Ukraine used to attract more than 20 million foreign citizens every year. But since 2014 this has lowered to about 10 million. Visitors primarily come from Eastern Europe, but also from Western Europe, as well as Turkey and Israel.

Chernihiv is a city and municipality in northern Ukraine, which serves as the administrative center of Chernihiv Oblast and Chernihiv Raion within the oblast. Chernihiv's population is 282,747.

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv, Ukraine, is an architectural monument of Kievan Rus'. The former cathedral is one of the city's best known landmarks and the first heritage site in Ukraine to be inscribed on the World Heritage List along with the Kyiv Cave Monastery complex. Aside from its main building, the cathedral includes an ensemble of supporting structures such as a bell tower and the House of Metropolitan. In 2011 the historic site was reassigned from the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Regional Development of Ukraine to the Ministry of Culture of Ukraine. One of the reasons for the move was that both Saint Sophia Cathedral and Kyiv Pechersk Lavra are recognized by the UNESCO World Heritage Program as one complex, while in Ukraine the two were governed by different government entities. It is currently a museum.

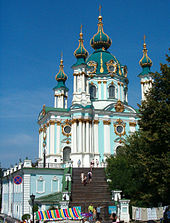

St Andrew's Church is an Orthodox church in Kyiv, constructed between 1747 and 1754 to a design by the Italian architect Bartolomeo Rastrelli. It is a rare example of Elizabethan Baroque in Ukraine. Situated on a steep hill, where Andrew the Apostle is believed to have foretold the great future of the place as the cradle of Christianity in the Slavic lands, the church overlooks the historic Podil neighborhood. Since 1968, the building has been a museum, part of the National Sanctuary "Sophia of Kyiv" as a landmark of cultural heritage.

St Volodymyr's Cathedral is a cathedral in the centre of Kyiv. It is one of the city's major landmarks and was the mother cathedral of the Ukrainian Orthodox Church – Kyiv Patriarchate before the Unification council of the Eastern Orthodox churches of Ukraine.

Ukrainian Baroque, also known as Cossack Baroque or Mazepa Baroque, is an architectural style that was widespread in the Ukrainian lands in the 17th and 18th centuries. It was the result of a combination of local architectural traditions and European Baroque.

The architecture of Russia refers to the architecture of modern Russia as well as the architecture of both the original Kievan Rus', the Russian principalities, and Imperial Russia. Due to the geographical size of modern and Imperial Russia, it typically refers to architecture built in European Russia, as well as European influenced architecture in the conquered territories of the Empire.

The Golden Gate of Kyiv was the main gate in the 11th century fortifications of Kyiv, the capital of Kievan Rus'. It was named in imitation of the Golden Gate of Constantinople. The structure was dismantled in the Middle Ages, leaving few vestiges of its existence. It was rebuilt completely by the Soviet authorities in 1982, though no images of the original gates have survived. The decision has been immensely controversial because there were many competing reconstructions of what the original gate might have looked like.

The architecture of Kievan Rus' comes from the medieval state of Kievan Rus' which incorporated parts of what is now modern Ukraine, Russia, and Belarus, and was centered on Kiev and Novgorod. Its architecture is the earliest period of Russian and Ukrainian architecture, using the foundations of Byzantine culture but with great use of innovations and architectural features. Most remains are Russian Orthodox churches or parts of the gates and fortifications of cities.

St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery is a monastery in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, dedicated to Saint Michael the Archangel. It is located on the edge of the bank of the Dnipro river, to the northeast of the St Sophia Cathedral. The site is located in the historical administrative neighbourhood of Uppertown and overlooks Podil, the city's historical commercial and merchant quarter. The monastery has been the headquarters of the Orthodox Church of Ukraine since December 2018.

Zoloti Vorota is a station on the Kyiv Metro system that serves Kyiv, the capital city of Ukraine. The station was opened as part of the first segment of the Syretsko-Pecherska Line on 31 December 1989. It serves as a transfer station to the Teatralna station of the Sviatoshynsko-Brovarska Line. It is located near the city's Golden Gate, from which the station takes its name.

St. Cyril's Monastery is a medieval monastery in Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine. The monastery contains the famous St. Cyril's Church, an important specimen of Kievan Rus' architecture of the 12th century, and combining elements of the 17th and 19th centuries. However, being largely Ukrainian Baroque on the outside, the church retains its original Kievan Rus' interior.

St. George's Cathedral is a baroque-rococo cathedral located in the city of Lviv, the historic capital of western Ukraine. It was constructed between 1744-1760 on a hill overlooking the city. This is the third manifestation of a church to inhabit the site since the 13th century, and its prominence has repeatedly made it a target for invaders and vandals. The cathedral also holds a predominant position in Ukrainian religious and cultural terms. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the cathedral served as the mother church of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church.

The Major Archeparchy of Kyiv–Galicia (Kyiv–Halych) is a Ukrainian Greek Catholic Major Archeparchy of the Catholic Church, that is located in Ukraine. It was erected on 21 August 2005 with the approval of Pope Benedict XVI. There are other territories of the Church that are not located in Ukraine. The cathedral church — the Cathedral of the Resurrection of Christ — is situated in the city of Kyiv. The metropolitan bishop is — ex officio — the Primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church. The incumbent major archbishop is Sviatoslav Shevchuk.

The architecture of Poland includes modern and historical monuments of architectural and historical importance.

The Pyrohoshcha Dormition of the Mother of God Church or simply Pyrohoshcha Church is an Orthodox church in Kyiv in the historical neighbourhood Podil. The original church was built in 1130s by the Mstyslav I the Great of Kyiv. It was the main church of Podil, and was a temporary cathedral of Kyiv Metropolitanate in the early 17 century. In 1613 the church was reconstructured in Renaissance style, and then in 18th-19th centuries was rebuilt in Ukrainian Baroque and Neoclassicism styles.

Volodymyrska Street is a street in the center of Kyiv, the capital of Ukraine, which is named after the prince of Kievan Rus' Vladimir the Great and which is one of the oldest streets in the city, and arguably among the oldest constantly inhabited residential street in Europe. There are many educational, culture and government institutions on this street, as well as historical monuments. Four buildings from Volodymyrska Street are depicted on reverses of Ukrainian hryvnia banknotes.

The architecture of Belarus spans a variety of historical periods and styles and reflects the complex history, geography, religion and identity of the country. Several buildings in Belarus have been designated as UNESCO World Heritage Sites in recognition of their cultural heritage, and others have been placed on the tentative list.

The Bell Tower of Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv is a monument of Ukrainian architecture in the style of Ukrainian (Cossack) Baroque. It is one of the Ukrainian national symbols and symbols of the city of Kyiv.

The demolition of St. Michael's Golden-Domed Monastery by dynamite took place on 14 August 1937. The bell tower, the Economic Gate and the monastery's walls were also destroyed.