Deamination is the removal of an amino group from a molecule. Enzymes that catalyse this reaction are called deaminases.

The CpG sites or CG sites are regions of DNA where a cytosine nucleotide is followed by a guanine nucleotide in the linear sequence of bases along its 5' → 3' direction. CpG sites occur with high frequency in genomic regions called CpG islands.

DNA repair is a collection of processes by which a cell identifies and corrects damage to the DNA molecules that encodes its genome. In human cells, both normal metabolic activities and environmental factors such as radiation can cause DNA damage, resulting in tens of thousands of individual molecular lesions per cell per day. Many of these lesions cause structural damage to the DNA molecule and can alter or eliminate the cell's ability to transcribe the gene that the affected DNA encodes. Other lesions induce potentially harmful mutations in the cell's genome, which affect the survival of its daughter cells after it undergoes mitosis. As a consequence, the DNA repair process is constantly active as it responds to damage in the DNA structure. When normal repair processes fail, and when cellular apoptosis does not occur, irreparable DNA damage may occur. This can eventually lead to malignant tumors, or cancer as per the two-hit hypothesis.

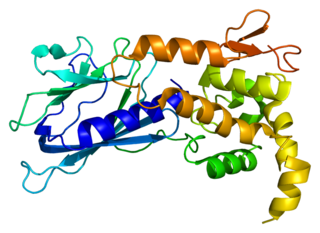

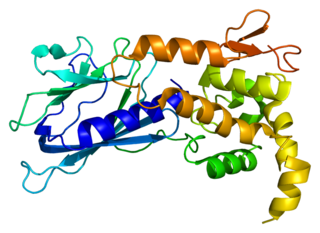

DNA glycosylases are a family of enzymes involved in base excision repair, classified under EC number EC 3.2.2. Base excision repair is the mechanism by which damaged bases in DNA are removed and replaced. DNA glycosylases catalyze the first step of this process. They remove the damaged nitrogenous base while leaving the sugar-phosphate backbone intact, creating an apurinic/apyrimidinic site, commonly referred to as an AP site. This is accomplished by flipping the damaged base out of the double helix followed by cleavage of the N-glycosidic bond.

Nucleotide excision repair is a DNA repair mechanism. DNA damage occurs constantly because of chemicals, radiation and other mutagens. Three excision repair pathways exist to repair single stranded DNA damage: Nucleotide excision repair (NER), base excision repair (BER), and DNA mismatch repair (MMR). While the BER pathway can recognize specific non-bulky lesions in DNA, it can correct only damaged bases that are removed by specific glycosylases. Similarly, the MMR pathway only targets mismatched Watson-Crick base pairs.

In biochemistry and molecular genetics, an AP site, also known as an abasic site, is a location in DNA that has neither a purine nor a pyrimidine base, either spontaneously or due to DNA damage. It has been estimated that under physiological conditions 10,000 apurinic sites and 500 apyrimidinic may be generated in a cell daily.

MUTYH is a human gene that encodes a DNA glycosylase, MUTYH glycosylase. It is involved in oxidative DNA damage repair and is part of the base excision repair pathway. The enzyme excises adenine bases from the DNA backbone at sites where adenine is inappropriately paired with guanine, cytosine, or 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanine, a common form of oxidative DNA damage.

Werner syndrome ATP-dependent helicase, also known as DNA helicase, RecQ-like type 3, is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the WRN gene. WRN is a member of the RecQ Helicase family. Helicase enzymes generally unwind and separate double-stranded DNA. These activities are necessary before DNA can be copied in preparation for cell division. Helicase enzymes are also critical for making a blueprint of a gene for protein production, a process called transcription. Further evidence suggests that Werner protein plays a critical role in repairing DNA. Overall, this protein helps maintain the structure and integrity of a person's DNA.

DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) lyase is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the APEX1 gene.

DNA ligase 1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the LIG1 gene. DNA ligase I is the only known eukaryotic DNA ligase involved in both DNA replication and repair, making it the most studied of the ligases.

The enzyme DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) lyase, also referred to as DNA-(apurinic or apyrimidinic site) 5'-phosphomonoester-lyase or DNA AP lyase catalyzes the cleavage of the C-O-P bond 3' from the apurinic or apyrimidinic site in DNA via β-elimination reaction, leaving a 3'-terminal unsaturated sugar and a product with a terminal 5'-phosphate. In the 1970s, this class of enzyme was found to repair at apurinic or apyrimidinic DNA sites in E. coli and in mammalian cells. The major active enzyme of this class in bacteria, and specifically, E. coli is endonuclease type III. This enzyme is part of a family of lyases that cleave carbon-oxygen bonds.

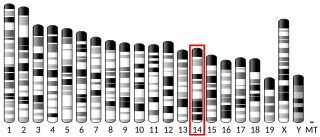

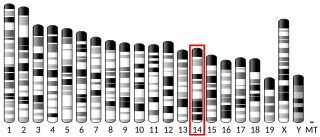

DNA excision repair protein ERCC-6 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the ERCC6 gene. The ERCC6 gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 10 at position 11.23.

DNA-3-methyladenine glycosylase also known as 3-alkyladenine DNA glycosylase (AAG) or N-methylpurine DNA glycosylase (MPG) is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the MPG gene.

Endonuclease III-like protein 1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the NTHL1 gene.

Endonuclease VIII-like 1 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the NEIL1 gene.

Methyl-CpG-binding domain protein 4 is a protein that in humans is encoded by the MBD4 gene.

Endonuclease VIII-like 2 is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the NEIL2 gene.

For molecular biology in mammals, DNA demethylation causes replacement of 5-methylcytosine (5mC) in a DNA sequence by cytosine (C). DNA demethylation can occur by an active process at the site of a 5mC in a DNA sequence or, in replicating cells, by preventing addition of methyl groups to DNA so that the replicated DNA will largely have cytosine in the DNA sequence.

In molecular biology, the H2TH domain is a DNA-binding domain found in DNA glycosylase/AP lyase enzymes, which are involved in base excision repair of DNA damaged by oxidation or by mutagenic agents. Most damage to bases in DNA is repaired by the base excision repair pathway. These enzymes are primarily from bacteria, and have both DNA glycosylase activity EC 3.2.2.- and AP lyase activity EC 4.2.99.18. Examples include formamidopyrimidine-DNA glycosylases and endonuclease VIII (Nei).

DNA-deoxyinosine glycosylase is an enzyme with systematic name DNA-deoxyinosine deoxyribohydrolase. This enzyme is involved in DNA damage repair and targets hypoxanthine bases.