History

Settling the Midwest

Settlers without legal claims, derisively called "squatters", had been moving into the Midwest for years before 1776. They pushed further and further down the Ohio River during the 1760s and 1770s and sometimes engaged in conflict and competition with the Native Americans. British officials were outraged--they wanted the West to be reserved for Indians but could do little to stop the Americans. [2] The British had a long-standing goal of establishing a Native American buffer state in the American Midwest to resist American westward expansion. [3]

With victory in the American Revolution, the new government considered evicting the squatters from areas that were now federally owned public lands. [4] In 1785, soldiers under General Josiah Harmar were sent into the Ohio country to destroy the crops and burn down the homes of any squatters they found living there. Overall, federal policy was to move Indians to western lands, such as the Indian Territory in modern Oklahoma, and have a very large numbers of farmers replace a small number of hunters. [5] [6] [7] [8]

Congress repeatedly debated how to legalize settlements. Whigs like Henry Clay wanted the government to get maximum revenue, and wanted stable middle-class law-abiding settlements of the sort that supported towns and bankers. Jacksonian Democrats like Thomas Hart Benton wanted the support of poor farmers, who reproduced rapidly, had little cash, and were eager to acquire cheap land in the West. Democrats did not want a big government and keeping revenues low helped that cause. Democrats avoided words like "squatter" and regarded "actual settlers" as those who gained title to land, settled on it, and then improved upon it by building a house, clearing the ground, and planting crops. [9] [10] [11] [12]

A number of means facilitated the legal settlement of the territories in the Midwest: land speculation, federal public land auctions, bounty land grants in lieu of pay to military veterans, and, later, preemption rights for squatters. Ultimately, as they shed the image of being outside the law and fashioned themselves into pioneers, squatters were increasingly able to purchase the lands on which they had settled for the minimum price, thanks to various preemption acts and laws passed throughout the 1810s-1840s. In Washington, Jacksonian Democrats favored squatter rights and banker-oriented Whigs were opposed. The Democrats prevailed. [13] [14] [15] [16]

Homestead laws after 1862

The Homestead Acts legally recognized the concept of the homestead principle and distinguished it from squatting, since the law gave homesteaders a legal way to occupy "unclaimed" lands. President Abraham Lincoln signed the Homestead Act of 1862, which was enacted to foster the reallocation of "unsettled" land in the West. The law applied to US citizens as well as immigrants. It required a five-year commitment, during which time the land owner had to build a twelve-by-fourteen foot dwelling, and develop or work the 160-acre (0.65 km2) plot of land allocated. After five years of positively contributing to the homestead, the applicant could file a request for the deed to the property, which entailed sending paperwork to the General Land Office in Washington, D.C., and, from there, "valid claims were granted patent free and clear". [17]

California

During and after the California Gold Rush (1848–1855) new arrivals squatted land. Under the California Land Act of 1851, squatters made 813 claims as the population in California increased from 15,000 in 1848 to 265,000 in 1852. [18] The Squatters' riot of 1850 was a conflict between squatters and the government of Sacramento, California. [19] Squatting occurred during World War II when Japanese-Americans were sent to Manzanar concentration camp. Buildings which had been left abandoned around the Little Tokyo area in Los Angeles were occupied by African American migrant workers moving to California to work in the armaments factories. [20] In the 1970s and 1980s, gold mining again became an issue in places such as Idaho. [21] In 1975, over 2,000 illegal operations were reported in California and the Forest Service took action on what it called "occupancy trespass". [22]

Great Depression of 1930s

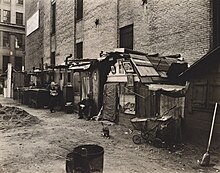

Hoovervilles were shanty towns built by homeless people across the US during the Great Depression in the 1930s. They were named after Republican Herbert Hoover. [23]

Great Recession (2007–2009)

During the Great Recession (2007–2009) shanty towns again appeared across the US, for example Dignity Village in Portland, Oregon, Umoja Village in Miami and Nickelsville in Seattle. [24] [25] [26] After the United States housing bubble collapsed and banks have foreclosed on many homeowners unable to pay their mortgages. [27] Sovereign citizens in Georgia have squatted million dollar homes in Dekalb and Rockdale counties using fake deeds. [28]

According to a Florida based lawyer, "we haven't seen this kind of level of squatters since the Great Depression". [29] In the San Francisco Bay Area, local NBC News reported that people were even squatting on their own foreclosed properties. [30] Michael Feroli, chief economist at JPMorgan Chase, has commented on the boon to the economy of "squatter rent" or the extra income made available for spending by people not fulfilling their mortgage repayments. [31]