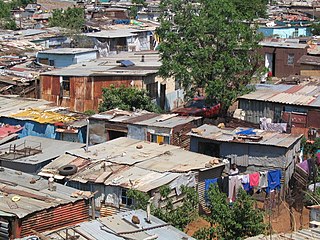

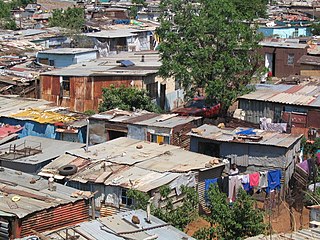

Squatting is the action of occupying an abandoned or unoccupied area of land or a building, usually residential, that the squatter does not own, rent or otherwise have lawful permission to use. The United Nations estimated in 2003 that there were one billion slum residents and squatters globally. Squatting occurs worldwide and tends to occur when people who are poor and homeless find empty buildings or land to occupy for housing. It has a long history, broken down by country below.

A shanty town or squatter area is a settlement of improvised buildings known as shanties or shacks, typically made of materials such as mud and wood. A typical shanty town is squatted and in the beginning lacks adequate infrastructure, including proper sanitation, safe water supply, electricity and street drainage. Over time, shanty towns can develop their infrastructure and even change into middle class neighbourhoods. They can be small informal settlements or they can house millions of people.

Vreed en Hoop is a village at the mouth of the Demerara River on its left bank, in the Essequibo Islands-West Demerara region of Guyana, located at sea level. It is the location of the Regional Democratic Council office making it the administrative center for the region. There is also a police station, magistrate's court and post office.

Sophia is a ward of Georgetown, the capital of Guyana. It's a predominantly Afro-Guyanese community, and one of Georgetown's poorest neighborhoods.

Informal housing or informal settlement can include any form of housing, shelter, or settlement which is illegal, falls outside of government control or regulation, or is not afforded protection by the state. As such, the informal housing industry is part of the informal sector.

Squatting in Zimbabwe is the settlement of land or buildings without the permission of the owner. Squatting began under colonialism. After Zimbabwe was created in 1980, peasant farmers and squatters disputed the distribution of land. Informal settlements have developed on the periphery of cities such as Chitungwiza and the capital Harare. In 2005, Operation Murambatsvina evicted an estimated 700,000 people.

Squatting in Fiji is defined as being "a resident of a dwelling which is illegal according to planning by-laws regardless of whether the landowner has given consent". As of 2018, an estimated 20% of the total population was squatting, including people living on land owned by indigenous clans with informal permission. Most squatters are on the larger islands such as Vanua Levu and Viti Levu.

Squatting in Namibia is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. After Namibian independence in 1990, squatting increased as people migrated to the cities. By 2020, 401,748 people were living in 113 informal settlements across the country.

Squatting in Ghana is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. Informal settlements are found in cities such as Kumasi and the capital Accra. Ashaiman, now a town of 100,000 people, was swelled by squatters. In central Accra, next to Agbogbloshie, the Old Fadama settlement houses an estimated 80,000 people and is subject to a controversial discussion about eviction. The residents have been supported by Amnesty International, the Centre on Housing Rights and Evictions and Shack Dwellers International.

Squatting in the Republic of Vanuatu is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. After independence in 1980, informal settlements developed in cities such as Luganville and the capital Port Vila. Land in Vanuatu is either custom land owned by indigenous peoples or public land owned by the republic.

Squatting in Chile is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. From the 1960s onwards, informal settlements known as callampas were permitted although there were also evictions such as the massacre of Puerto Montt in 1969. In the 1970s, the government of Salvador Allende encouraged occupations, then following the coup d'état, the military junta repressed squatting. Callampas then became known as campamentos.

Squatting in Pakistan is the occupation of unused land or derelict buildings without the permission of the owner. Squatted informal settlements formed following the creation of Pakistan in 1947. They were known first as "bastis" then later "katchi abadis" and the inhabitants were forcibly resettled under military rule. By 2007, there were 7.5 million squatters in Karachi alone. The Sindh Katchi Abadi Authority (SKAA) announced in 2019 that a total of 1,414 katchi abadis had been located and 1,006 of those had been contacted with regards to beginning a regularization process.

Squatting in Sudan is defined as the "Acquisition and construction of land, within the city boundaries for the purpose of housing in contradiction to Urban Planning and Land laws and building regulations." These informal settlements arose in Khartoum from the 1920s onwards, swelling in the 1960s. By the 1980s, the government was clearing settlements in Khartoum and regularizing them elsewhere. It was estimated that in 2015 that were 200,000 squatters in Khartoum, 180,000 in Nyala, 60,000 in Kassala, 70,000 in Port Sudan and 170,000 in Wad Madani.

Squatting in Venezuela is the occupation of derelict buildings or unused land without the permission of the owner. Informal settlements, known first as "ranchos" and then "barrios", are common. In the capital Caracas notable squats have included the 23 de Enero housing estate, Centro Financiero Confinanzas and El Helicoide, a former shopping centre which is now a notorious prison.

Squatting in the Philippines occurs when people build makeshift houses called "barong-barong"; urban areas such as Metro Manila and Metro Davao have large informal settlements. The Philippine Statistics Authority has defined a squatter, or alternatively "informal dwellers", as "One who settles on the land of another without title or right or without the owner's consent whether in urban or rural areas". Squatting is criminalized by the Urban Development and Housing Act of 1992, also known as the Lina Law. There have been various attempts to regularize squatter settlements, such as the Zonal Improvement Program and the Community Mortgage Program. In 2018, the Philippine Statistics Authority estimated that out of the country's population of about 106 million, 4.5 million were homeless.

Squatting in Bangladesh occurs when squatters make informal settlements known as "bastees" on the periphery of cities such as Chittagong, Dhaka and Khulna. As of 2013, almost 35 per cent of Bangladesh's urban population lived in informal settlements.

Squatting in Nepal occurs when people live on land or in buildings without the valid land ownership certificate. The number of squatters has increased rapidly since the 1980s, as a result of factors such as internal migration to Kathmandu and civil war. In March 2021, the chairperson of the Commission on Landless Squatters stated that all landless squatters would receive ownership certificates within the following eighteen months.

Squatting in Angola occurs when displaced peoples occupy informal settlements in coastal cities such as the capital Luanda. The Government of Angola has been criticized by human rights groups for forcibly evicting squatters and not resettling them.

Squatting in Mexico has occurred on the periphery of Mexico City from the 19th century onwards. As of 2017, an estimated 25 per cent of Mexico's urban population lived in informal settlements. In Mexico City, there are self-managed social centres. The CORETT program aims to help squatters to register their land plots

In Algeria, the high cost of housing leads to informal settlements, many of which are on squatted land. Another factor causing squatting has been displacement, since during the Algerian War of 1954 until 1962 up to 2.5 million people were forcibly resettled. In the north-eastern city of Annaba, squats sprang up after the country became independent in 1962 and tend to lack connection to sanitation and electricity. The Directorate for Planning and Construction (DUC) announced in 2007 that there were 3,612 buildings in more than 104 informal settlements across the province of Tizi Ouzou.