Laura Jane Addams was an American settlement activist, reformer, social worker, sociologist, public administrator, philosopher, and author. She was an important leader in the history of social work and women's suffrage in the United States. Addams co-founded Chicago's Hull House, one of America's most famous settlement houses, providing extensive social services to poor, largely immigrant families. In 1910, Addams was awarded an honorary Master of Arts degree from Yale University, becoming the first woman to receive an honorary degree from the school. In 1920, she was a co-founder of the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU).

Hull House was a settlement house in Chicago, Illinois, that was co-founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Gates Starr. Located on the Near West Side of Chicago, Hull House, named after the original house's first owner Charles Jerald Hull, opened to serve recently arrived European immigrants. By 1911, Hull House had expanded to 13 buildings. In 1912, the Hull House complex was completed with the addition of a summer camp, the Bowen Country Club. With its innovative social, educational, and artistic programs, Hull House became the standard bearer for the movement; by 1920, it grew to approximately 500 settlement houses nationally.

Women's suffrage is the right of women to vote in elections. In the beginning of the 18th century, some people sought to change voting laws to allow women to vote. Liberal political parties would go on to grant women the right to vote, increasing the number of those parties' potential constituencies. National and international organizations formed to coordinate efforts towards women voting, especially the International Woman Suffrage Alliance.

The Progressive Era (1896–1917) was a period of widespread social activism and political reform across the United States focused on defeating corruption, monopoly, waste, and inefficiency. The main themes ended during American involvement in World War I (1917–1918) while the waste and efficiency elements continued into the 1920s. Progressives sought to address the problems caused by rapid industrialization, urbanization, immigration, and political corruption; and by the enormous concentration of industrial ownership in monopolies. They were alarmed by the spread of slums, poverty, and the exploitation of labor. Multiple overlapping progressive movements fought perceived social, political and economic ills by advancing democracy, scientific methods, professionalism and efficiency; regulating businesses, protecting the natural environment, and improving working conditions in factories and living conditions of the urban poor. Spreading the message of reform through mass-circulation newspapers and magazines by "probing the dark corners of American life" were investigative journalists known as "muckrakers". The main advocates of progressivism were often middle-class social reformers.

Public administration or public policy and administration is the implementation of public policy, administration of government establishment, and management of non-profit establishment. It is also a sub-field of political science taught in public policy schools that studies this implementation and prepares civil servants in administrative positions primarily for work in the public sector. People with public administration knowledge may also be employed in a voluntary sector, or some other industries in the private sector dealing with government relations, regulatory affairs, legislative assistance, corporate social responsibilities (CSR), environmental, social, governance (ESG), public procurement (PP), public-private partnerships (P3), and business-to-government marketing/sales (B2G), as well as those working at think tanks, non-profit organizations, consulting firms, trade associations, or in other positions that use similar skills found in public administration.

Julia Clifford Lathrop was an American social reformer in the area of education, social policy, and children's welfare. As director of the United States Children's Bureau from 1912 to 1922, she was the first woman ever to head a United States federal bureau.

Housekeeping is the management and routine support activities of running and maintaining an organized physical institution occupied or used by people, like a house, ship, hospital or factory, such as cleaning, tidying/organizing, cooking, shopping, and bill payment. These tasks may be performed by members of the household, or by persons hired for the purpose. This is a more broad role than a cleaner, who is focused only on the cleaning aspect. The term is also used to refer to the money allocated for such use. By extension, it may also refer to an office or a corporation, as well as the maintenance of computer storage systems.

Progressivism in the United States is a political philosophy and reform movement. Into the 21st century, it advocates policies that are generally considered social democratic and part of the American Left. It has also expressed itself with right-wing politics, such as New Nationalism and progressive conservatism. It reached its height early in the 20th century. Middle/working class and reformist in nature, it arose as a response to the vast changes brought by modernization, such as the growth of large corporations, pollution, and corruption in American politics. Historian Alonzo Hamby describes American progressivism as a "political movement that addresses ideas, impulses, and issues stemming from modernization of American society. Emerging at the end of the nineteenth century, it established much of the tone of American politics throughout the first half of the century."

Manual scavenging is a term used mainly in India for "manually cleaning, carrying, disposing of, or otherwise handling, human excreta in an insanitary latrine or in an open drain or sewer or in a septic tank or a pit". Manual scavengers usually use hand tools such as buckets, brooms and shovels. The workers have to move the excreta, using brooms and tin plates, into baskets, which they carry to disposal locations sometimes several kilometers away. The practice of employing human labour for cleaning of sewers and septic tanks is also prevalent in Bangladesh and Pakistan. These sanitation workers, called "manual scavengers", rarely have any personal protective equipment. The work is regarded as a dehumanizing practice.

The General Federation of Women's Clubs (GFWC), founded in 1890 during the Progressive Movement, is a federation of over 3,000 women's clubs in the United States which promote civic improvements through volunteer service. Many of its activities and service projects are done independently by local clubs through their communities or GFWC's national partnerships. GFWC maintains nearly 70,000 members throughout the United States and internationally. GFWC remains one of the world's largest and oldest nonpartisan, nondenominational, women's volunteer service organizations. The GFWC headquarters is located in Washington, D.C.

Ellen Gates Starr was an American social reformer and activist. With Jane Addams, she founded Chicago's Hull House, an adult education center, in 1889; the settlement house expanded to 13 buildings in the neighborhood.

Rheta Louise Childe Dorr (1868–1948) was an American journalist, suffragist newspaper editor, writer, and political activist. Dorr is best remembered as one of the leading female muckraking journalists of the Progressive era and as the first editor of the influential newspaper, The Suffragist.

The Woman's Peace Party (WPP) was an American pacifist and feminist organization formally established in January 1915 in response to World War I. The organization is remembered as the first American peace organization to make use of direct action tactics such as public demonstration. The Woman's Peace Party became the American section of an international organization known as the International Committee of Women for Permanent Peace later in 1915, a group which later changed its name to the Women's International League for Peace and Freedom.

A sanitation worker is a person responsible for cleaning, maintaining, operating, or emptying the equipment or technology at any step of the sanitation chain. This is the definition used in the narrower sense within the WASH sector. More broadly speaking, sanitation workers may also be involved in cleaning streets, parks, public spaces, sewers, stormwater drains, and public toilets. Another definition is: "The moment an individual’s waste is outsourced to another, it becomes sanitation work." Some organizations use the term specifically for municipal solid waste collectors, whereas others exclude the workers involved in management of solid waste sector from its definition.

Social feminism is a feminist movement that advocates for social rights and special accommodations for women. It was first used to describe members of the women's suffrage movement in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries who were concerned with social problems that affected women and children. They saw obtaining the vote mainly as a means to achieve their reform goals rather than a primary goal in itself. After women gained the right to vote, social feminism continued in the form of labor feminists who advocated for protectionist legislation and special benefits for women. The term is widely used, although some historians have questioned its validity.

Caroline Bartlett Crane was an American Unitarian minister, suffragist, civic reformer, educator and journalist. She was known as "America's housekeeper" for her efforts to improve urban sanitation.

Swachh Bharat Mission, Swachh Bharat Abhiyan, or Clean India Mission is a country-wide campaign initiated by the Government of India on 2 October 2014 to eliminate open defecation and improve solid waste management and to create Open Defecation Free (ODF) villages. The program also aims to increase awareness of menstrual health management. It is a restructured version of the Nirmal Bharat Abhiyan which was launched by Congress in 2009 that failed to achieve its intended targets due to rampant corruption and indecisive leadership.

The Nineteenth Century Club is a historic philanthropic and cultural women's club based in Memphis, Tennessee. The Nineteenth Century Club adopted the idea that the community was an extended "household" that would benefit from the "gentler spirit" and "uplifting influence" of women, and shifted towards civic reform. The club primarily focused on the needs of women and children, addressing public problems such as sanitation, health, education, employment, and labor conditions.

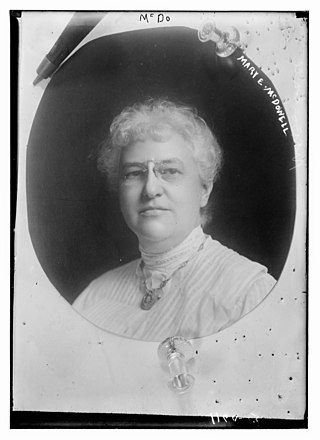

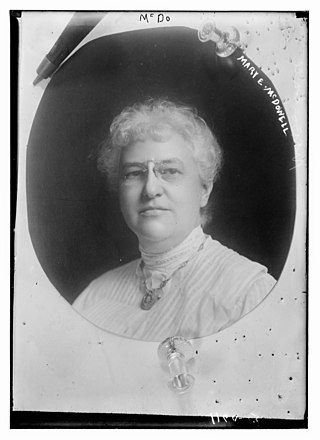

Mary Eliza McDowell was an American social reformer and prominent figure in the Chicago Settlement movement.

The woman's club movement was a social movement that took place throughout the United States that established the idea that women had a moral duty and responsibility to transform public policy. While women's organizations had always been a part of United States history, it was not until the Progressive era that it came to be considered a movement. The first wave of the club movement during the progressive era was started by white, middle-class, Protestant women, and a second phase was led by African-American women.