An electric current is a flow of charged particles, such as electrons or ions, moving through an electrical conductor or space. It is defined as the net rate of flow of electric charge through a surface. The moving particles are called charge carriers, which may be one of several types of particles, depending on the conductor. In electric circuits the charge carriers are often electrons moving through a wire. In semiconductors they can be electrons or holes. In an electrolyte the charge carriers are ions, while in plasma, an ionized gas, they are ions and electrons.

Cathode rays or electron beams (e-beam) are streams of electrons observed in discharge tubes. If an evacuated glass tube is equipped with two electrodes and a voltage is applied, glass behind the positive electrode is observed to glow, due to electrons emitted from the cathode. They were first observed in 1859 by German physicist Julius Plücker and Johann Wilhelm Hittorf, and were named in 1876 by Eugen Goldstein Kathodenstrahlen, or cathode rays. In 1897, British physicist J. J. Thomson showed that cathode rays were composed of a previously unknown negatively charged particle, which was later named the electron. Cathode-ray tubes (CRTs) use a focused beam of electrons deflected by electric or magnetic fields to render an image on a screen.

The Geiger–Müller tube or G–M tube is the sensing element of the Geiger counter instrument used for the detection of ionizing radiation. It is named after Hans Geiger, who invented the principle in 1908, and Walther Müller, who collaborated with Geiger in developing the technique further in 1928 to produce a practical tube that could detect a number of different radiation types.

The Biefeld–Brown effect is an electrical phenomenon that produces an ionic wind that transfers its momentum to surrounding neutral particles. It describes a force observed on an asymmetric capacitor when high voltage is applied to the capacitor's electrodes. Once suitably charged up to high DC potentials, a thrust at the negative terminal, pushing it away from the positive terminal, is generated. The effect was named by inventor Thomas Townsend Brown who claimed that he did a series of experiments with professor of astronomy Paul Alfred Biefeld, a former teacher of Brown whom Brown claimed was his mentor and co-experimenter at Denison University in Ohio.

Paschen's law is an equation that gives the breakdown voltage, that is, the voltage necessary to start a discharge or electric arc, between two electrodes in a gas as a function of pressure and gap length. It is named after Friedrich Paschen who discovered it empirically in 1889.

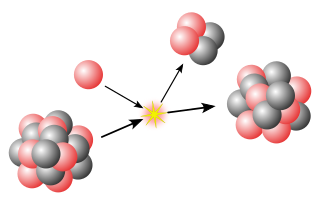

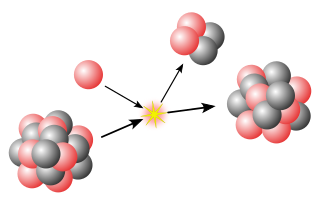

Neutron generators are neutron source devices which contain compact linear particle accelerators and that produce neutrons by fusing isotopes of hydrogen together. The fusion reactions take place in these devices by accelerating either deuterium, tritium, or a mixture of these two isotopes into a metal hydride target which also contains deuterium, tritium or a mixture of these isotopes. Fusion of deuterium atoms results in the formation of a helium-3 ion and a neutron with a kinetic energy of approximately 2.5 MeV. Fusion of a deuterium and a tritium atom results in the formation of a helium-4 ion and a neutron with a kinetic energy of approximately 14.1 MeV. Neutron generators have applications in medicine, security, and materials analysis.

In electronics, electrical breakdown or dielectric breakdown is a process that occurs when an electrically insulating material, subjected to a high enough voltage, suddenly becomes a conductor and current flows through it. All insulating materials undergo breakdown when the electric field caused by an applied voltage exceeds the material's dielectric strength. The voltage at which a given insulating object becomes conductive is called its breakdown voltage and, in addition to its dielectric strength, depends on its size and shape, and the location on the object at which the voltage is applied. Under sufficient voltage, electrical breakdown can occur within solids, liquids, or gases. However, the specific breakdown mechanisms are different for each kind of dielectric medium.

A glow discharge is a plasma formed by the passage of electric current through a gas. It is often created by applying a voltage between two electrodes in a glass tube containing a low-pressure gas. When the voltage exceeds a value called the striking voltage, the gas ionization becomes self-sustaining, and the tube glows with a colored light. The color depends on the gas used.

An electric arc is an electrical breakdown of a gas that produces a prolonged electrical discharge. The current through a normally nonconductive medium such as air produces a plasma, which may produce visible light. An arc discharge is initiated either by thermionic emission or by field emission. After initiation, the arc relies on thermionic emission of electrons from the electrodes supporting the arc. An arc discharge is characterized by a lower voltage than a glow discharge. An archaic term is voltaic arc, as used in the phrase "voltaic arc lamp".

Ion wind, ionic wind, corona wind or electric wind is the airflow of charged particles induced by electrostatic forces linked to corona discharge arising at the tips of some sharp conductors subjected to high voltage relative to ground. Ion wind is an electrohydrodynamic phenomenon. Ion wind generators can also be considered electrohydrodynamic thrusters.

An electron avalanche is a process in which a number of free electrons in a transmission medium are subjected to strong acceleration by an electric field and subsequently collide with other atoms of the medium, thereby ionizing them. This releases additional electrons which accelerate and collide with further atoms, releasing more electrons—a chain reaction. In a gas, this causes the affected region to become an electrically conductive plasma.

In electromagnetism, the Townsend discharge or Townsend avalanche is an ionisation process for gases where free electrons are accelerated by an electric field, collide with gas molecules, and consequently free additional electrons. Those electrons are in turn accelerated and free additional electrons. The result is an avalanche multiplication that permits significantly increased electrical conduction through the gas. The discharge requires a source of free electrons and a significant electric field; without both, the phenomenon does not occur.

A brush discharge is an electrical disruptive discharge similar to a corona discharge that takes place at an electrode with a high voltage applied to it, embedded in a nonconducting fluid, usually air. It is characterized by numerous luminous writhing sparks, plasma streamers composed of ionized air molecules, which repeatedly strike out from the electrode into the air, often with a crackling sound. The streamers spread out in a fan shape, giving it the appearance of a "brush".

Plasma activation is a method of surface modification employing plasma processing, which improves surface adhesion properties of many materials including metals, glass, ceramics, a broad range of polymers and textiles and even natural materials such as wood and seeds. Plasma functionalization also refers to the introduction of functional groups on the surface of exposed materials. It is widely used in industrial processes to prepare surfaces for bonding, gluing, coating and painting. Plasma processing achieves this effect through a combination of reduction of metal oxides, ultra-fine surface cleaning from organic contaminants, modification of the surface topography and deposition of functional chemical groups. Importantly, the plasma activation can be performed at atmospheric pressure using air or typical industrial gases including hydrogen, nitrogen and oxygen. Thus, the surface functionalization is achieved without expensive vacuum equipment or wet chemistry, which positively affects its costs, safety and environmental impact. Fast processing speeds further facilitate numerous industrial applications.

Plasma-enhanced chemical vapor deposition (PECVD) is a chemical vapor deposition process used to deposit thin films from a gas state (vapor) to a solid state on a substrate. Chemical reactions are involved in the process, which occur after creation of a plasma of the reacting gases. The plasma is generally created by radio frequency (RF) frequency or direct current (DC) discharge between two electrodes, the space between which is filled with the reacting gases.

A microplasma is a plasma of small dimensions, ranging from tens to thousands of micrometers. Microplasmas can be generated at a variety of temperatures and pressures, existing as either thermal or non-thermal plasmas. Non-thermal microplasmas that can maintain their state at standard temperatures and pressures are readily available and accessible to scientists as they can be easily sustained and manipulated under standard conditions. Therefore, they can be employed for commercial, industrial, and medical applications, giving rise to the evolving field of microplasmas.

Plasma is one of four fundamental states of matter characterized by the presence of a significant portion of charged particles in any combination of ions or electrons. It is the most abundant form of ordinary matter in the universe, mostly in stars, but also dominating the rarefied intracluster medium and intergalactic medium. Plasma can be artificially generated, for example, by heating a neutral gas or subjecting it to a strong electromagnetic field.

In electromagnetism, a streamer discharge, also known as filamentary discharge, is a type of transient electric discharge which forms at the surface of a conductive electrode carrying a high voltage in an insulating medium such as air. Streamers are luminous writhing branching sparks, plasma channels composed of ionized air molecules, which repeatedly strike out from the electrode into the air.

Piezoelectric direct discharge (PDD) plasma is a type of cold non-equilibrium plasma, generated by a direct gas discharge of a high voltage piezoelectric transformer. It can be ignited in air or other gases in a wide range of pressures, including atmospheric. Due to the compactness and the efficiency of the piezoelectric transformer, this method of plasma generation is particularly compact, efficient and cheap. It enables a wide spectrum of industrial, medical and consumer applications.