The history of ancient Israel and Judah spans from the early appearance of the Israelites in Canaan's hill country during the late second millenium BCE, to the establishment and subsequent downfall of the two Israelite kingdoms in the mid-first millenium BCE. This history unfolds within the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. The earliest documented mention of "Israel" as a people appears on the Merneptah Stele, an ancient Egyptian inscription dating back to around 1208 BCE. Archaeological evidence suggests that ancient Israelite culture evolved from the pre-existing Canaanite civilization. During the Iron Age II period, two Israelite kingdoms emerged in the region: the Kingdom of Israel in the north and the Kingdom of Judah in the south.

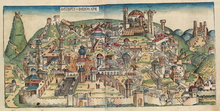

The Kingdom of Judah was an Israelite kingdom of the Southern Levant during the Iron Age. Centered in the highlands of Judea, the landlocked kingdom's capital was Jerusalem. Jews are named after Judah, and primarily descend from people who lived in the region.

Zedekiah was the twentieth and final King of Judah before the conquest of the kingdom by Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon. His birth name was Mattaniah/Mattanyahu.

Jeconiah, also known as Coniah and as Jehoiachin, was the nineteenth and penultimate king of Judah who was dethroned by the King of Babylon, Nebuchadnezzar II in the 6th century BCE and was taken into captivity. He was the son and successor of King Jehoiakim, and the grandson of King Josiah. Most of what is known about Jeconiah is found in the Hebrew Bible. Records of Jeconiah's existence have been found in Iraq, such as the Jehoiachin's Rations Tablets. These tablets were excavated near the Ishtar Gate in Babylon and have been dated to c. 592 BCE. Written in cuneiform, they mention Jeconiah and his five sons as recipients of food rations in Babylon.

Jehoiakim, also sometimes spelled Jehoikim was the eighteenth and antepenultimate King of Judah from 609 to 598 BC. He was the second son of King Josiah and Zebidah, the daughter of Pedaiah of Rumah. His birth name was Eliakim.

The Kings of Judah were the monarchs who ruled over the ancient Kingdom of Judah, which was formed in about 930 BCE, according to the Hebrew Bible, when the United Kingdom of Israel split, with the people of the northern Kingdom of Israel rejecting Rehoboam as their monarch, leaving him as solely the King of Judah.

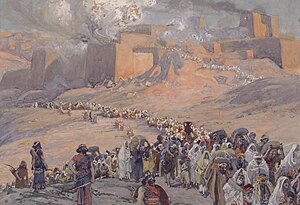

The siege of Jerusalem was the final event of the Judahite revolts against Babylon, in which Nebuchadnezzar II, king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, besieged Jerusalem, the capital city of the Kingdom of Judah. Jerusalem fell after a 30-month siege, following which the Babylonians systematically destroyed the city and Solomon's Temple. The Kingdom of Judah was dissolved and many of its inhabitants were exiled to Babylon.

The return to Zion is an event recorded in Ezra–Nehemiah of the Hebrew Bible, in which the Jews of the Kingdom of Judah—subjugated by the Neo-Babylonian Empire—were freed from the Babylonian captivity following the Persian conquest of Babylon. In 539 BCE, the Persian king Cyrus the Great issued the Edict of Cyrus allowing the Jews to return to Jerusalem and the Land of Judah, which was made a self-governing Jewish province under the new Persian Empire.

The siege of Jerusalem was a military campaign carried out by Nebuchadnezzar II, king of the Neo-Babylonian Empire, in which he besieged Jerusalem, then capital of the Kingdom of Judah. The city surrendered, and its king Jeconiah was deported to Babylon and replaced by his Babylonian-appointed uncle, Zedekiah. The siege is recorded in both the Hebrew Bible and the Babylonian Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle.

The origins of Judaism lie in Bronze Age polytheistic Canaanite religion. Judaism also syncretized elements of other Semitic religions such as Babylonian religion, which is reflected in the early prophetic books of the Hebrew Bible.

Yehud Medinata, also called Yehud Medinta or simply Yehud, was an autonomous administrative division of the Achaemenid Persian Empire. It constituted a part of Eber-Nari and was bounded by Arabia to the south, lying along the frontier of the two satrapies. Spanning most of Judea—from the Shephelah in the west to the Dead Sea in the east—it was one of several Persian provinces in Palestine, together with Moab, Ammon, Gilead, Samaria, Ashdod, and Idumea, among others. It existed for just over two centuries before the Greek conquest of Persia resulted in it being incorporated into the Hellenistic empires.

Yehud was a province of the Neo-Babylonian Empire established in the former territories of the Kingdom of Judah, which was destroyed by the Babylonians in the aftermath of the Judahite revolts and the siege of Jerusalem in 587/6 BCE. It first existed as a Jewish administrative division under Gedaliah ben Aḥikam, who was later assassinated by a fellow Jew. The Fast of Gedaliah, a minor fast day in Judaism, was established in memory of this event, and is lamented by observant Jews even to this day.

Judah's revolts against Babylon were attempts by the Kingdom of Judah to escape dominance by the Neo-Babylonian Empire. Resulting in a Babylonian victory and the destruction of the Kingdom of Judah, it marked the beginning of the prolonged hiatus in Jewish self-rule in Judaea until the Maccabean Revolt of the 2nd century BCE. Babylonian forces captured the capital city of Jerusalem and destroyed Solomon's Temple, completing the fall of Judah, an event which marked the beginning of the Babylonian captivity, a period in Jewish history in which a large number of Judeans were forcibly removed from Judah and resettled in Mesopotamia.

The Nebuchadnezzar Chronicle, also known as Jerusalem Chronicle, is one of the series of Babylonian Chronicles, and contains a description of the first eleven years of the reign of Nebuchadnezzar II. The tablet details Nebuchadnezzar's military campaigns in the west and has been interpreted to refer to both the Battle of Carchemish and the Siege of Jerusalem. The tablet is numbered ABC5 in Grayson's standard text and BM 21946 in the British Museum.

The Al-Yahudu tablets are a collection of about 200 clay tablets from the sixth and fifth centuries BCE on the exiled Judean community in Babylonia following the destruction of the First Temple. They contain information on the physical condition of the exiles from Judah and their financial condition in Babylon. The tablets are named after the central settlement mentioned in the documents, āl Yahudu, which was "presumably in the vicinity of Borsippa".

2 Kings 24 is the twenty-fourth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. This chapter records the events during the reigns of Jehoiakim, Jehoiachin and Zedekiah, kings of Judah.

2 Chronicles 36 is the thirty-sixth chapter of the Second Book of Chronicles the Old Testament of the Christian Bible or of the second part of the Books of Chronicles in the Hebrew Bible. The book is compiled from older sources by an unknown person or group, designated by modern scholars as "the Chronicler", and had the final shape established in late fifth or fourth century BCE. This chapter belongs to the section focusing on the kingdom of Judah until its destruction by the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar and the beginning of restoration under Cyrus the Great of Persia. It contains the regnal accounts of the last four kings of Judah - Jehoahaz, Jehoiakim, Jehoiachin and Zedekiah - and the edict of Cyrus allowing the exiled Jews to return to Jerusalem.

Jeremiah 22 is the twenty-second chapter of the Book of Jeremiah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. This book contains prophecies attributed to the prophet Jeremiah, and is one of the Books of the Prophets.

Jeremiah 24 is the twenty-fourth chapter of the Book of Jeremiah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. This book contains prophecies attributed to the prophet Jeremiah, and is one of the Books of the Prophets. This chapter concerns Jeremiah's vision of two baskets of figs.