Related Research Articles

In psychoanalytic theory, the id, ego and superego are three distinct, interacting agents in the psychic apparatus, defined in Sigmund Freud's structural model of the psyche. The three agents are theoretical constructs that Freud employed to describe the basic structure of mental life as it was encountered in psychoanalytic practice. Freud himself used the German terms das Es, Ich, and Über-Ich, which literally translate as "the it", "I", and "over-I". The Latin terms id, ego and superego were chosen by his original translators and have remained in use.

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of personality organization and the dynamics of personality development relating to the practice of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology. First laid out by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, psychoanalytic theory has undergone many refinements since his work. The psychoanalytic theory came to full prominence in the last third of the twentieth century as part of the flow of critical discourse regarding psychological treatments after the 1960s, long after Freud's death in 1939. Freud had ceased his analysis of the brain and his physiological studies and shifted his focus to the study of the psyche, and on treatment using free association and the phenomena of transference. His study emphasized the recognition of childhood events that could influence the mental functioning of adults. His examination of the genetic and then the developmental aspects gave the psychoanalytic theory its characteristics. Starting with his publication of The Interpretation of Dreams in 1899, his theories began to gain prominence.

Projection is a psychological phenomenon where feelings directed towards the self are displaced towards other people.

The genital stage in psychoanalysis is the term used by Sigmund Freud to describe the final stage of human psychosexual development. The individual develops a strong sexual interest in people outside of the family.

In psychoanalysis, anticathexis, or countercathexis, is the energy used by the ego to bind the primitive impulses of the Id. Sometimes the ego follows the instructions of the superego in doing so; sometimes however it develops a double-countercathexis, so as to block feelings of guilt and anxiety deriving from the superego, as well as id impulses.

In psychology, intellectualization (intellectualisation) is a defense mechanism by which reasoning is used to block confrontation with an unconscious conflict and its associated emotional stress – where thinking is used to avoid feeling. It involves emotionally removing one's self from a stressful event. Intellectualization may accompany, but is different from, rationalization, the pseudo-rational justification of irrational acts.

In classical Freudian psychoanalytic theory, the death drive is the drive toward death and destruction, often expressed through behaviors such as aggression, repetition compulsion, and self-destructiveness. It was originally proposed by Sabina Spielrein in her paper "Destruction as the Cause of Coming Into Being" in 1912, which was then taken up by Sigmund Freud in 1920 in Beyond the Pleasure Principle. This concept has been translated as "opposition between the ego or death instincts and the sexual or life instincts". In Beyond thePleasure Principle, Freud used the plural "death drives" (Todestriebe) much more frequently than the singular.

Repetition compulsion is the unconscious tendency of a person to repeat a traumatic event or its circumstances. This may take the form of symbolically or literally re-enacting the event, or putting oneself in situations where the event is likely to occur again. Repetition compulsion can also take the form of dreams in which memories and feelings of what happened are repeated, and in cases of psychosis, may even be hallucinated.

In Freudian psychoanalysis, the ego ideal is the inner image of oneself as one wants to become. It consists of "the individual's conscious and unconscious images of what he would like to be, patterned after certain people whom ... he regards as ideal."

Otto Fenichel was a psychoanalyst of the so-called "second generation".

Splitting is the failure in a person's thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both perceived positive and negative qualities of something into a cohesive, realistic whole. It is a common defense mechanism wherein the individual tends to think in extremes. This kind of dichotomous interpretation is contrasted by an acknowledgement of certain nuances known as "shades of gray".

Identification is a psychological process whereby the individual assimilates an aspect, property, or attribute of the other and is transformed wholly or partially by the model that other provides. It is by means of a series of identifications that the personality is constituted and specified. The roots of the concept can be found in Freud's writings. The three most prominent concepts of identification as described by Freud are: primary identification, narcissistic (secondary) identification and partial (secondary) identification.

Fixation is a concept that was originated by Sigmund Freud (1905) to denote the persistence of anachronistic sexual traits. The term subsequently came to denote object relationships with attachments to people or things in general persisting from childhood into adult life.

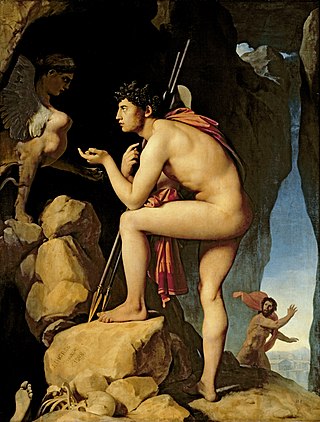

In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex refers to a son's sexual attitude towards his mother and concomitant hostility toward his father, first formed during the phallic stage of psychosexual development. A daughter's attitude of desire for her father and hostility toward her mother is referred to as the feminine Oedipus complex. The general concept was considered by Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), although the term itself was introduced in his paper A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men (1910).

Penis envy is a stage in Sigmund Freud's theory of female psychosexual development, in which young girls experience anxiety upon realization that they do not have a penis. Freud considered this realization a defining moment in a series of transitions toward a mature female sexuality. In Freudian theory, the penis envy stage begins the transition from attachment to the mother to competition with the mother for the attention and affection of the father. The young boy's realization that women do not have a penis is thought to result in castration anxiety.

Postponement of affect is a defence mechanism which may be used against a variety of feelings or emotions. Such a "temporal displacement, resulting simply in a later appearance of the affect reaction and in thus preventing the recognition of the motivating connection, is most frequently used against the affects of rage and grief".

In psychology, narcissistic withdrawal is a stage in narcissism and a narcissistic defense characterized by "turning away from parental figures, and by the fantasy that essential needs can be satisfied by the individual alone". In adulthood, it is more likely to be an ego defense with repressed origins. Individuals feel obliged to withdraw from any relationship that threatens to be more than short-term, avoiding the risk of narcissistic injury, and will instead retreat into a comfort zone. The idea was first described by Melanie Klein in her psychoanalytic research on stages of narcissism in children.

Narcissistic defenses are those processes whereby the idealized aspects of the self are preserved, and its limitations denied. They tend to be rigid and totalistic. They are often driven by feelings of shame and guilt, conscious or unconscious.

Narcissistic neurosis is a term introduced by Sigmund Freud to distinguish the class of neuroses characterised by their lack of object relations and their fixation upon the early stage of libidinal narcissism. The term is less current in contemporary psychoanalysis, but still a focus for analytic controversy.

Some Character-Types Met within Psycho-Analytic Work is an essay by Sigmund Freud from 1916, comprising three character studies—of what he called 'The Exceptions', 'Those Wrecked by Success' and 'Criminals from a Sense of Guilt'.

References

- ↑ Laplanche, J. and Pontalis, J-B. (1973), The language of psycho-analysis (D. Nicholson-Smith, Trans). New York: Norton.

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, Case Studies II (London 1991) p. 70

- ↑ Freud, Studies p. 72

- ↑ Sigmund Freud, On Psychopathology (Middlesex 1987) p. 275

- ↑ Freud, Psychopathology p. 324

- ↑ Otto Fenichel, The Psychoanalytic Theory of Neurosis (London 1946) p. 155

- ↑ Fenichel, Theory pp. 153–4

- ↑ Jean Laplanche and J. B. Pontalis, The Language of Psychoanalysis (London 1988) p. 478

- ↑ Edward Erwin, The Freud encyclopedia (2002) p. 140

- ↑ Melanie Klein, Developments in Psycho-Analysis (London 1989) p. 61

- ↑ Meira Likierman, Melanie Klein: Her Work in Context (2002) p. 167

- ↑ Leslie Sohn, in H. S. Klein/J. Symington eds., Imprisoned Pain and its transformation (London 2000) p. 202

- ↑ Medvec, V.H., Madey, S. F. and Gilouich, T. (1995). When less is more: Counterfactual thinking and satisfaction among Olympic Medalists, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology69, 603–610

- 1 2 3 Fredrickson, B. L., Mancuso, R. A., Branigan, C. and Tugade, M. M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion24, 237–258.

- ↑ Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed., text revision ed.). American Psychiatric Association. p. 808.