In chemical analysis, chromatography is a laboratory technique for the separation of a mixture into its components. The mixture is dissolved in a fluid solvent called the mobile phase, which carries it through a system on which a material called the stationary phase is fixed. Because the different constituents of the mixture tend to have different affinities for the stationary phase and are retained for different lengths of time depending on their interactions with its surface sites, the constituents travel at different apparent velocities in the mobile fluid, causing them to separate. The separation is based on the differential partitioning between the mobile and the stationary phases. Subtle differences in a compound's partition coefficient result in differential retention on the stationary phase and thus affect the separation.

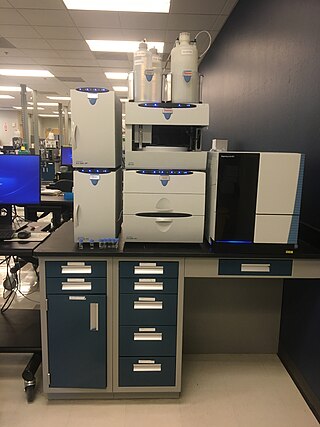

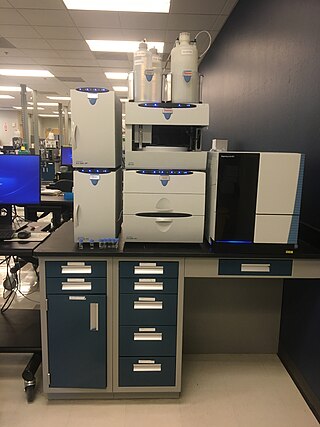

High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC), formerly referred to as high-pressure liquid chromatography, is a technique in analytical chemistry used to separate, identify, and quantify specific components in mixtures. The mixtures can originate from food, chemicals, pharmaceuticals, biological, environmental and agriculture, etc, which have been dissolved into liquid solutions.

Gas chromatography (GC) is a common type of chromatography used in analytical chemistry for separating and analyzing compounds that can be vaporized without decomposition. Typical uses of GC include testing the purity of a particular substance, or separating the different components of a mixture. In preparative chromatography, GC can be used to prepare pure compounds from a mixture.

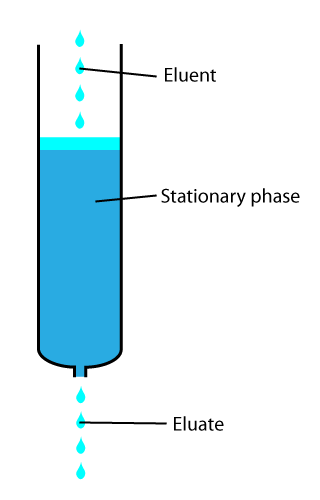

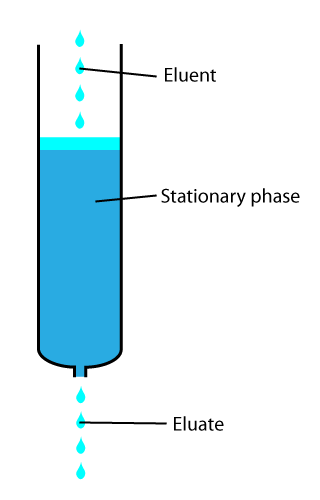

Column chromatography in chemistry is a chromatography method used to isolate a single chemical compound from a mixture. Chromatography is able to separate substances based on differential adsorption of compounds to the adsorbent; compounds move through the column at different rates, allowing them to be separated into fractions. The technique is widely applicable, as many different adsorbents can be used with a wide range of solvents. The technique can be used on scales from micrograms up to kilograms. The main advantage of column chromatography is the relatively low cost and disposability of the stationary phase used in the process. The latter prevents cross-contamination and stationary phase degradation due to recycling. Column chromatography can be done using gravity to move the solvent, or using compressed gas to push the solvent through the column.

Ion chromatography is a form of chromatography that separates ions and ionizable polar molecules based on their affinity to the ion exchanger. It works on almost any kind of charged molecule—including small inorganic anions, large proteins, small nucleotides, and amino acids. However, ion chromatography must be done in conditions that are one pH unit away from the isoelectric point of a protein.

Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) is a chromatography technique that separates components in non-volatile mixtures.

Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) is an analytical chemistry technique that combines the physical separation capabilities of liquid chromatography with the mass analysis capabilities of mass spectrometry (MS). Coupled chromatography – MS systems are popular in chemical analysis because the individual capabilities of each technique are enhanced synergistically. While liquid chromatography separates mixtures with multiple components, mass spectrometry provides spectral information that may help to identify each separated component. MS is not only sensitive, but provides selective detection, relieving the need for complete chromatographic separation. LC–MS is also appropriate for metabolomics because of its good coverage of a wide range of chemicals. This tandem technique can be used to analyze biochemical, organic, and inorganic compounds commonly found in complex samples of environmental and biological origin. Therefore, LC–MS may be applied in a wide range of sectors including biotechnology, environment monitoring, food processing, and pharmaceutical, agrochemical, and cosmetic industries. Since the early 2000s, LC–MS has also begun to be used in clinical applications.

Liquid–liquid extraction (LLE), also known as solvent extraction and partitioning, is a method to separate compounds or metal complexes, based on their relative solubilities in two different immiscible liquids, usually water (polar) and an organic solvent (non-polar). There is a net transfer of one or more species from one liquid into another liquid phase, generally from aqueous to organic. The transfer is driven by chemical potential, i.e. once the transfer is complete, the overall system of chemical components that make up the solutes and the solvents are in a more stable configuration. The solvent that is enriched in solute(s) is called extract. The feed solution that is depleted in solute(s) is called the raffinate. LLE is a basic technique in chemical laboratories, where it is performed using a variety of apparatus, from separatory funnels to countercurrent distribution equipment called as mixer settlers. This type of process is commonly performed after a chemical reaction as part of the work-up, often including an acidic work-up.

Solid phase microextraction, or SPME, is a solid phase extraction sampling technique that involves the use of a fiber coated with an extracting phase, that can be a liquid (polymer) or a solid (sorbent), which extracts different kinds of analytes from different kinds of media, that can be in liquid or gas phase. The quantity of analyte extracted by the fibre is proportional to its concentration in the sample as long as equilibrium is reached or, in case of short time pre-equilibrium, with help of convection or agitation.

Reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RP-LC) is a mode of liquid chromatography in which non-polar stationary phase and polar mobile phases are used for the separation of organic compounds. The vast majority of separations and analyses using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) in recent years are done using the reversed phase mode. In the reversed phase mode, the sample components are retained in the system the more hydrophobic they are.

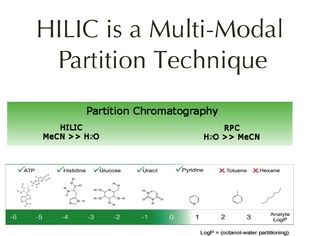

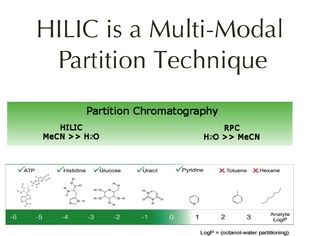

Hydrophilic interaction chromatography is a variant of normal phase liquid chromatography that partly overlaps with other chromatographic applications such as ion chromatography and reversed phase liquid chromatography. HILIC uses hydrophilic stationary phases with reversed-phase type eluents. The name was suggested by Andrew Alpert in his 1990 paper on the subject. He described the chromatographic mechanism for it as liquid-liquid partition chromatography where analytes elute in order of increasing polarity, a conclusion supported by a review and re-evaluation of published data.

Supercritical fluid chromatography (SFC) is a form of normal phase chromatography that uses a supercritical fluid such as carbon dioxide as the mobile phase. It is used for the analysis and purification of low to moderate molecular weight, thermally labile molecules and can also be used for the separation of chiral compounds. Principles are similar to those of high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC); however, SFC typically utilizes carbon dioxide as the mobile phase. Therefore, the entire chromatographic flow path must be pressurized. Because the supercritical phase represents a state whereby bulk liquid and gas properties converge, supercritical fluid chromatography is sometimes called convergence chromatography. The idea of liquid and gas properties convergence was first envisioned by Giddings.

Aqueous normal-phase chromatography (ANP) is a chromatographic technique that involves the mobile phase compositions and polarities between reversed-phase chromatography (RP) and normal-phase chromatography (NP), while the stationary phases are polar.

Acid–base extraction is a subclass of liquid–liquid extractions and involves the separation of chemical species from other acidic or basic compounds. It is typically performed during the work-up step following a chemical synthesis to purify crude compounds and results in the product being largely free of acidic or basic impurities. A separatory funnel is commonly used to perform an acid-base extraction.

In analytical and organic chemistry, elution is the process of extracting one material from another by washing with a solvent; as in washing of loaded ion-exchange resins to remove captured ions.

Two-dimensional chromatography is a type of chromatographic technique in which the injected sample is separated by passing through two different separation stages. Two different chromatographic columns are connected in sequence, and the effluent from the first system is transferred onto the second column. Typically the second column has a different separation mechanism, so that bands that are poorly resolved from the first column may be completely separated in the second column. Alternately, the two columns might run at different temperatures. During the second stage of separation the rate at which the separation occurs must be faster than the first stage, since there is still only a single detector. The plane surface is amenable to sequential development in two directions using two different solvents.

Countercurrent chromatography is a form of liquid–liquid chromatography that uses a liquid stationary phase that is held in place by inertia of the molecules composing the stationary phase accelerating toward the center of a centrifuge due to centripetal force and is used to separate, identify, and quantify the chemical components of a mixture. In its broadest sense, countercurrent chromatography encompasses a collection of related liquid chromatography techniques that employ two immiscible liquid phases without a solid support. The two liquid phases come in contact with each other as at least one phase is pumped through a column, a hollow tube or a series of chambers connected with channels, which contains both phases. The resulting dynamic mixing and settling action allows the components to be separated by their respective solubilities in the two phases. A wide variety of two-phase solvent systems consisting of at least two immiscible liquids may be employed to provide the proper selectivity for the desired separation.

Analytical thermal desorption, known within the analytical chemistry community simply as "thermal desorption" (TD), is a technique that concentrates volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in gas streams prior to injection into a gas chromatograph (GC). It can be used to lower the detection limits of GC methods, and can improve chromatographic performance by reducing peak widths.

Thermoresponsive polymers can be used as stationary phase in liquid chromatography. Here, the polarity of the stationary phase can be varied by temperature changes, altering the power of separation without changing the column or solvent composition. Thermally related benefits of gas chromatography can now be applied to classes of compounds that are restricted to liquid chromatography due to their thermolability. In place of solvent gradient elution, thermoresponsive polymers allow the use of temperature gradients under purely aqueous isocratic conditions. The versatility of the system is controlled not only through changing temperature, but through the addition of modifying moieties that allow for a choice of enhanced hydrophobic interaction, or by introducing the prospect of electrostatic interaction. These developments have already introduced major improvements to the fields of hydrophobic interaction chromatography, size exclusion chromatography, ion exchange chromatography, and affinity chromatography separations as well as pseudo-solid phase extractions.

Centrifugal partition chromatography is a special chromatographic technique where both stationary and mobile phase are liquid, and the stationary phase is immobilized by a strong centrifugal force. Centrifugal partition chromatography consists of a series-connected network of extraction cells, which operates as elemental extractors, and the efficiency is guaranteed by the cascade.