The Bible is a collection of religious texts or scriptures, some, all, or a variant of which are held to be sacred in Christianity, Judaism, Samaritanism, Islam, the Baha'i Faith, and other Abrahamic religions. The Bible is an anthology originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Koine Greek. These texts include instructions, stories, poetry, and prophecies, among other genres. The collection of materials that are accepted as part of the Bible by a particular religious tradition or community is called a biblical canon. Believers in the Bible generally consider it to be a product of divine inspiration, but the way they understand what that means and interpret the text varies.

Samaritanism is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion. It comprises the collective spiritual, cultural, and legal traditions of the Samaritan people, who originate from the Hebrews and Israelites and began to emerge as a relatively distinct group after the Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire during the Iron Age. Central to the faith is the Samaritan Pentateuch, which Samaritans believe is the original and unchanged version of the Torah.

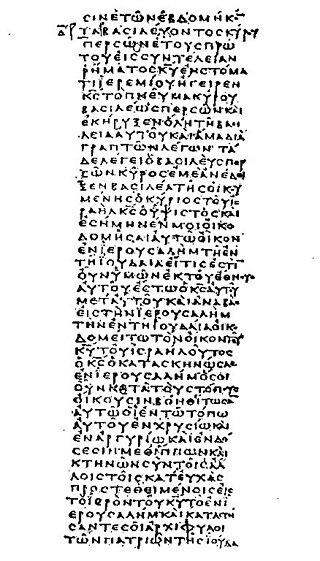

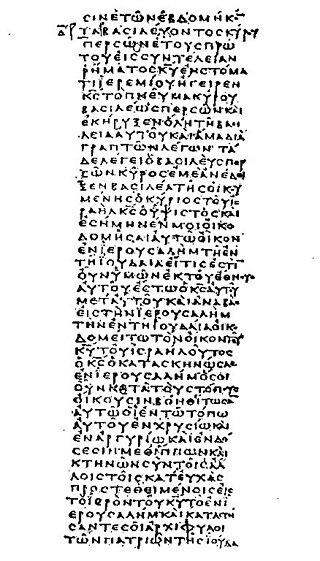

The Septuagint, sometimes referred to as the Greek Old Testament or The Translation of the Seventy, and often abbreviated as LXX, is the earliest extant Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible from the original Hebrew. The full Greek title derives from the story recorded in the Letter of Aristeas to Philocrates that "the laws of the Jews" were translated into the Greek language at the request of Ptolemy II Philadelphus by seventy-two Hebrew translators—six from each of the Twelve Tribes of Israel.

The Torah is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. The Torah is known as the Pentateuch or the Five Books of Moses by Christians. It is also known as the Written Torah in Rabbinical Jewish tradition. If meant for liturgic purposes, it takes the form of a Torah scroll. If in bound book form, it is called Chumash, and is usually printed with the rabbinic commentaries and the Jews call Torah the daughter of God

The Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, also known in Hebrew as Miqra, is the canonical collection of Hebrew scriptures, comprising the Torah, the Nevi'im, and the Ketuvim. Different branches of Judaism and Samaritanism have maintained different versions of the canon, including the 3rd-century BCE Septuagint text used in Second Temple Judaism, the Syriac Peshitta, the Samaritan Pentateuch, the Dead Sea Scrolls, and most recently the 10th-century medieval Masoretic Text compiled by the Masoretes, currently used in Rabbinic Judaism. The terms "Hebrew Bible" or "Hebrew Canon" are frequently confused with the Masoretic Text; however, this is a medieval version and one of several texts considered authoritative by different types of Judaism throughout history. The current edition of the Masoretic Text is mostly in Biblical Hebrew, with a few passages in Biblical Aramaic.

The Masoretic Text is the authoritative Hebrew and Aramaic text of the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible (Tanakh) in Rabbinic Judaism. The Masoretic Text defines the Jewish canon and its precise letter-text, with its vocalization and accentuation known as the mas'sora. Referring to the Masoretic Text, masorah specifically means the diacritic markings of the text of the Jewish scriptures and the concise marginal notes in manuscripts of the Tanakh which note textual details, usually about the precise spelling of words. It was primarily copied, edited, and distributed by a group of Jews known as the Masoretes between the 7th and 10th centuries of the Common Era (CE). The oldest known complete copy, the Leningrad Codex, dates from the early 11th century CE.

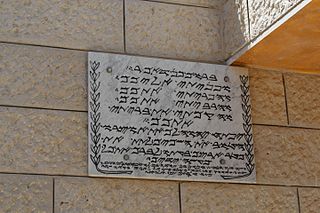

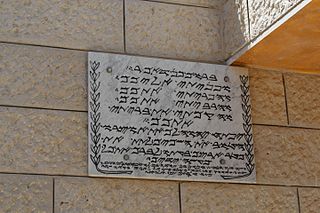

The Samaritan Pentateuch, also called the Samaritan Torah, is the sacred scripture of the Samaritans. Written in the Samaritan script, it dates back to one of the ancient versions of the Torah that existed during the Second Temple period, and constitutes the entire biblical canon in Samaritanism.

The genealogies of Genesis provide the framework around which the Book of Genesis is structured. Beginning with Adam, genealogical material in Genesis 4, 5, 10, 11, 22, 25, 29–30, 35–36, and 46 moves the narrative forward from the creation to the beginnings of the Israelites' existence as a people.

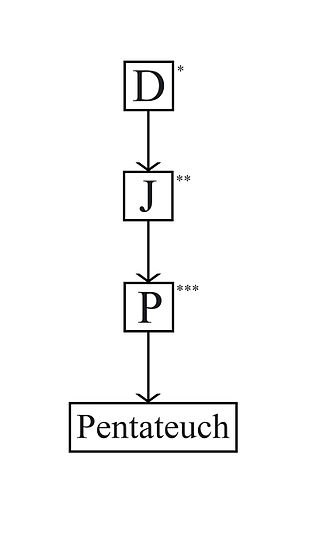

The Priestly source is perhaps the most widely recognized of the sources underlying the Torah, both stylistically and theologically distinct from other material in it. It is considered by most scholars as the latest of all sources, and “meant to be a kind of redactional layer to hold the entirety of the Pentateuch together,” It includes a set of claims that are contradicted by non-Priestly passages and therefore uniquely characteristic: no sacrifice before the institution is ordained by Yahweh (God) at Sinai, the exalted status of Aaron and the priesthood, and the use of the divine title El Shaddai before God reveals his name to Moses, to name a few.

Anno Mundi, abbreviated as AM or A.M., or Year After Creation, is a calendar era based on the biblical accounts of the creation of the world and subsequent history. Two such calendar eras have seen notable use historically:

Biblical Hebrew orthography refers to the various systems which have been used to write the Biblical Hebrew language. Biblical Hebrew has been written in a number of different writing systems over time, and in those systems its spelling and punctuation have also undergone changes.

Biblical literalist chronology is the attempt to correlate the historical dates used in the Bible with the chronology of actual events, typically starting with creation in Genesis 1:1. Some of the better-known calculations include Archbishop James Ussher, who placed it in 4004 BC, Isaac Newton in 4000 BC, Martin Luther in 3961 BC, the traditional Hebrew calendar date of 3760 BC, and lastly the dates based on the Septuagint, of roughly 4650 BC. The dates between the Septuagint & Masoretic are conflicting by 650 years between the genealogy of Arphaxad to Nahor in Genesis 11:12-24. The Masoretic text, which lacks the 650 years of the Septuagint, is the text used by most modern Bibles. There is no consensus of which is right, however, without the additional 650 years in the Septuagint, according to Egyptologists the great Pyramids of Giza would pre-date the Flood and provide no time for Tower of Babel event.

Ancient Hebrew writings are texts written in Biblical Hebrew using the Paleo-Hebrew alphabet before the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE.

Jeremiah 26 is the twenty-sixth chapter of the Book of Jeremiah in the Hebrew Bible or the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. It is numbered as Jeremiah 33 in the Septuagint. This book contains prophecies attributed to the prophet Jeremiah, and is one of the Books of the Prophets. This chapter contains an exhortation to repentance, causing Jeremiah to be apprehended and arraigned ; he gives his apology, resulting the princes to clear him by the example of Micah and of Urijah, and by the care of Ahikam.

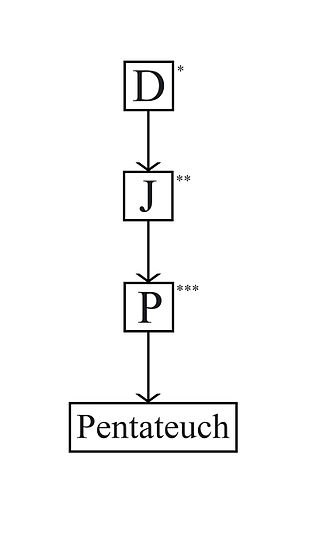

The composition of the Torah was a process that involved multiple authors over an extended period of time. While Jewish tradition holds that all five books were originally written by Moses sometime in the 2nd millennium BCE, leading scholars have rejected Mosaic authorship since the 17th century.

2 Kings 10 is the tenth chapter of the second part of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the Second Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. This chapter records Jehu's massacres of the sons of Ahab, the kinsmen of Ahaziah the king of Judah and the Baal worshippers linked to Jezebel. The narrative is a part of a major section 2 Kings 9:1–15:12 covering the period of Jehu's dynasty.

1 Kings 12 is the twelfth chapter of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the First Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. 1 Kings 12:1 to 16:14 documents the consolidation of the kingdoms of northern Israel and Judah: this chapter focusses on the reigns of Rehoboam and Jeroboam.

1 Kings 14 is the fourteenth chapter of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the First Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. 1 Kings 12:1 to 16:14 documents the consolidation of the kingdoms of northern Israel and Judah: this chapter focusses on the reigns of Jeroboam and Nadab in the northern kingdom and Rehoboam in the southern kingdom.

1 Kings 15 is the fifteenth chapter of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the First Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. 1 Kings 12:1-16:14 documents the consolidation of the kingdoms of northern Israel and Judah. This chapter focusses on the reigns of Abijam and Asa in the southern kingdom, as well as Nadab and Baasha in the northern kingdom.

1 Kings 16 is the sixteenth chapter of the Books of Kings in the Hebrew Bible or the First Book of Kings in the Old Testament of the Christian Bible. The book is a compilation of various annals recording the acts of the kings of Israel and Judah by a Deuteronomic compiler in the seventh century BCE, with a supplement added in the sixth century BCE. 1 Kings 12:1-16:14 documents the consolidation of the kingdoms of northern Israel and Judah. This chapter focusses on the reigns of Baasha, Elah, Zimri, Omri and Ahab in the northern kingdom during the reign of Asa in the southern kingdom.