Futurism was an artistic and social movement that originated in Italy, and to a lesser extent in other countries, in the early 20th century. It emphasized dynamism, speed, technology, youth, violence, and objects such as the car, the airplane, and the industrial city. Its key figures included the Italians Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, Umberto Boccioni, Carlo Carrà, Fortunato Depero, Gino Severini, Giacomo Balla, and Luigi Russolo. Italian Futurism glorified modernity and according to its doctrine, aimed to liberate Italy from the weight of its past. Important Futurist works included Marinetti's 1909 Manifesto of Futurism, Boccioni's 1913 sculpture Unique Forms of Continuity in Space, Balla's 1913–1914 painting Abstract Speed + Sound, and Russolo's The Art of Noises (1913).

Retrofuturism is a movement in the creative arts showing the influence of depictions of the future produced in an earlier era. If futurism is sometimes called a "science" bent on anticipating what will come, retrofuturism is the remembering of that anticipation. Characterized by a blend of old-fashioned "retro styles" with futuristic technology, retrofuturism explores the themes of tension between past and future, and between the alienating and empowering effects of technology. Primarily reflected in artistic creations and modified technologies that realize the imagined artifacts of its parallel reality, retrofuturism can be seen as "an animating perspective on the world".

Suprematism is an early twentieth-century art movement focused on the fundamentals of geometry, painted in a limited range of colors. The term suprematism refers to an abstract art based upon "the supremacy of pure artistic feeling" rather than on visual depiction of objects.

Dame Zaha Mohammad Hadid was an Iraqi-British architect, artist and designer, recognized as a major figure in architecture of the late-20th and early-21st centuries. Born in Baghdad, Iraq, Hadid studied mathematics as an undergraduate and then enrolled at the Architectural Association School of Architecture in 1972. In search of an alternative system to traditional architectural drawing, and influenced by Suprematism and the Russian avant-garde, Hadid adopted painting as a design tool and abstraction as an investigative principle to "reinvestigate the aborted and untested experiments of Modernism [...] to unveil new fields of building".

Archigram was an avant-garde British architectural group whose unbuilt projects and media-savvy provocations "spawned the most influential architectural movement of the 1960's," according to Peter Cook, in the Princeton Architectural Press study Archigram (1999). Neofuturistic, anti-heroic, and pro-consumerist, the group drew inspiration from technology in order to create a new reality that was expressed through hypothetical projects, i.e., its buildings were never built, although the group did produce what the architectural historian Charles Jencks called "a series of monumental objects (one hesitates in calling them buildings since most of them moved, grew, flew, walked, burrowed or just sank under the water." The works of Archigram had a neofuturistic slant, influenced by Antonio Sant'Elia's works. Buckminster Fuller and Yona Friedman were also important sources of inspiration.

Italian futurist cinema was the oldest movement of European avant-garde cinema. Italian futurism, an artistic and social movement, impacted the Italian film industry from 1916 to 1919. It influenced Russian Futurist cinema and German Expressionist cinema. Its cultural importance was considerable and influenced all subsequent avant-gardes, as well as some authors of narrative cinema; its echo expands to the dreamlike visions of some films by Alfred Hitchcock.

Cubo-Futurism or Kubo-Futurizm was an art movement, developed within Russian Futurism, that arose in early 20th century Russian Empire, defined by its amalgamation of the artistic elements found in Italian Futurism and French Analytical Cubism. Cubo-Futurism was the main school of painting and sculpture practiced by the Russian Futurists. In 1913, the term "Cubo-Futurism" first came to describe works from members of the poetry group "Hylaeans", as they moved away from poetic Symbolism towards Futurism and zaum, the experimental "visual and sound poetry of Kruchenykh and Khlebninkov". Later in the same year the concept and style of "Cubo-Futurism" became synonymous with the works of artists within Ukrainian and Russian post-revolutionary avant-garde circles as they interrogated non-representational art through the fragmentation and displacement of traditional forms, lines, viewpoints, colours, and textures within their pieces. The impact of Cubo-Futurism was then felt within performance art societies, with Cubo-Futurist painters and poets collaborating on theatre, cinema, and ballet pieces that aimed to break theatre conventions through the use of nonsensical zaum poetry, emphasis on improvisation, and the encouragement of audience participation.

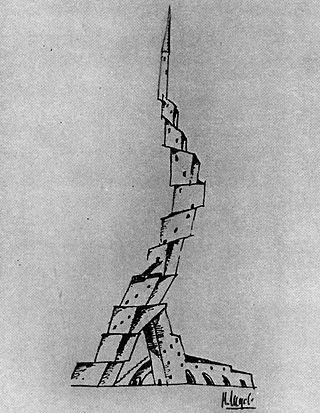

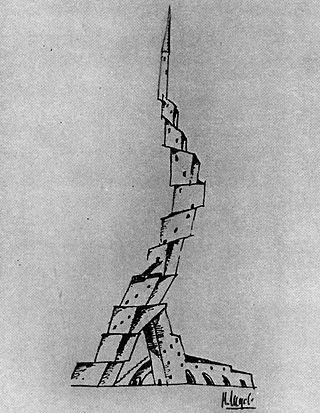

Futurist architecture is an early-20th century form of architecture born in Italy, characterized by long dynamic lines, suggesting speed, motion, urgency and lyricism: it was a part of Futurism, an artistic movement founded by the poet Filippo Tommaso Marinetti, who produced its first manifesto, the Manifesto of Futurism, in 1909. The movement attracted not only poets, musicians, and artists but also a number of architects. A cult of the Machine Age and even a glorification of war and violence were among the themes of the Futurists - several prominent futurists were killed after volunteering to fight in World War I. The latter group included the architect Antonio Sant'Elia, who, though building little, translated the futurist vision into an urban form.

Visionary architecture is a design that only exists on paper or displays idealistic or impractical qualities. The term originated from an exhibit at the Museum of Modern Art in 1960. Visionary architects are also known as paper architects because their improbable works exist only as drawings, collages, or models. Their designs show unique, creative concepts that are unrealistic or impossible except in the design environment.

Contemporary architecture is the architecture of the 21st century. No single style is dominant. Contemporary architects work in several different styles, from postmodernism, high-tech architecture and new references and interpretations of traditional architecture to highly conceptual forms and designs, resembling sculpture on an enormous scale. Some of these styles and approaches make use of very advanced technology and modern building materials, such as tube structures which allow construction of buildings that are taller, lighter and stronger than those in the 20th century, while others prioritize the use of natural and ecological materials like stone, wood and lime. One technology that is common to all forms of contemporary architecture is the use of new techniques of computer-aided design, which allow buildings to be designed and modeled on computers in three dimensions, and constructed with more precision and speed.

Megastructure is an architectural and urban concept of the post-war era, which envisions a city or an urban form that could be encased in a massive single human-made structure or a relatively small number of interconnected structures. In a megastructural project, orders and hierarchies are created with large and permanent structures supporting small and transitional ones.

Russian Futurism is the broad term for a movement of Russian poets and artists who adopted the principles of Filippo Marinetti's "Manifesto of Futurism", which espoused the rejection of the past, and a celebration of speed, machinery, violence, youth, industry, destruction of academies, museums, and urbanism; it also advocated for modernization and cultural rejuvenation.

Constructivist architecture was a constructivist style of modern architecture that flourished in the Soviet Union in the 1920s and early 1930s. Abstract and austere, the movement aimed to reflect modern industrial society and urban space, while rejecting decorative stylization in favor of the industrial assemblage of materials. Designs combined advanced technology and engineering with an avowedly communist social purpose. Although it was divided into several competing factions, the movement produced many pioneering projects and finished buildings, before falling out of favor around 1932. It has left marked effects on later developments in architecture.

Giovanni Lista is an Italian art historian and art critic born in Italy on February 13, 1943, at Castiglione del Lago (Perugia) and resides in Paris. He is a specialist in the artistic cultural scene of the 1920s, particularly in Futurism.

The Design Futures Council is an interdisciplinary network of design, product, and construction leaders exploring global trends, challenges, and opportunities to advance innovation and shape the future of the industry and environment. Members include architecture and design firms, building product manufacturers, service providers, and forward-thinking AEC firms of all sizes that take an active interest in their future.

Unicorn Island is a planned development of office buildings and landscaping designed to attract and foster technology companies with valuations of more than $1 billion, "unicorns." Its area spans 67 hectares. Zaha Hadid Architects is developing the plan for the Chengdu government on the eastern shore of Xin Long Lake in Chengdu, China. Construction of the first building, a conference center, neared completion during 2020.

Parametricism is a style within contemporary avant-garde architecture, promoted as a successor to Modern and Postmodern architecture. The term was coined in 2008 by Patrik Schumacher, an architectural partner of Zaha Hadid (1950–2016). Parametricism has its origin in parametric design, which is based on the constraints in a parametric equation. Parametricism relies on programs, algorithms, and computers to manipulate equations for design purposes.

Avant-garde architecture is architecture which is innovative and radical. There have been a variety of architects and movements whose work has been characterised in this way, especially Modernism. Other examples include Constructivism, Neoplasticism, Neo-futurism, Deconstructivism, Parametricism and Expressionism.

SOHO China is a Chinese building developer, primarily in the office and commercial sector, with some residential and mixed-use properties in its portfolio. The company, which uses the name "SOHO" in both English and Chinese contexts, was founded in 1995 by Chairman Pan Shiyi (潘石屹) and CEO Zhang Xin (张欣). The name SOHO comes from the phrase "Smart Office, Home Office" as the company decided to combine office rooms and residential apartments in the same building to facilitate a comfortable and productive environment.

The Changsha Meixihu International Culture and Arts Centre is a cultural complex located in the Meixihu subdistrict of Changsha, Hunan, China. It was completed in 2019. The complex was designed by British architectural firm Zaha Hadid Architects.