Main types

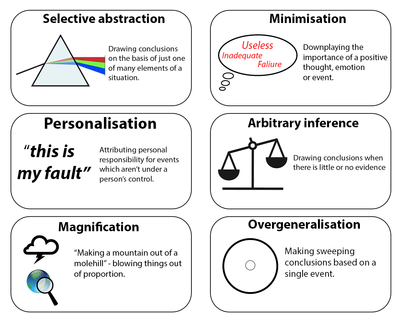

John C. Gibbs and Granville Bud Potter propose four categories for cognitive distortions: self-centered, blaming others, minimizing-mislabeling, and assuming the worst. [16] The cognitive distortions listed below are categories of negative self-talk. [15] [17] [18] [19]

All-or-nothing thinking

The "all-or-nothing thinking distortion" is also referred to as "splitting", [20] "black-and-white thinking", [2] and "polarized thinking." [21] Someone with the all-or-nothing thinking distortion looks at life in black and white categories. [15] Either they are a success or a failure; either they are good or bad; there is no in-between. According to one article, "Because there is always someone who is willing to criticize, this tends to collapse into a tendency for polarized people to view themselves as a total failure. Polarized thinkers have difficulty with the notion of being 'good enough' or a partial success." [20]

- Example (from The Feeling Good Handbook): A woman eats a spoonful of ice cream. She thinks she is a complete failure for breaking her diet. She becomes so depressed that she ends up eating the whole quart of ice cream. [15]

This example captures the polarized nature of this distortion—the person believes they are totally inadequate if they fall short of perfection. In order to combat this distortion, Burns suggests thinking of the world in terms of shades of gray. [15] Rather than viewing herself as a complete failure for eating a spoonful of ice cream, the woman in the example could still recognize her overall effort to diet as at least a partial success.

This distortion is commonly found in perfectionists. [13]

Jumping to conclusions

Reaching preliminary conclusions (usually negative) with little (if any) evidence. Three specific subtypes are identified:[ citation needed ]

Mind reading

Inferring a person's possible or probable (usually negative) thoughts from their behaviour and nonverbal communication; taking precautions against the worst suspected case without asking the person.

- Example 1: A student assumes that the readers of their paper have already made up their minds concerning its topic, and, therefore, writing the paper is a pointless exercise. [19]

- Example 2: Kevin assumes that because he sits alone at lunch, everyone else must think he is a loser. (This can encourage self-fulfilling prophecy; Kevin may not initiate social contact because of his fear that those around him already perceive him negatively). [22]

Fortune-telling

Predicting outcomes (usually negative) of events.

- Example: A depressed person tells themselves they will never improve; they will continue to be depressed for their whole life. [15]

One way to combat this distortion is to ask, "If this is true, does it say more about me or them?" [23]

Labeling

Labelling occurs when someone overgeneralizes the characteristics of other people. Someone might use an unfavourable term to describe a complex person or event, such as assuming that a friend is upset with them due to a late reply to a text message, even though there could be various other reasons for the delay. It is a more extreme form of jumping-to-conclusions cognitive distortion where one presumes to know the thoughts, feelings, or intentions of others without any factual basis.

Emotional reasoning

In the emotional reasoning distortion, it is assumed that feelings expose the true nature of things and experience reality as a reflection of emotionally linked thoughts; something is believed true solely based on a feeling.

Should/shouldn't and must/mustn't statements

Making "must" or "should" statements was included by Albert Ellis in his rational emotive behavior therapy (REBT), an early form of CBT; he termed it "musturbation". Michael C. Graham called it "expecting the world to be different than it is". [25] It can be seen as demanding particular achievements or behaviors regardless of the realistic circumstances of the situation.

- Example: After a performance, a concert pianist believes they should not have made so many mistakes. [24]

- In Feeling Good: The New Mood Therapy, David Burns clearly distinguished between pathological "should statements", moral imperatives, and social norms.

A related cognitive distortion, also present in Ellis' REBT, is a tendency to "awfulize"; to say a future scenario will be awful, rather than to realistically appraise the various negative and positive characteristics of that scenario. According to Burns, "must" and "should" statements are negative because they cause the person to feel guilty and upset at themselves. Some people also direct this distortion at other people, which can cause feelings of anger and frustration when that other person does not do what they should have done. He also mentions how this type of thinking can lead to rebellious thoughts. In other words, trying to whip oneself into doing something with "shoulds" may cause one to desire just the opposite. [15]

Gratitude traps

A gratitude trap is a type of cognitive distortion that typically arises from misunderstandings regarding the nature or practice of gratitude.[ citation needed ] The term can refer to one of two related but distinct thought patterns:

- A self-oriented thought process involving feelings of guilt, shame, or frustration related to one's expectations of how things "should" be.

- An "elusive ugliness in many relationships, a deceptive 'kindness,' the main purpose of which is to make others feel indebted", as defined by psychologist Ellen Kenner. [26]

Personalization and blaming

Personalization is assigning personal blame disproportionate to the level of control a person realistically has in a given situation.

- Example 1: A foster child assumes that they have not been adopted because they are not "loveable enough".

- Example 2: A child has bad grades. Their mother believes it is because they are not a good enough parent. [15]

Blaming is the opposite of personalization. In the blaming distortion, the disproportionate level of blame is placed upon other people, rather than oneself. [15] In this way, the person avoids taking personal responsibility, making way for a "victim mentality".

- Example: Placing blame for marital problems entirely on one's spouse. [15]

Always being right

In this cognitive distortion, being wrong is unthinkable. This distortion is characterized by actively trying to prove one's actions or thoughts to be correct, and sometimes prioritizing self-interest over the feelings of another person. [2] [ unreliable source? ] In this cognitive distortion, the facts that oneself has about their surroundings are always right while other people's opinions and perspectives are wrongly seen. [27] [ unreliable source? ]

Fallacy of change

Relying on social control to obtain cooperative actions from another person. [2] The underlying assumption of this thinking style is that one's happiness depends on the actions of others. The fallacy of change also assumes that other people should change to suit one's own interests automatically, and/or that it is fair to pressure them to change. It may be present in most abusive relationships in which partners' "visions" of each other are tied into the belief that happiness, love, trust, and perfection would just occur once they or the other person change aspects of their beings. [28]

Minimizing-mislabeling

Magnification and minimization

Giving proportionally greater weight to a perceived failure, weakness or threat, or lesser weight to a perceived success, strength or opportunity, so that the weight differs from that assigned by others, such as "making a mountain out of a molehill". In depressed clients, often the positive characteristics of other people are exaggerated, and their negative characteristics are understated.

- Catastrophizing – Giving greater weight to the worst possible outcome, however unlikely, or experiencing a situation as unbearable or impossible when it is just uncomfortable.

Labeling and mislabeling

A form of overgeneralization; attributing a person's actions to their character instead of to an attribute. Rather than assuming the behaviour to be accidental or otherwise extrinsic, one assigns a label to someone or something that is based on the inferred character of that person or thing.

Assuming the worst

Overgeneralizing

Someone who overgeneralizes makes faulty generalizations from insufficient evidence. Such as seeing a "single negative event" as a "never-ending pattern of defeat", [15] and as such drawing a very broad conclusion from a single incident or a single piece of evidence. Even if something bad happens only once, it is expected to happen over and over again. [2]

- Example 1: A person is asked out on a first date, but not a second one. They are distraught as tells a friend, "This always happens to me! I'll never find love!"

- Example 2: A person is lonely and often spends most of their time at home. Friends sometimes ask them to dinner and to meet new people. They feel it is useless to even try. No one could really like them. And anyway, all people are the same: petty and selfish. [24]

One suggestion to combat this distortion is to "examine the evidence" by performing an accurate analysis of one's situation. This aids in avoiding exaggerating one's circumstances. [15]

Disqualifying the positive

Disqualifying the positive refers to rejecting positive experiences by insisting they "don't count" for some reason or other. Negative belief is maintained despite contradiction by everyday experiences. Disqualifying the positive may be the most common fallacy in the cognitive distortion range; it is often analyzed with "always being right", a type of distortion where a person is in an all-or-nothing self-judgment. People in this situation show signs of depression. Examples include:

Mental filtering

Filtering distortions occur when an individual dwells only on the negative details of a situation and filters out the positive aspects. [15]

- Example: Andy gets mostly compliments and positive feedback about a presentation he has done at work, but he also has received a small piece of criticism. For several days following his presentation, Andy dwells on this one negative reaction, forgetting all of the positive reactions that he had also been given. [15]

The Feeling Good Handbook notes that filtering is like a "drop of ink that discolors a beaker of water". [15] One suggestion to combat filtering is a cost–benefit analysis. A person with this distortion may find it helpful to sit down and assess whether filtering out the positive and focusing on the negative is helping or hurting them in the long run. [15]