Lesotho, formally the Kingdom of Lesotho, is a landlocked country in Southern Africa. As an enclave of South Africa, with which it shares a 1,106 km border, it is the only sovereign enclave in the world outside of the Italian Peninsula. It is situated in the Maloti Mountains and contains the highest peak in Southern Africa. It has an area of over 30,000 km2 (11,600 sq mi) and has a population of about 2 million. Its capital and largest city is Maseru.

The history of people living in the area now known as Lesotho goes back as many as 400 years. Present Lesotho emerged as a single polity under King Moshoeshoe I in 1822. Under Moshoeshoe I, Basotho joined other clans in their struggle against the Lifaqane associated with famine and the reign of Shaka Zulu from 1818 to 1828.

Lesotho is a mountainous, landlocked country located in Southern Africa. It is an enclave, surrounded by South Africa. The total length of the country's borders is 909 kilometres (565 mi). Lesotho covers an area of around 30,355 square kilometres (11,720 sq mi), of which a negligible percentage is covered with water.

Politics of Lesotho takes place in a framework of a parliamentary representative democratic constitutional monarchy, whereby the Prime Minister of Lesotho is the head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the two chambers of Parliament, the Senate and the National Assembly. The Judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature.

The Orange Free State was an independent Boer sovereign republic under British suzerainty in Southern Africa during the second half of the 19th century, which ceased to exist after it was defeated and surrendered to the British Empire at the end of the Second Boer War in 1902. It is one of the three historical precursors to the present-day Free State province.

The Sotho, also known as the Basotho, are a prominent Sotho-Tswana ethnic group native to Southern Africa. They primarily inhabit the regions of Lesotho and South Africa.

Moshoeshoe I was the first king of Lesotho. He was the first son of Mokhachane, a minor chief of the Bamokoteli lineage, a branch of the Koena (crocodile) clan. In his youth, he helped his father gain power over some other smaller clans. At the age of 34 Moshoeshoe formed his own clan and became a chief. He and his followers settled at the Butha-Buthe Mountain. He became the first and longest-serving King of Lesotho in 1822.

Mohale's Hoek is a district of Lesotho. Mohale's Hoek is the capital city or camptown, and only town in the district. In the southwest, Mohale's Hoek borders on South Africa, while domestically, it borders on Mafeteng District in northwest, Maseru District in north, Thaba-Tseka District in northeast, Qacha's Nek District in east, and Quthing District in southeast.

The Basuto Gun War, also known as the Basutoland Rebellion, was a conflict between the Basuto and the British Cape Colony. It lasted from 13 September 1880 to 29 April 1881 and ended in a Basuto victory.

Smithfield is a small town in the Free State province of South Africa. Founded in 1848 in the Orange River Sovereignty, the town is situated in a rural farming district and is the third oldest town in present-day Free State, after Philippolis and Winburg.

The Free State–Basotho Wars refers to a series of wars fought between King Moshoeshoe I, the ruler of the Basotho Kingdom, and white settlers, in what is now known as the Free State. These can be divided into the Senekal's War of 1858, the Seqiti War in 1865−1866 and the Third Basotho War in 1867−68.

Sir Thomas Charles Scanlen was a politician and administrator of the Cape Colony.

'Mantšebo was the ruler of Basutoland from 1941 to 1960, as the regent for her stepson, the future Moshoeshoe II.

Administratively, Lesotho is divided into ten districts, each headed by a district administrator. Each district has a capital known as a camptown.

The border between Lesotho and South Africa is 909 kilometres (565 mi) long and forms a complete loop, as Lesotho is an enclave entirely surrounded by South Africa. The border follows the Caledon River, the drainage divide of the Drakensberg mountains, the Orange River, the Makhaleng River, and a series of hills joining the Makhaleng back to the Caledon.

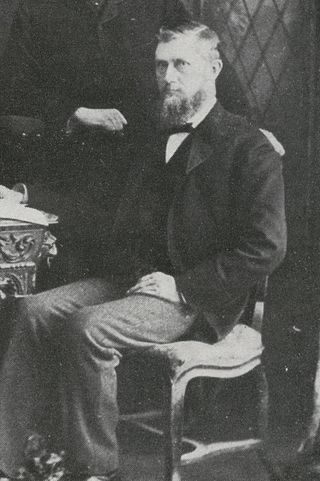

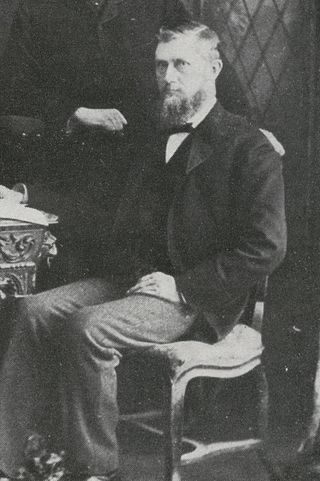

Lieutenant-Colonel Sir Marshal James Clarke was a British colonial administrator and an officer of the Royal Artillery. He was the first Resident Commissioner in Basutoland from 1884 to 1893; Resident Commissioner in Zululand from 1893 to 1898; and, following the botched Jameson Raid, the first Resident Commissioner in Southern Rhodesia from 1898 to 1905.

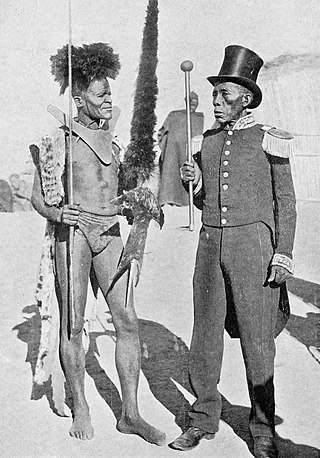

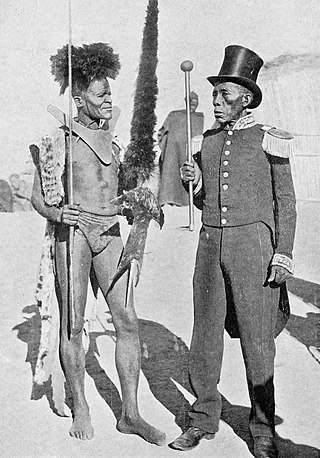

Morosi was a Baphuthi chief in the wild southern part of Basutoland. He led a revolt against the Cape Colony government in 1879, in defence of his independence south of the Orange River. The British refused to help the Cape Government. However, Letsie, the paramount chief and first son of Moshoeshoe, and many of the Sotho ruling establishment, rallied to support the Cape forces, and the rebellion was put down after several months of arduous fighting. Morosi was beheaded and his body mutilated by Cape troops.

Basotho nationality law is regulated by the Constitution of Lesotho, as amended; the Lesotho Citizenship Order, and its revisions; the 1983 Refugees Act; and various international agreements to which the country is a signatory. These laws determine who is, or is eligible to be, a national of Lesotho. The legal means to acquire nationality, formal legal membership in a nation, differ from the domestic relationship of rights and obligations between a national and the nation, known as citizenship. Nationality describes the relationship of an individual to the state under international law, whereas citizenship is the domestic relationship of an individual within the nation. In Britain and thus the Commonwealth of Nations, though the terms are often used synonymously outside of law, they are governed by different statutes and regulated by different authorities. Basotho nationality is typically obtained under the principle of jus soli, born in Lesotho, or jus sanguinis, i.e. by birth in Lesotho or abroad to parents with Basotho nationality. It can be granted to persons with an affiliation to the country, or to a permanent resident who has lived in the country for a given period of time through naturalisation.

Masopha was a chief of the Basuto people. He was the third son of Basuto paramount chief Moshoeshoe I. During his youth he fought in numerous conflicts against neighboring tribes and European colonists, distinguishing himself for his bravery. Following the incorporation of Basutoland into the Cape Colony, Masopha resisted the imposition of colonial rule and emerged as one of the most powerful Basuto chiefs. In 1880, he became one of the leaders of Basuto resistance to the Cape in the Basuto Gun War. Following the end of the war he came into conflict with his nephew and heir apparent Lerotholi. The two clashed in a brief civil war in January 1898. Masopha was defeated and died in obscurity in July 1898.