A crossbow is a ranged weapon using an elastic launching device consisting of a bow-like assembly called a prod, mounted horizontally on a main frame called a tiller, which is hand-held in a similar fashion to the stock of a long gun. Crossbows shoot arrow-like projectiles called bolts or quarrels. A person who shoots crossbow is called a crossbowman or an arbalist.

Medieval warfare is the warfare of the Middle Ages. Technological, cultural, and social advancements had forced a severe transformation in the character of warfare from antiquity, changing military tactics and the role of cavalry and artillery. In terms of fortification, the Middle Ages saw the emergence of the castle in Europe, which then spread to the Holy Land.

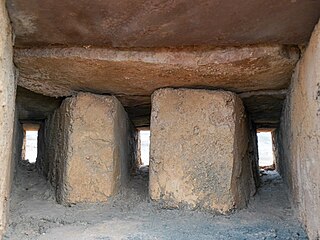

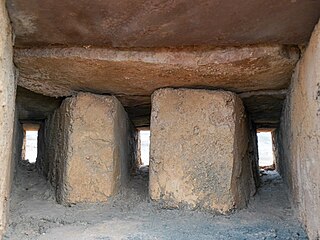

Medieval fortification refers to medieval military methods that cover the development of fortification construction and use in Europe, roughly from the fall of the Western Roman Empire to the Renaissance. During this millennium, fortifications changed warfare, and in turn were modified to suit new tactics, weapons and siege techniques.

A Roman siege tower or breaching tower is a specialized siege engine, constructed to protect assailants and ladders while approaching the defensive walls of a fortification. The tower was often rectangular with four wheels with its height roughly equal to that of the wall or sometimes higher to allow archers or crossbowmen to stand on top of the tower and shoot arrows or quarrels into the fortification. Because the towers were wooden and thus flammable, they had to have some non-flammable covering of iron or fresh animal skins.

A castle is a type of fortified structure built during the Middle Ages predominantly by the nobility or royalty and by military orders. Scholars usually consider a castle to be the private fortified residence of a lord or noble. This is distinct from a mansion, palace and villa, whose main purpose was exclusively for pleasance and are not primarily fortresses but may be fortified. Use of the term has varied over time and, sometimes, has also been applied to structures such as hill forts and 19th- and 20th-century homes built to resemble castles. Over the Middle Ages, when genuine castles were built, they took on a great many forms with many different features, although some, such as curtain walls, arrowslits, and portcullises, were commonplace.

An arquebus is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

White Castle, also known historically as Llantilio Castle, is a ruined castle near the village of Llantilio Crossenny in Monmouthshire, Wales. The fortification was established by the Normans in the wake of the invasion of England in 1066, to protect the route from Wales to Hereford. Possibly commissioned by William fitz Osbern, the Earl of Hereford, it comprised three large earthworks with timber defences. In 1135, a major Welsh revolt took place and in response King Stephen brought together White Castle and its sister fortifications of Grosmont and Skenfrith to form a lordship known as the "Three Castles", which continued to play a role in defending the region from Welsh attack for several centuries.

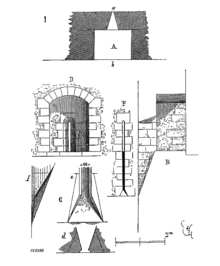

A merlon is the solid upright section of a battlement in medieval architecture or fortifications. Merlons are sometimes pierced by narrow, vertical embrasures or slits designed for observation and fire. The space between two merlons is called a crenel, and a succession of merlons and crenels is a crenellation. Crenels designed in later eras for use by cannons were also called embrasures.

An embrasure is the opening in a battlement between two raised solid portions (merlons). Alternatively, an embrasure can be a space hollowed out throughout the thickness of a wall by the establishment of a bay. This term designates the internal part of this space, relative to the closing device, door or window. In fortification this refers to the outward splay of a window or of an arrowslit on the inside.

A battlement, in defensive architecture, such as that of city walls or castles, comprises a parapet, in which gaps or indentations, which are often rectangular, occur at intervals to allow for the launch of arrows or other projectiles from within the defences. These gaps are termed embrasures, also known as crenels or crenelles, and a wall or building with them is described as crenellated; alternative older terms are castellated and embattled. The act of adding crenels to a previously unbroken parapet is termed crenellation.

Early thermal weapons, which used heat or burning action to destroy or damage enemy personnel, fortifications or territories, were employed in warfare during the classical and medieval periods.

Château Gaillard is a medieval castle ruin overlooking the River Seine above the commune of Les Andelys, in the French department of Eure, in Normandy. It is located some 95 kilometres (59 mi) north-west of Paris and 40 kilometres (25 mi) from Rouen. Construction began in 1196 under the auspices of Richard the Lionheart, who was simultaneously King of England and feudal Duke of Normandy. The castle was expensive to build, but the majority of the work was done in an unusually short period of time. It took just two years and, at the same time, the town of Petit Andely was constructed. Château Gaillard has a complex and advanced design, and uses early principles of concentric fortification; it was also one of the earliest European castles to use machicolations. The castle consists of three enclosures separated by dry moats, with a keep in the inner enclosure.

Kantara Castle is a castle in Cyprus. The exact date of its construction remains unknown, the most plausible theory being the Byzantine period. It combines Byzantine and Frankish architectural elements, became derelict in 1525 and was dismantled in 1560. It gave its name to the nearby Kantara monastery.

It is not clear where and when the crossbow originated, but it is believed to have appeared in China and Europe around the 7th to 5th centuries BC. In China the crossbow was one of the primary military weapons from the Warring States period until the end of the Han dynasty, when armies were composed of up to 30 to 50 percent crossbowmen. The crossbow lost much of its popularity after the fall of the Han dynasty, likely due to the rise of the more resilient heavy cavalry during the Six Dynasties. One Tang dynasty source recommends a bow to crossbow ratio of five to one as well as the utilization of the countermarch to make up for the crossbow's lack of speed. The crossbow countermarch technique was further refined in the Song dynasty, but crossbow usage in the military continued to decline after the Mongol conquest of China. Although the crossbow never regained the prominence it once had under the Han, it was never completely phased out either. Even as late as the 17th century AD, military theorists were still recommending it for wider military adoption, but production had already shifted in favour of firearms and traditional composite bows.

A loophole is an ambiguity or inadequacy in a system, such as a law or security, which can be used to circumvent or otherwise avoid the purpose, implied or explicitly stated, of the system.

Despite the rise of knightly cavalry in the 11th century, infantry played an important role throughout the Middle Ages on both the battlefield and in sieges. From the 14th century onwards, it has been argued that there was a rise in the prominence of infantry forces, sometimes referred to as an "infantry revolution", but this view is strongly contested by some military historians.

An arbalist, also spelled arbelist, is one who shoots a crossbow.

A curtain wall is a defensive wall between fortified towers or bastions of a castle, fortress, or town.

In fortification architecture, a rampart is a length of embankment or wall forming part of the defensive boundary of a castle, hillfort, settlement or other fortified site. It is usually broad-topped and made of excavated earth and/or masonry.

A loophole is a protected small opening, which allows a firearm to be aimed and discharged, while providing cover and concealment for the rifleman. To prevent detection, the rifle's muzzle should not protrude through the loophole, particularly at night to hide the muzzle flash.