from the cytoplasm. These ESCRT components have been isolated and studied in a number of organisms including yeast and humans. A eukaryotic signature protein, the machinery is found in all eukaryotes and some archaea.

Cell polarity refers to spatial differences in shape, structure, and function within a cell. Almost all cell types exhibit some form of polarity, which enables them to carry out specialized functions. Classical examples of polarized cells are described below, including epithelial cells with apical-basal polarity, neurons in which signals propagate in one direction from dendrites to axons, and migrating cells. Furthermore, cell polarity is important during many types of asymmetric cell division to set up functional asymmetries between daughter cells.

Cdc14 and Cdc14 are a gene and its protein product respectively. Cdc14 is found in most of the eukaryotes. Cdc14 was defined by Hartwell in his famous screen for loci that control the cell cycle of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cdc14 was later shown to encode a protein phosphatase. Cdc14 is dual-specificity, which means it has serine/threonine and tyrosine-directed activity. A preference for serines next to proline is reported. Many early studies, especially in the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, demonstrated that the protein plays a key role in regulating late mitotic processes. However, more recent work in a range of systems suggests that its cellular function is more complex.

In molecular biology, the cyclase-associated protein family (CAP) is a family of highly conserved actin-binding proteins present in a wide range of organisms including yeast, flies, plants, and mammals. CAPs are multifunctional proteins that contain several structural domains. CAP is involved in species-specific signalling pathways. In Drosophila, CAP functions in Hedgehog-mediated eye development and in establishing oocyte polarity. In Dictyostelium discoideum, CAP is involved in microfilament reorganisation near the plasma membrane in a PIP2-regulated manner and is required to perpetuate the cAMP relay signal to organise fruitbody formation. In plants, CAP is involved in plant signalling pathways required for co-ordinated organ expansion. In yeast, CAP is involved in adenylate cyclase activation, as well as in vesicle trafficking and endocytosis. In both yeast and mammals, CAPs appear to be involved in recycling G-actin monomers from ADF/cofilins for subsequent rounds of filament assembly. In mammals, there are two different CAPs that share 64% amino acid identity.

Rong Li is the Director of Mechanobiology Institute, a Singapore Research Center of Excellence, at the National University of Singapore. She is a Distinguished Professor at the National University of Singapore's Department of Biological Sciences and Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Cell Biology and Chemical & Biomolecular Engineering at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and Whiting School of Engineering. She previously served as Director of Center for Cell Dynamics in the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine’s Institute for Basic Biomedical Sciences. She is a leader in understanding cellular asymmetry, division and evolution, and specifically, in how eukaryotic cells establish their distinct morphology and organization in order to carry out their specialized functions.

Amy S. Gladfelter is an American quantitative cell biologist who is interested in understanding fundamental mechanisms of cell organization. She is a Professor of Biology and the Associate Chair for Diversity Initiatives at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where she investigates cell cycle control and the septin cytoskeleton. She is also affiliated with the Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center and is a fellow of the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA.

In molecular biology, an actomyosin ring or contractile ring, is a prominent structure during cytokinesis. It forms perpendicular to the axis of the spindle apparatus towards the end of telophase, in which sister chromatids are identically separated at the opposite sides of the spindle forming nuclei. The actomyosin ring follows an orderly sequence of events: identification of the active division site, formation of the ring, constriction of the ring, and disassembly of the ring. It is composed of actin and myosin II bundles, thus the term actomyosin. The actomyosin ring operates in contractile motion, although the mechanism on how or what triggers the constriction is still an evolving topic. Other cytoskeletal proteins are also involved in maintaining the stability of the ring and driving its constriction. Apart from cytokinesis, in which the ring constricts as the cells divide, actomyosin ring constriction has also been found to activate during wound closure. During this process, actin filaments are degraded, preserving the thickness of the ring. After cytokinesis is complete, one of the two daughter cells inherits a remnant known as the midbody ring.