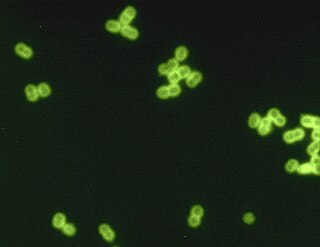

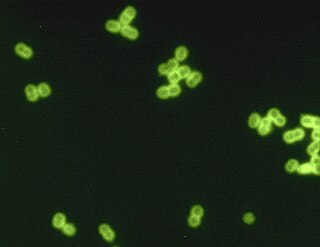

Streptococcus is a genus of gram-positive coccus or spherical bacteria that belongs to the family Streptococcaceae, within the order Lactobacillales, in the phylum Bacillota. Cell division in streptococci occurs along a single axis, so as they grow, they tend to form pairs or chains that may appear bent or twisted. This differs from staphylococci, which divide along multiple axes, thereby generating irregular, grape-like clusters of cells. Most streptococci are oxidase-negative and catalase-negative, and many are facultative anaerobes.

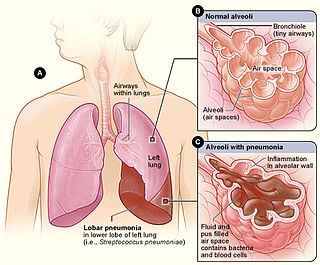

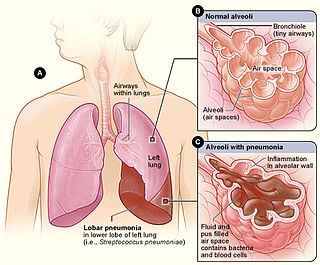

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity of the condition is variable.

Atypical pneumonia, also known as walking pneumonia, is any type of pneumonia not caused by one of the pathogens most commonly associated with the disease. Its clinical presentation contrasts to that of "typical" pneumonia. A variety of microorganisms can cause it. When it develops independently from another disease, it is called primary atypical pneumonia (PAP).

Mycoplasma pneumoniae is a very small bacterium in the class Mollicutes. It is a human pathogen that causes the disease mycoplasma pneumonia, a form of atypical bacterial pneumonia related to cold agglutinin disease. M. pneumoniae is characterized by the absence of a peptidoglycan cell wall and resulting resistance to many antibacterial agents. The persistence of M. pneumoniae infections even after treatment is associated with its ability to mimic host cell surface composition.

Streptococcus pneumoniae, or pneumococcus, is a Gram-positive, spherical bacteria, alpha-hemolytic member of the genus Streptococcus. They are usually found in pairs (diplococci) and do not form spores and are non motile. As a significant human pathogenic bacterium S. pneumoniae was recognized as a major cause of pneumonia in the late 19th century, and is the subject of many humoral immunity studies.

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is a term often used as a synonym for pneumonia but can also be applied to other types of infection including lung abscess and acute bronchitis. Symptoms include shortness of breath, weakness, fever, coughing and fatigue. A routine chest X-ray is not always necessary for people who have symptoms of a lower respiratory tract infection.

Bacterial pneumonia is a type of pneumonia caused by bacterial infection.

Aspiration pneumonia is a type of lung infection that is due to a relatively large amount of material from the stomach or mouth entering the lungs. Signs and symptoms often include fever and cough of relatively rapid onset. Complications may include lung abscess, acute respiratory distress syndrome, empyema, and parapneumonic effusion. Some include chemical induced inflammation of the lungs as a subtype, which occurs from acidic but non-infectious stomach contents entering the lungs.

Bronchopneumonia is a subtype of pneumonia. It is the acute inflammation of the bronchi, accompanied by inflamed patches in the nearby lobules of the lungs.

Chlamydia pneumoniae is a species of Chlamydia, an obligate intracellular bacterium that infects humans and is a major cause of pneumonia. It was known as the Taiwan acute respiratory agent (TWAR) from the names of the two original isolates – Taiwan (TW-183) and an acute respiratory isolate designated AR-39. Briefly, it was known as Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and that name is used as an alternate in some sources. In some cases, to avoid confusion, both names are given.

An opportunistic infection is an infection caused by pathogens that take advantage of an opportunity not normally available. These opportunities can stem from a variety of sources, such as a weakened immune system, an altered microbiome, or breached integumentary barriers. Many of these pathogens do not necessarily cause disease in a healthy host that has a non-compromised immune system, and can, in some cases, act as commensals until the balance of the immune system is disrupted. Opportunistic infections can also be attributed to pathogens which cause mild illness in healthy individuals but lead to more serious illness when given the opportunity to take advantage of an immunocompromised host.

Lung abscess is a type of liquefactive necrosis of the lung tissue and formation of cavities containing necrotic debris or fluid caused by microbial infection.

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia contracted by a person outside of the healthcare system. In contrast, hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) is seen in patients who have recently visited a hospital or who live in long-term care facilities. CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid. This inhibits lung function, causing dyspnea, fever, chest pains and cough.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of lung infection that occurs in people who are on mechanical ventilation breathing machines in hospitals. As such, VAP typically affects critically ill persons that are in an intensive care unit (ICU) and have been on a mechanical ventilator for at least 48 hours. VAP is a major source of increased illness and death. Persons with VAP have increased lengths of ICU hospitalization and have up to a 20–30% death rate. The diagnosis of VAP varies among hospitals and providers but usually requires a new infiltrate on chest x-ray plus two or more other factors. These factors include temperatures of >38 °C or <36 °C, a white blood cell count of >12 × 109/ml, purulent secretions from the airways in the lung, and/or reduction in gas exchange.

Lobar pneumonia is a form of pneumonia characterized by inflammatory exudate within the intra-alveolar space resulting in consolidation that affects a large and continuous area of the lobe of a lung.

Pneumococcal pneumonia is a type of bacterial pneumonia that is caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae (pneumococcus). It is the most common bacterial pneumonia found in adults, the most common type of community-acquired pneumonia, and one of the common types of pneumococcal infection. The estimated number of Americans with pneumococcal pneumonia is 900,000 annually, with almost 400,000 cases hospitalized and fatalities accounting for 5-7% of these cases.

Hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) or nosocomial pneumonia refers to any pneumonia contracted by a patient in a hospital at least 48–72 hours after being admitted. It is thus distinguished from community-acquired pneumonia. It is usually caused by a bacterial infection, rather than a virus.

An acute exacerbation of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or acute exacerbations of chronic bronchitis (AECB), is a sudden worsening of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) symptoms including shortness of breath, quantity and color of phlegm that typically lasts for several days.

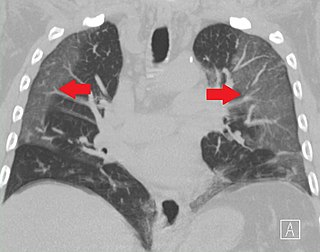

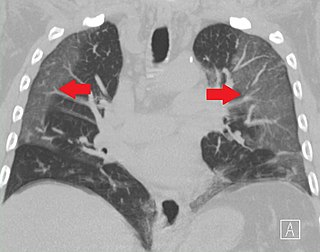

Ground-glass opacity (GGO) is a finding seen on chest x-ray (radiograph) or computed tomography (CT) imaging of the lungs. It is typically defined as an area of hazy opacification (x-ray) or increased attenuation (CT) due to air displacement by fluid, airway collapse, fibrosis, or a neoplastic process. When a substance other than air fills an area of the lung it increases that area's density. On both x-ray and CT, this appears more grey or hazy as opposed to the normally dark-appearing lungs. Although it can sometimes be seen in normal lungs, common pathologic causes include infections, interstitial lung disease, and pulmonary edema.

Necrotizing pneumonia (NP), also known as cavitary pneumonia or cavitatory necrosis, is a rare but severe complication of lung parenchymal infection. In necrotizing pneumonia, there is a substantial liquefaction following death of the lung tissue, which may lead to gangrene formation in the lung. In most cases patients with NP have fever, cough and bad breath, and those with more indolent infections have weight loss. Often patients clinically present with acute respiratory failure. The most common pathogens responsible for NP are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae. Diagnosis is usually done by chest imaging, e.g. chest X-ray, CT scan. Among these CT scan is the most sensitive test which shows loss of lung architecture and multiple small thin walled cavities. Often cultures from bronchoalveolar lavage and blood may be done for identification of the causative organism(s). It is primarily managed by supportive care along with appropriate antibiotics. However, if patient develops severe complications like sepsis or fails to medical therapy, surgical resection is a reasonable option for saving life.