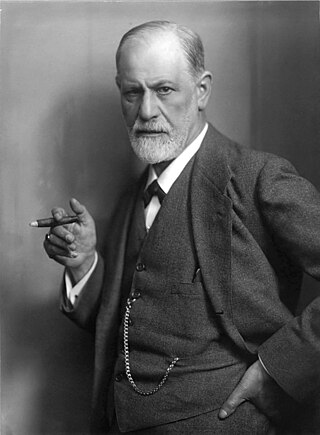

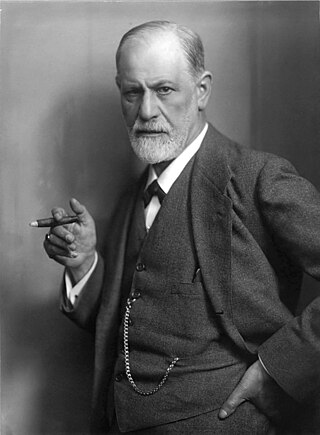

Psychoanalysis is a set of theories and therapeutic techniques that deal in part with the unconscious mind, and which together form a method of treatment for mental disorders. The discipline was established in the early 1890s by Sigmund Freud, whose work stemmed partly from the clinical work of Josef Breuer and others. Freud developed and refined the theory and practice of psychoanalysis until his death in 1939. In an encyclopedic article, he identified the cornerstones of psychoanalysis as "the assumption that there are unconscious mental processes, the recognition of the theory of repression and resistance, the appreciation of the importance of sexuality and of the Oedipus complex." Freud's colleagues Alfred Adler and Carl Gustav Jung developed offshoots of psychoanalysis which they called individual psychology (Adler) and analytical psychology (Jung), although Freud himself wrote a number of criticisms of them and emphatically denied that they were forms of psychoanalysis. Psychoanalysis was later developed in different directions by neo-Freudian thinkers, such as Erich Fromm, Karen Horney, and Harry Stack Sullivan.

In psychoanalytic theory, the id, ego and superego are three distinct, interacting agents in the psychic apparatus, defined in Sigmund Freud's structural model of the psyche. The three agents are theoretical constructs that Freud employed to describe the basic structure of mental life as it was encountered in psychoanalytic practice. Freud himself used the German terms das Es, Ich, and Über-Ich, which literally translate as "the it", "I", and "over-I". The Latin terms id, ego and superego were chosen by his original translators and have remained in use.

Psychoanalytic theory is the theory of personality organization and the dynamics of personality development relating to the practice of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for treating psychopathology. First laid out by Sigmund Freud in the late 19th century, psychoanalytic theory has undergone many refinements since his work. The psychoanalytic theory came to full prominence in the last third of the twentieth century as part of the flow of critical discourse regarding psychological treatments after the 1960s, long after Freud's death in 1939. Freud had ceased his analysis of the brain and his physiological studies and shifted his focus to the study of the psyche, and on treatment using free association and the phenomena of transference. His study emphasized the recognition of childhood events that could influence the mental functioning of adults. His examination of the genetic and then the developmental aspects gave the psychoanalytic theory its characteristics.

Psychology is an academic and applied discipline involving the scientific study of human mental functions and behavior. Occasionally, in addition or opposition to employing the scientific method, it also relies on symbolic interpretation and critical analysis, although these traditions have tended to be less pronounced than in other social sciences, such as sociology. Psychologists study phenomena such as perception, cognition, emotion, personality, behavior, and interpersonal relationships. Some, especially depth psychologists, also study the unconscious mind.

Projection is a psychological phenomenon where feelings directed towards the self are displaced towards other people.

In psychology, sublimation is a mature type of defense mechanism, in which socially unacceptable impulses or idealizations are transformed into socially acceptable actions or behavior, possibly resulting in a long-term conversion of the initial impulse.

In Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, reaction formation is a defense mechanism in which emotions and impulses which are anxiety-producing or perceived to be unacceptable are mastered by exaggeration of the directly opposing tendency. The reaction formations belong to Level 3 of neurotic defense mechanisms, which also include dissociation, displacement, intellectualization, and repression.

In psychology, displacement is an unconscious defence mechanism whereby the mind substitutes either a new aim or a new object for things felt in their original form to be dangerous or unacceptable.

In psychology, introjection is the unconscious adoption of the thoughts or personality traits of others. It occurs as a normal part of development, such as a child taking on parental values and attitudes. It can also be a defense mechanism in situations that arouse anxiety. It has been associated with both normal and pathological development.

Coping refers to conscious strategies used to reduce unpleasant emotions. Coping strategies can be cognitions or behaviors and can be individual or social. To cope is to deal with and overcome struggles and difficulties in life. It is a way for people to maintain their mental and emotional well-being. Everybody has ways of handling difficult events that occur in life, and that is what it means to cope. Coping can be healthy and productive, or destructive and unhealthy. It is recommended that an individual cope in ways that will be beneficial and healthy. "Managing your stress well can help you feel better physically and psychologically and it can impact your ability to perform your best."

Isolation is a defence mechanism in psychoanalytic theory first proposed by Sigmund Freud. While related to repression, the concept distinguishes itself in several ways. It is characterized as a mental process involving the creation of a gap between an unpleasant or threatening cognition, and other thoughts and feelings. By minimizing associative connections with other thoughts, the threatening cognition is remembered less often and is less likely to affect self-esteem or the self concept. Freud illustrated the concept with the example of a person beginning a train of thought and then pausing for a moment before continuing to a different subject. His theory stated that by inserting an interval the person was "letting it be understood symbolically that he will not allow his thoughts about that impression or activity to come into associative contact with other thoughts." As a defense against harmful thoughts, isolation prevents the self from allowing these cognitions to become recurrent and possibly damaging to the self-concept.

Repression is a key concept of psychoanalysis, where it is understood as a defense mechanism that "ensures that what is unacceptable to the conscious mind, and would if recalled arouse anxiety, is prevented from entering into it." According to psychoanalytic theory, repression plays a major role in many mental illnesses, and in the psyche of the average person.

Ego psychology is a school of psychoanalysis rooted in Sigmund Freud's structural id-ego-superego model of the mind.

In psychology, intellectualization (intellectualisation) is a defense mechanism by which reasoning is used to block confrontation with an unconscious conflict and its associated emotional stress – where thinking is used to avoid feeling. It involves emotionally removing one's self from a stressful event. Intellectualization may accompany, but is different from, rationalization, the pseudo-rational justification of irrational acts.

Self-destructive behavior is any behavior that is harmful or potentially harmful towards the person who engages in the behavior.

Splitting is the failure in a person's thinking to bring together the dichotomy of both perceived positive and negative qualities of something into a cohesive, realistic whole. It is a common defense mechanism wherein the individual tends to think in extremes. This kind of dichotomous interpretation is contrasted by an acknowledgement of certain nuances known as "shades of gray".

Stress-related disorders constitute a category of mental disorders. They are maladaptive, biological and psychological responses to short- or long-term exposures to physical or emotional stressors. The National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences categorizes Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) as stress-related disorders. However, the World Health Organization's ICD-11 excludes OCD but categorizes PTSD, Complex Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD), adjustment disorder as stress-related disorders.

Narcissistic defenses are those processes whereby the idealized aspects of the self are preserved, and its limitations denied. They tend to be rigid and totalistic. They are often driven by feelings of shame and guilt, conscious or unconscious.

Sigmund Freud is considered to be the founder of the psychodynamic approach to psychology, which looks to unconscious drives to explain human behavior. Freud believed that the mind is responsible for both conscious and unconscious decisions that it makes on the basis of psychological drives. The id, ego, and super-ego are three aspects of the mind Freud believed to comprise a person's personality. Freud believed people are "simply actors in the drama of [their] own minds, pushed by desire, pulled by coincidence. Underneath the surface, our personalities represent the power struggle going on deep within us".

Denial or abnegation is a psychological defense mechanism postulated by psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, in which a person is faced with a fact that is too uncomfortable to accept and rejects it instead, insisting that it is not true despite what may be overwhelming evidence.