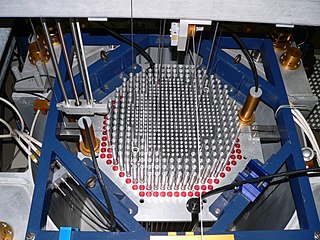

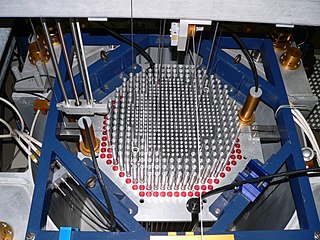

A nuclear reactor is a device used to initiate and control a fission nuclear chain reaction or nuclear fusion reactions. Nuclear reactors are used at nuclear power plants for electricity generation and in nuclear marine propulsion. Heat from nuclear fission is passed to a working fluid, which in turn runs through steam turbines. These either drive a ship's propellers or turn electrical generators' shafts. Nuclear generated steam in principle can be used for industrial process heat or for district heating. Some reactors are used to produce isotopes for medical and industrial use, or for production of weapons-grade plutonium. As of 2022, the International Atomic Energy Agency reports there are 422 nuclear power reactors and 223 nuclear research reactors in operation around the world.

Uranium is a chemical element; it has symbol U and atomic number 92. It is a silvery-grey metal in the actinide series of the periodic table. A uranium atom has 92 protons and 92 electrons, of which 6 are valence electrons. Uranium radioactively decays by emitting an alpha particle. The half-life of this decay varies between 159,200 and 4.5 billion years for different isotopes, making them useful for dating the age of the Earth. The most common isotopes in natural uranium are uranium-238 and uranium-235. Uranium has the highest atomic weight of the primordially occurring elements. Its density is about 70% higher than that of lead and slightly lower than that of gold or tungsten. It occurs naturally in low concentrations of a few parts per million in soil, rock and water, and is commercially extracted from uranium-bearing minerals such as uraninite.

Isotope separation is the process of concentrating specific isotopes of a chemical element by removing other isotopes. The use of the nuclides produced is varied. The largest variety is used in research. By tonnage, separating natural uranium into enriched uranium and depleted uranium is the largest application. In the following text, mainly uranium enrichment is considered. This process is crucial in the manufacture of uranium fuel for nuclear power plants, and is also required for the creation of uranium-based nuclear weapons. Plutonium-based weapons use plutonium produced in a nuclear reactor, which must be operated in such a way as to produce plutonium already of suitable isotopic mix or grade.

Enriched uranium is a type of uranium in which the percent composition of uranium-235 has been increased through the process of isotope separation. Naturally-occurring uranium is composed of three major isotopes: uranium-238, uranium-235, and uranium-234. 235U is the only nuclide existing in nature that is fissile with thermal neutrons.

In nuclear engineering, fissile material is material that can undergo nuclear fission when struck by a neutron of low energy. A self-sustaining thermal chain reaction can only be achieved with fissile material. The predominant neutron energy in a system may be typified by either slow neutrons or fast neutrons. Fissile material can be used to fuel thermal-neutron reactors, fast-neutron reactors and nuclear explosives.

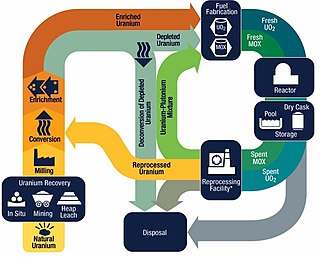

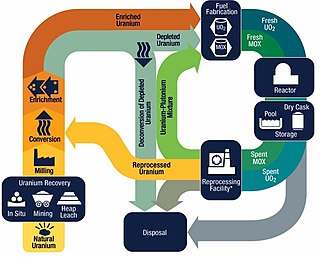

The nuclear fuel cycle, also called nuclear fuel chain, is the progression of nuclear fuel through a series of differing stages. It consists of steps in the front end, which are the preparation of the fuel, steps in the service period in which the fuel is used during reactor operation, and steps in the back end, which are necessary to safely manage, contain, and either reprocess or dispose of spent nuclear fuel. If spent fuel is not reprocessed, the fuel cycle is referred to as an open fuel cycle ; if the spent fuel is reprocessed, it is referred to as a closed fuel cycle.

Mixed oxide fuel, commonly referred to as MOX fuel, is nuclear fuel that contains more than one oxide of fissile material, usually consisting of plutonium blended with natural uranium, reprocessed uranium, or depleted uranium. MOX fuel is an alternative to the low-enriched uranium fuel used in the light-water reactors that predominate nuclear power generation.

The Baghdad Nuclear Research Facility adjacent to the Tuwaitha "Yellow Cake Factory" or Tuwaitha Nuclear Research Center contains the remains of nuclear reactors bombed by Iran in 1980, Israel in 1981 and the United States in 1991. It was used as a storage facility for spent reactor fuel and industrial and medical wastes. The radioactive material would not be useful for a fission bomb, but could be used in a dirty bomb. Following the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the facility was heavily looted by hundreds of Iraqis, though it is unclear what was taken.

A breeder reactor is a nuclear reactor that generates more fissile material than it consumes. These reactors can be fueled with more-commonly available isotopes of uranium and thorium, such as uranium-238 and thorium-232, as opposed to the rare uranium-235 which is used in conventional reactors. These materials are called fertile materials since they can be bred into fuel by these breeder reactors.

Uranium-238 is the most common isotope of uranium found in nature, with a relative abundance of 99%. Unlike uranium-235, it is non-fissile, which means it cannot sustain a chain reaction in a thermal-neutron reactor. However, it is fissionable by fast neutrons, and is fertile, meaning it can be transmuted to fissile plutonium-239. 238U cannot support a chain reaction because inelastic scattering reduces neutron energy below the range where fast fission of one or more next-generation nuclei is probable. Doppler broadening of 238U's neutron absorption resonances, increasing absorption as fuel temperature increases, is also an essential negative feedback mechanism for reactor control.

A fast-neutron reactor (FNR) or fast-spectrum reactor or simply a fast reactor is a category of nuclear reactor in which the fission chain reaction is sustained by fast neutrons, as opposed to slow thermal neutrons used in thermal-neutron reactors. Such a fast reactor needs no neutron moderator, but requires fuel that is relatively rich in fissile material when compared to that required for a thermal-neutron reactor. Around 20 land based fast reactors have been built, accumulating over 400 reactor years of operation globally. The largest of this was the Superphénix Sodium cooled fast reactor in France that was designed to deliver 1,242 MWe. Fast reactors have been intensely studied since the 1950s, as they provide certain advantages over the existing fleet of water cooled and water moderated reactors. These are:

Nuclear material refers to the metals uranium, plutonium, and thorium, in any form, according to the IAEA. This is differentiated further into "source material", consisting of natural and depleted uranium, and "special fissionable material", consisting of enriched uranium (U-235), uranium-233, and plutonium-239. Uranium ore concentrates are considered to be a "source material", although these are not subject to safeguards under the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty.

Fertile material is a material that, although not fissile itself, can be converted into a fissile material by neutron absorption.

Plutonium-239 is an isotope of plutonium. Plutonium-239 is the primary fissile isotope used for the production of nuclear weapons, although uranium-235 is also used for that purpose. Plutonium-239 is also one of the three main isotopes demonstrated usable as fuel in thermal spectrum nuclear reactors, along with uranium-235 and uranium-233. Plutonium-239 has a half-life of 24,110 years.

Uranium (92U) is a naturally occurring radioactive element that has no stable isotope. It has two primordial isotopes, uranium-238 and uranium-235, that have long half-lives and are found in appreciable quantity in the Earth's crust. The decay product uranium-234 is also found. Other isotopes such as uranium-233 have been produced in breeder reactors. In addition to isotopes found in nature or nuclear reactors, many isotopes with far shorter half-lives have been produced, ranging from 214U to 242U. The standard atomic weight of natural uranium is 238.02891(3).

Plutonium (94Pu) is an artificial element, except for trace quantities resulting from neutron capture by uranium, and thus a standard atomic weight cannot be given. Like all artificial elements, it has no stable isotopes. It was synthesized long before being found in nature, the first isotope synthesized being plutonium-238 in 1940. Twenty plutonium radioisotopes have been characterized. The most stable are plutonium-244 with a half-life of 80.8 million years, plutonium-242 with a half-life of 373,300 years, and plutonium-239 with a half-life of 24,110 years. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are less than 7,000 years. This element also has eight meta states; all have half-lives of less than one second.

The thorium fuel cycle is a nuclear fuel cycle that uses an isotope of thorium, 232

Th

, as the fertile material. In the reactor, 232

Th

is transmuted into the fissile artificial uranium isotope 233

U

which is the nuclear fuel. Unlike natural uranium, natural thorium contains only trace amounts of fissile material, which are insufficient to initiate a nuclear chain reaction. Additional fissile material or another neutron source is necessary to initiate the fuel cycle. In a thorium-fuelled reactor, 232

Th

absorbs neutrons to produce 233

U

. This parallels the process in uranium breeder reactors whereby fertile 238

U

absorbs neutrons to form fissile 239

Pu

. Depending on the design of the reactor and fuel cycle, the generated 233

U

either fissions in situ or is chemically separated from the used nuclear fuel and formed into new nuclear fuel.

Weapons-grade nuclear material is any fissionable nuclear material that is pure enough to make a nuclear weapon and has properties that make it particularly suitable for nuclear weapons use. Plutonium and uranium in grades normally used in nuclear weapons are the most common examples.

Uranium-236 (236U) is an isotope of uranium that is neither fissile with thermal neutrons, nor very good fertile material, but is generally considered a nuisance and long-lived radioactive waste. It is found in spent nuclear fuel and in the reprocessed uranium made from spent nuclear fuel.

Reactor-grade plutonium (RGPu) is the isotopic grade of plutonium that is found in spent nuclear fuel after the uranium-235 primary fuel that a nuclear power reactor uses has burnt up. The uranium-238 from which most of the plutonium isotopes derive by neutron capture is found along with the U-235 in the low enriched uranium fuel of civilian reactors.