Vaccination is the administration of a vaccine to help the immune system develop immunity from a disease. Vaccines contain a microorganism or virus in a weakened, live or killed state, or proteins or toxins from the organism. In stimulating the body's adaptive immunity, they help prevent sickness from an infectious disease. When a sufficiently large percentage of a population has been vaccinated, herd immunity results. Herd immunity protects those who may be immunocompromised and cannot get a vaccine because even a weakened version would harm them. The effectiveness of vaccination has been widely studied and verified. Vaccination is the most effective method of preventing infectious diseases; widespread immunity due to vaccination is largely responsible for the worldwide eradication of smallpox and the elimination of diseases such as polio and tetanus from much of the world. However, some diseases, such as measles outbreaks in America, have seen rising cases due to relatively low vaccination rates in the 2010s – attributed, in part, to vaccine hesitancy. According to the World Health Organization, vaccination prevents 3.5–5 million deaths per year.

A vaccine is a biological preparation that provides active acquired immunity to a particular infectious or malignant disease. The safety and effectiveness of vaccines has been widely studied and verified. A vaccine typically contains an agent that resembles a disease-causing microorganism and is often made from weakened or killed forms of the microbe, its toxins, or one of its surface proteins. The agent stimulates the body's immune system to recognize the agent as a threat, destroy it, and recognize further and destroy any of the microorganisms associated with that agent that it may encounter in the future.

Herd immunity is a form of indirect protection that applies only to contagious diseases. It occurs when a sufficient percentage of a population has become immune to an infection, whether through previous infections or vaccination, thereby reducing the likelihood of infection for individuals who lack immunity.

Whooping cough, also known as pertussis or the 100-day cough, is a highly contagious, vaccine-preventable bacterial disease. Initial symptoms are usually similar to those of the common cold with a runny nose, fever, and mild cough, but these are followed by two or three months of severe coughing fits. Following a fit of coughing, a high-pitched whoop sound or gasp may occur as the person breathes in. The violent coughing may last for 10 or more weeks, hence the phrase "100-day cough". The cough may be so hard that it causes vomiting, rib fractures, and fatigue. Children less than one year old may have little or no cough and instead have periods where they cannot breathe. The incubation period is usually seven to ten days. Disease may occur in those who have been vaccinated, but symptoms are typically milder.

The DPT vaccine or DTP vaccine is a class of combination vaccines against three infectious diseases in humans: diphtheria, pertussis, and tetanus (lockjaw). The vaccine components include diphtheria and tetanus toxoids, and either killed whole cells of the bacterium that causes pertussis or pertussis antigens. The term toxoid refers to vaccines which use an inactivated toxin produced by the pathogen which they are targeted against to generate an immune response. In this way, the toxoid vaccine generates an immune response which is targeted against the toxin which is produced by the pathogen and causes disease, rather than a vaccine which is targeted against the pathogen itself. The whole cells or antigens will be depicted as either "DTwP" or "DTaP", where the lower-case "w" indicates whole-cell inactivated pertussis and the lower-case "a" stands for "acellular". In comparison to alternative vaccine types, such as live attenuated vaccines, the DTP vaccine does not contain any live pathogen, but rather uses inactivated toxoid to generate an immune response; therefore, there is not a risk of use in populations that are immune compromised since there is not any known risk of causing the disease itself. As a result, the DTP vaccine is considered a safe vaccine to use in anyone and it generates a much more targeted immune response specific for the pathogen of interest.

A vaccination schedule is a series of vaccinations, including the timing of all doses, which may be either recommended or compulsory, depending on the country of residence. A vaccine is an antigenic preparation used to produce active immunity to a disease, in order to prevent or reduce the effects of infection by any natural or "wild" pathogen. Vaccines go through multiple phases of trials to ensure safety and effectiveness.

The schedule for childhood immunizations in the United States is published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The vaccination schedule is broken down by age: birth to six years of age, seven to eighteen, and adults nineteen and older. Childhood immunizations are key in preventing diseases with epidemic potential.

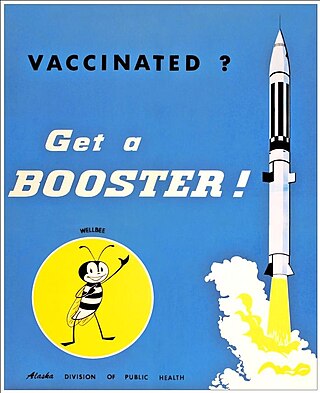

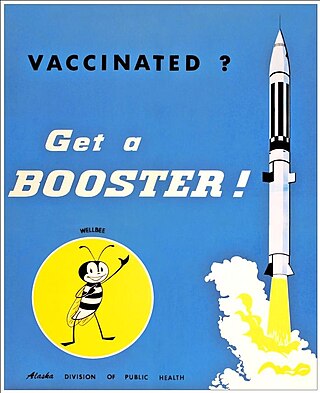

A booster dose is an extra administration of a vaccine after an earlier (primer) dose. After initial immunization, a booster provides a re-exposure to the immunizing antigen. It is intended to increase immunity against that antigen back to protective levels after memory against that antigen has declined through time. For example, tetanus shot boosters are often recommended every 10 years, by which point memory cells specific against tetanus lose their function or undergo apoptosis.

In immunology, passive immunity is the transfer of active humoral immunity of ready-made antibodies. Passive immunity can occur naturally, when maternal antibodies are transferred to the fetus through the placenta, and it can also be induced artificially, when high levels of antibodies specific to a pathogen or toxin are transferred to non-immune persons through blood products that contain antibodies, such as in immunoglobulin therapy or antiserum therapy. Passive immunization is used when there is a high risk of infection and insufficient time for the body to develop its own immune response, or to reduce the symptoms of ongoing or immunosuppressive diseases. Passive immunization can be provided when people cannot synthesize antibodies, and when they have been exposed to a disease that they do not have immunity against.

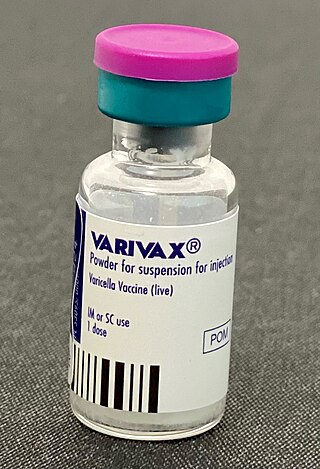

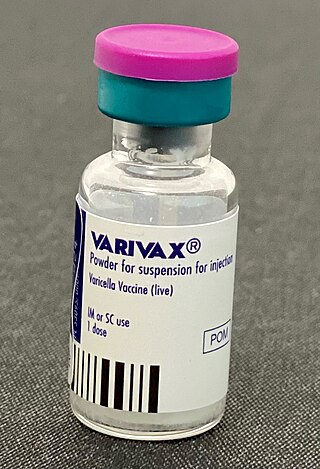

A breakthrough infection is a case of illness in which a vaccinated individual becomes infected with the illness, because the vaccine has failed to provide complete immunity against the pathogen. Breakthrough infections have been identified in individuals immunized against a variety of diseases including mumps, varicella (Chickenpox), influenza, and COVID-19. The characteristics of the breakthrough infection are dependent on the virus itself. Often, infection of the vaccinated individual results in milder symptoms and shorter duration than if the infection were contracted naturally.

Varicella vaccine, also known as chickenpox vaccine, is a vaccine that protects against chickenpox. One dose of vaccine prevents 95% of moderate disease and 100% of severe disease. Two doses of vaccine are more effective than one. If given to those who are not immune within five days of exposure to chickenpox it prevents most cases of disease. Vaccinating a large portion of the population also protects those who are not vaccinated. It is given by injection just under the skin. Another vaccine, known as zoster vaccine, is used to prevent diseases caused by the same virus – the varicella zoster virus.

Hepatitis B vaccine is a vaccine that prevents hepatitis B. The first dose is recommended within 24 hours of birth with either two or three more doses given after that. This includes those with poor immune function such as from HIV/AIDS and those born premature. It is also recommended that health-care workers be vaccinated. In healthy people, routine immunization results in more than 95% of people being protected.

The Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine, also known as Hib vaccine, is a vaccine used to prevent Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) infection. In countries that include it as a routine vaccine, rates of severe Hib infections have decreased more than 90%. It has therefore resulted in a decrease in the rate of meningitis, pneumonia, and epiglottitis.

Diphtheria vaccine is a toxoid vaccine against diphtheria, an illness caused by Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Its use has resulted in a more than 90% decrease in number of cases globally between 1980 and 2000. The first dose is recommended at six weeks of age with two additional doses four weeks apart, after which it is about 95% effective during childhood. Three further doses are recommended during childhood. It is unclear if further doses later in life are needed.

Pertussis vaccine is a vaccine that protects against whooping cough (pertussis). There are two main types: whole-cell vaccines and acellular vaccines. The whole-cell vaccine is about 78% effective while the acellular vaccine is 71–85% effective. The effectiveness of the vaccines appears to decrease by between 2 and 10% per year after vaccination with a more rapid decrease with the acellular vaccines. The vaccine is only available in combination with tetanus and diphtheria vaccines. Pertussis vaccine is estimated to have saved over 500,000 lives in 2002.

Meningococcal vaccine refers to any vaccine used to prevent infection by Neisseria meningitidis. Different versions are effective against some or all of the following types of meningococcus: A, B, C, W-135, and Y. The vaccines are between 85 and 100% effective for at least two years. They result in a decrease in meningitis and sepsis among populations where they are widely used. They are given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

Yellow fever vaccine is a vaccine that protects against yellow fever. Yellow fever is a viral infection that occurs in Africa and South America. Most people begin to develop immunity within ten days of vaccination and 99% are protected within one month, and this appears to be lifelong. The vaccine can be used to control outbreaks of disease. It is given either by injection into a muscle or just under the skin.

Tetanus vaccine, also known as tetanus toxoid (TT), is a toxoid vaccine used to prevent tetanus. During childhood, five doses are recommended, with a sixth given during adolescence.

Ring vaccination is a strategy to inhibit the spread of a disease by vaccinating those who are most likely to be infected.

DTaP-IPV-HepB vaccine is a combination vaccine whose generic name is diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis adsorbed, hepatitis B (recombinant) and inactivated polio vaccine or DTaP-IPV-Hep B. It protects against the infectious diseases diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis, and hepatitis B.