Omniscience is the capacity to know everything. In Hinduism, Sikhism and the Abrahamic religions, this is an attribute of God. In Jainism, omniscience is an attribute that any individual can eventually attain. In Buddhism, there are differing beliefs about omniscience among different schools.

Philosophy of religion is "the philosophical examination of the central themes and concepts involved in religious traditions". Philosophical discussions on such topics date from ancient times, and appear in the earliest known texts concerning philosophy. The field is related to many other branches of philosophy, including metaphysics, epistemology, logic and ethics.

Predestination, in theology, is the doctrine that all events have been willed by God, usually with reference to the eventual fate of the individual soul. Explanations of predestination often seek to address the paradox of free will, whereby God's omniscience seems incompatible with human free will. In this usage, predestination can be regarded as a form of religious determinism; and usually predeterminism, also known as theological determinism.

Free will is the capacity or ability to choose between different possible courses of action.

Determinism is the philosophical view that all events in the universe, including human decisions and actions, are causally inevitable. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and considerations. Like eternalism, determinism focuses on particular events rather than the future as a concept. The opposite of determinism is indeterminism, or the view that events are not deterministically caused but rather occur due to chance. Determinism is often contrasted with free will, although some philosophers claim that the two are compatible.

In classical theistic and monotheistic theology, the doctrine of Divine Simplicity says that God is simple.

Open theism, also known as openness theology, is a theological movement that has developed within Christianity as a rejection of the synthesis of Greek philosophy and Christian theology. It is a version of free will theism and arises out of the free will theistic tradition of the church, which goes back to the early church fathers. Open theism is typically advanced as a biblically motivated and logically consistent theology of human and divine freedom, with an emphasis on what this means for the content of God's foreknowledge and exercise of God's power.

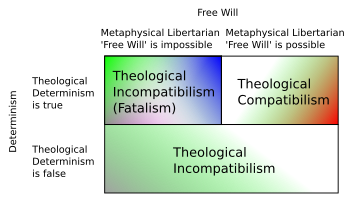

The argument from free will, also called the paradox of free will or theological fatalism, contends that omniscience and free will are incompatible and that any conception of God that incorporates both properties is therefore inconceivable. See the various controversies over claims of God's omniscience, in particular the critical notion of foreknowledge. These arguments are deeply concerned with the implications of predestination.

The philosophical term incompatibilism was coined in the 1960s, most likely by philosopher Keith Lehrer, to name the view that the thesis of determinism is logically incompatible with the classical thesis of free will. The term compatibilism was coined to name the view that the classical free will thesis is logically compatible with determinism, i.e. it is possible for an ordinary human to exercise free will even in a universe at which determinism is true. These terms were originally coined for use within a research paradigm that was dominant among academics during the so-called "classical period" from the 1960s to 1980s, or what has been called the "classical analytic paradigm". Within the classical analytic paradigm, the problem of free will and determinism was understood as a Compatibility Question: "Is it possible for an ordinary human to exercise free will when determinism is true?" Those working in the classical analytic paradigm who answered "no" were incompatibilists in the original, classical-analytic sense of the term, now commonly called classical incompatibilists; they proposed that determinism precludes free will because it precludes our ability to do otherwise. Those who answered "yes" were compatibilists in the original sense of the term, now commonly called classical compatibilists. Given that classical free will theorists agreed that it is at least metaphysically possible for an ordinary human to exercise free will, all classical compatibilists accepted a compossibilist account of free will and all classical incompatibilists accepted a libertarian account of free will.

Fatalism is a family of related philosophical doctrines that stress the subjugation of all events or actions to fate or destiny, and is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are thought to be inevitable; with an individual believing they cannot control what happens to them.

Compatibilism is the belief that free will and determinism are mutually compatible and that it is possible to believe in both without being logically inconsistent. The opposing belief, that the thesis of determinism is logically incompatible with the classical thesis of free will, is known as "incompatibilism".

Molinism, named after 16th-century Spanish Jesuit priest and Roman Catholic theologian Luis de Molina, is the thesis that God has middle knowledge : the knowledge of counterfactuals, particularly counterfactuals regarding human action. It seeks to reconcile the apparent tension of divine providence and human free will. Prominent contemporary Molinists include William Lane Craig, Alfred Freddoso, Alvin Plantinga, Thomas Flint, Kenneth Keathley, Dave Armstrong, John D. Laing, Kirk R. MacGregor, and J.P. Moreland.

Predeterminism is the philosophy that all events of history, past, present and future, have been already decided or are already known, including human actions.

Peter van Inwagen is an American analytic philosopher and the John Cardinal O'Hara Professor of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame. He is also a research professor of philosophy at Duke University each spring. He previously taught at Syracuse University, earning his PhD from the University of Rochester in 1969 under the direction of Richard Taylor. Van Inwagen is one of the leading figures in contemporary metaphysics, philosophy of religion, and philosophy of action. He was the president of the Society of Christian Philosophers from 2010 to 2013.

Free will in theology is an important part of the debate on free will in general. Religions vary greatly in their response to the standard argument against free will and thus might appeal to any number of responses to the paradox of free will, the claim that omniscience and free will are incompatible.

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that investigates principles of reality transcending those of any particular science. Cosmology and ontology are traditional branches of metaphysics. It is concerned with explaining the fundamental nature of being and the world. Someone who studies metaphysics can be called either a "metaphysician" or a "metaphysicist".

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to atheism:

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to metaphysics:

Alvin Plantinga's free-will defense is a logical argument developed by the American analytic philosopher Alvin Plantinga and published in its final version in his 1977 book God, Freedom, and Evil. Plantinga's argument is a defense against the logical problem of evil as formulated by the philosopher J. L. Mackie beginning in 1955. Mackie's formulation of the logical problem of evil argued that three attributes of God, omniscience, omnipotence, and omnibenevolence, in orthodox Christian theism are logically incompatible with the existence of evil.

Free will in antiquity is a philosophical and theological concept. Free will in antiquity was not discussed in the same terms as used in the modern free will debates, but historians of the problem have speculated who exactly was first to take positions as determinist, libertarian, and compatibilist in antiquity. There is wide agreement that these views were essentially fully formed over 2000 years ago. Candidates for the first thinkers to form these views, as well as the idea of a non-physical "agent-causal" libertarianism, include Democritus, Aristotle, Epicurus, Chrysippus, and Carneades.