Related Research Articles

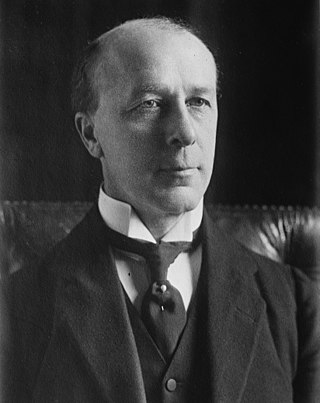

Edward Grey, 1st Viscount Grey of Fallodon,, better known as Sir Edward Grey, was a British Liberal statesman and the main force behind British foreign policy in the era of the First World War.

The Agadir Crisis, Agadir Incident, or Second Moroccan Crisis was a brief crisis sparked by the deployment of a substantial force of French troops in the interior of Morocco in April 1911 and the deployment of the German gunboat SMS Panther to Agadir, a Moroccan Atlantic port. Germany did not object to France's expansion but wanted territorial compensation for itself. Berlin threatened warfare, sent a gunboat, and stirred up German nationalists. Negotiations between Berlin and Paris resolved the crisis on 4 November 1911: France took over Morocco as a protectorate in exchange for territorial concessions to German Cameroon from the French Congo.

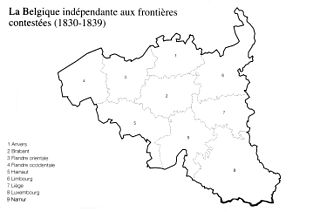

The Treaty of London of 1839, was signed on 19 April 1839 between the Concert of Europe, the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Kingdom of Belgium. It was a direct follow-up to the 1831 Treaty of the XVIII Articles, which the Netherlands had refused to sign, and the result of negotiations at the London Conference of 1838–1839.

The Soviet–Japanese Neutrality Pact, also known as the Japanese–Soviet Non-aggression Pact, was a non-aggression pact between the Soviet Union and the Empire of Japan signed on April 13, 1941, two years after the conclusion of the Soviet-Japanese Border War. The agreement meant that for most of World War II, the two nations fought against each other's allies but not against each other. In 1945, late in the war, the Soviets scrapped the pact and joined the Allied campaign against Japan.

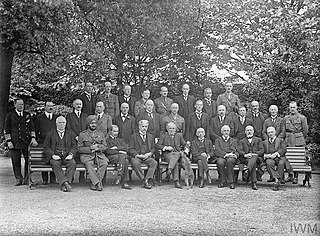

A war cabinet is a committee formed by a government in a time of war to efficiently and effectively conduct that war. It is usually a subset of the full executive cabinet of ministers, although it is quite common for a war cabinet to have senior military officers and opposition politicians as members.

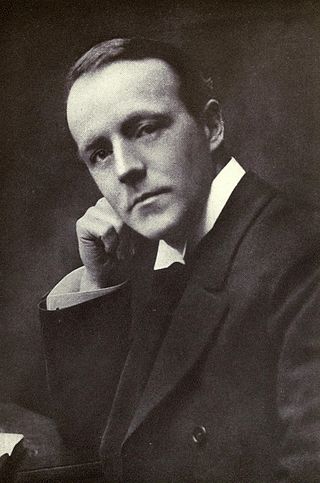

Reginald McKenna was a British banker and Liberal politician. His first Cabinet post under Henry Campbell-Bannerman was as President of the Board of Education, after which he served as First Lord of the Admiralty. His most important roles were as Home Secretary and Chancellor of the Exchequer during the premiership of H. H. Asquith. He was studious and meticulous, noted for his attention to detail, but also for being bureaucratic and partisan.

Walter Runciman, 1st Viscount Runciman of Doxford, was a prominent Liberal and later National Liberal politician in the United Kingdom. His 1938 diplomatic mission to Czechoslovakia was key to the enactment of the British policy of appeasement of Nazi Germany preceding the Second World War.

Liberal David Lloyd George formed a coalition government in the United Kingdom in December 1916, and was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by King George V. It replaced the earlier wartime coalition under H. H. Asquith, which had been held responsible for losses during the Great War. Those Liberals who continued to support Asquith served as the Official Opposition. The government continued in power after the end of the war in 1918, though Lloyd George was increasingly reliant on the Conservatives for support. After several scandals including allegations of the sale of honours, the Conservatives withdrew their support after a meeting at the Carlton Club in 1922, and Bonar Law formed a government.

The Chanak Crisis, also called the Chanak Affair and the Chanak Incident, was a war scare in September 1922 between the United Kingdom and the Government of the Grand National Assembly in Turkey. Chanak refers to Çanakkale, a city on the Anatolian side of the Dardanelles Strait. The crisis was caused by Turkish efforts to push the Greek armies out of Turkey and restore Turkish rule in the Allied-occupied territories, primarily in Constantinople and Eastern Thrace. Turkish troops marched against British and French positions in the Dardanelles neutral zone. For a time, war between Britain and Turkey seemed possible, but Canada refused to agree as did France and Italy. British public opinion did not want a war. The British military did not either, and the top general on the scene, Sir Charles Harington, refused to relay an ultimatum to the Turks because he counted on a negotiated settlement. The Conservatives in Britain's coalition government refused to follow Liberal Prime Minister David Lloyd George, who with Winston Churchill was calling for war.

The July Crisis was a series of interrelated diplomatic and military escalations among the major powers of Europe in the summer of 1914, which led to the outbreak of World War I. The crisis began on 28 June 1914, when Gavrilo Princip, a Bosnian Serb nationalist, assassinated Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, and his wife Sophie, Duchess of Hohenberg. A complex web of alliances, coupled with the miscalculations of numerous political and military leaders, resulted in an outbreak of hostilities amongst most of the major European nations by early August 1914.

The Allies, formally referred to as the United Nations from 1942, were an international military coalition formed during World War II (1939–1945) to oppose the Axis powers, led by Nazi Germany, the Empire of Japan, and the Kingdom of Italy. Its principal members by the end of 1941 were the "Big Four" - United Kingdom, United States, Soviet Union, and China.

The Allies, or the Entente Powers, were an international military coalition of countries led by France, the United Kingdom, Russia, the United States, Italy, and Japan against the Central Powers of Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire, and Bulgaria in World War I (1914–1918).

The government of the United Kingdom declared war on the Empire of Japan on 8 December 1941, following the Japanese attacks on British Malaya, Singapore, and Hong Kong on the previous day as well as in response to the bombing of the US fleet at Pearl Harbor.

The Churchill war ministry was the United Kingdom's coalition government for most of the Second World War from 10 May 1940 to 23 May 1945. It was led by Winston Churchill, who was appointed Prime Minister of the United Kingdom by King George VI following the resignation of Neville Chamberlain in the aftermath of the Norway Debate.

The Liberal government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland that began in 1905 and ended in 1915 consisted of two ministries: the first led by Henry Campbell-Bannerman and the final three by H. H. Asquith.

This article documents the career of Winston Churchill in Parliament from its beginning in 1900 to the start of his term as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in World War II.

This is a timeline of the British home front during the First World War from 1914 to 1918. This conflict was the first modern example of total war in the United Kingdom; innovations included the mobilisation of the workforce, including many women, for munitions production, conscription and rationing. Civilians were subjected to naval bombardments, strategic bombing and food shortages caused by a submarine blockade.

The first Luther cabinet, headed by the political independent Hans Luther, was the 12th democratically elected government of the Weimar Republic. It took office on 15 January 1925, replacing the second cabinet of Wilhelm Marx, which had resigned when Marx was unable to form a new coalition following the December 1924 Reichstag election. Luther's cabinet was made up of a loose coalition of five parties ranging from the German Democratic Party (DDP) on the left to the German National People's Party (DNVP) on the right.

The United Kingdom entered World War I on 4 August 1914, when King George V declared war after the expiry of an ultimatum to the German Empire. The official explanation focused on protecting Belgium as a neutral country; the main reason, however, was to prevent a French defeat that would have left Germany in control of Western Europe. The Liberal Party was in power with prime minister H. H. Asquith and foreign minister Edward Grey leading the way. The Liberal cabinet made the decision, although the party had been strongly anti-war until the last minute. The Conservative Party was pro-war. The Liberals knew that if they split on the war issue, they would lose control of the government to the Conservatives.

The Declaration of Sainte-Adresse was a diplomatic announcement made on 14 February 1916 by the principal Allied powers of the First World War. It was also supported by Italy and Japan. The declaration stated that the powers would refuse to sign any peace treaty ending the war that left Belgium, a neutral power at the war's start, without "political and economic independence". It was extended in April 1916 to also cover the Belgian Congo.

References

- ↑ Cook, Chris; Stevenson, John (2005). The Routledge Companion to European History since 1763. Routledge. p. 121. ISBN 9780415345835.

- ↑ Why did Britain go to War?, The National Archives, retrieved 30 April 2016

- ↑ Christopher Clark, The Sleepwalkers (2012) p. 539.

- ↑ Isabel V. Hull, A Scrap of Paper: Breaking and Making International Law during the Great War (Cornell UP, 2014) p, 33

- ↑ Steve Watters, Where Britain goes, we go?, Government of New Zealand, 9 January 2014, accessed 13 November 2021

- ↑ "GERMANY AND BELGIUM".

- ↑ "VIOLATION OF BELGIAN NEUTRALITY".

- ↑ "Belgian Neutrality Violated by Germany".

- ↑ Churchill, Winston S. (1938). "X: The Mobiliization of the Navy". The World Crisis 1911-1918 . Vol. 1 (New ed.). London: Odhams Press Limited. p. 186.

- ↑ Douglas Newton, The Darkest Days: the truth behind Britain's rush to war, 1914 (London and New York: Verso, 2014, ISBN 9781781683507), pp. 279, 364