A coalition government, or coalition cabinet, is a government where political parties enter a power-sharing arrangement of the executive. Coalition governments usually occur when no single party has achieved an absolute majority after an election. A party not having majority is common under proportional representation, but not in nations with majoritarian electoral systems.

Politics of Malaysia takes place in the framework of a federal representative democratic constitutional monarchy, in which the Yang di-Pertuan Agong is head of state and the Prime Minister of Malaysia is the head of government. Executive power is exercised by the federal government and the 13 state governments. Legislative power is vested in the federal parliament and the 13 state assemblies. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature, though the executive maintains a certain level of influence in the appointment of judges to the courts.

Politics in Austria reflects the dynamics of competition among multiple political parties, which led to the formation of a Conservative-Green coalition government for the first time in January 2020, following the snap elections of 29 September 2019, and the election of a former Green Party leader to the presidency in 2016.

The National Front is a political coalition of Malaysia that was founded in 1973 as a coalition of centre-right and right-wing political parties to succeed the Alliance Party. It is the third largest political coalition with 30 seats in the Dewan Rakyat after Pakatan Harapan (PH) with 82 seats and Perikatan Nasional (PN) with 74 seats.

The Malaysian Chinese Association is a uni-racial political party in Malaysia that seeks to represent the Malaysian Chinese ethnicity; it was one of the three original major component parties of the coalition party in Malaysia called the Alliance Party, which later became a broader coalition called Barisan Nasional in Malay, or National Front in English.

The People's Justice Party ; often known simply as KEADILAN or PKR, is a reformist political party in Malaysia formed on 3 August 2003 through a merger of the party's predecessor, the National Justice Party, with the socialist Malaysian People's Party. The party's predecessor was founded by Wan Azizah Wan Ismail during the height of the Reformasi movement on 4 April 1999 after the arrest of her husband, former Deputy Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim. The party is one of main partners of the Pakatan Harapan (PH) coalition.

A hung parliament is a term used in legislatures primarily under the Westminster system to describe a situation in which no single political party or pre-existing coalition has an absolute majority of legislators in a parliament or other legislature. This situation is also known as a balanced parliament, or as a legislature under no overall control (NOC), and can result in a minority government.

The Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia is a liberal political party in Malaysia. Formed in 1968, Gerakan gained prominence in the 1969 general election when it defeated the ruling Alliance Party in Penang and won the majority of seats in Penang's state legislature. In 1972, Gerakan joined the Alliance Party, which later became Barisan Nasional coalition Party (BN), the ruling coalition of Malaysia until 2018. The party left the BN in 2018 and is currently part of the Perikatan Nasional coalition Party (PN).

An electoral wipeout occurs when a major party receives far fewer votes or seats in a legislature than their position justifies. It is the opposite of a landslide victory; the two frequently go hand in hand.

General elections were held in Malaysia on 20 and 21 October 1990. Voting took place in all 180 parliamentary constituencies of Malaysia, each electing one Member of Parliament to the Dewan Rakyat, the dominant house of Parliament. State elections also took place in 351 state constituencies in 11 states of Malaysia on the same day.

The Alliance Party was a political coalition in Malaysia. The Alliance Party, whose membership comprised United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Malaysian Chinese Association (MCA) and Malaysian Indian Congress (MIC), was formally registered as a political organisation on 30 October 1957. It was the ruling coalition of Malaya from 1957 to 1963, and Malaysia from 1963 to 1973. The coalition became the Barisan Nasional in 1973.

The Social Democratic Party of Austria is a social-democratic political party in Austria. Founded in 1889 as the Social Democratic Workers' Party of Austria and later known as the Socialist Party of Austria from 1945 until 1991, the party is the oldest extant political party in Austria. Along with the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP), it is one of the country's two traditional major parties. It is positioned on the centre-left on the political spectrum.

A landslide victory is an election result in which the victorious candidate or party wins by an overwhelming margin. The term became popular in the 1800s to describe a victory in which the opposition is "buried", similar to the way in which a geological landslide buries whatever is in its path. A landslide victory is the opposite of an electoral wipeout; a party which wins in a landslide typically inflicts a wipeout on its opposition.

The Alliance of Hope is a Malaysian political coalition consisting of centre-left political parties which was formed in 2015 to succeed the Pakatan Rakyat coalition. It has been part of a "Unity Government" since November 2022 together with other political coalitions and parties as a result of the 2022 Malaysian general election, and previously for 22 months after it had won the 2018 Malaysian general election until February 2020 when it lost power as a result of the 2020 Malaysian political crisis at the federal level. The coalition deposed the Barisan Nasional coalition government during the 2018 election, ending its 60-year-long reign since independence.

The National Alliance is a political coalition composed of the Malaysian United Indigenous Party, Malaysian Islamic Party, Malaysian People's Movement Party, Sabah Progressive Party and Malaysian Indian People's Party This coalition was preceded by the Malaysian Party Alliance Association, also known as the Persatuan Perikatan Parti Malaysia (PPPM). It is the second largest political coalition in Dewan Rakyat with 74 seats after Pakatan Harapan (PH) with 81 seats; dubbed as the "Green Wave".

Dominic Lau Hoe Chai is a Malaysian politician who has served as Senator since November 2021 and 6th President of the Parti Gerakan Rakyat Malaysia (GERAKAN), a component party of the Perikatan Nasional (PN) coalition, since November 2018. He succeeded Mah Siew Keong as party president in November 2018. He was appointed as a Senator to the Dewan Negara in November 2021.

The 2022 Pahang state election, formally the 15th Pahang state election, took place on 19 November 2022. This election was to elect 42 members of the 15th Pahang State Legislative Assembly. The previous assembly was dissolved on 14 October 2022. The election for the Tioman was delayed to 7 December following the death of the Perikatan candidate.

The 2022 Perak state election, formally the 15th Perak state election, took place on 19 November 2022. This election was to elect 59 members of the 15th Perak State Legislative Assembly. The previous assembly was dissolved on 17 October 2022.

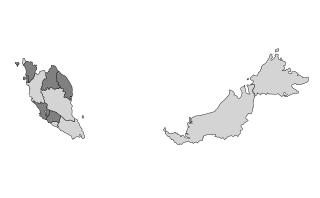

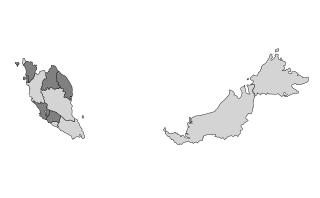

State elections in 2023 were held in Selangor, Kelantan, Terengganu, Negeri Sembilan, Kedah and Penang on 12 August 2023, following the dissolution of their state assemblies between 22 June and 1 July 2023.

Green Wave, also known as Green Tsunami, better known as Malay Wave, also known as Malay Tsunami, otherwise known as The People's Wave, alternatively known as Perikatan Nasional Wave / National Pact Wave, shortened as PN Wave, is a political phenomenon that has taken place in Malaysia since the 2022 Malaysian general election. This political phenomenon involves Malaysian Islamic Party (PAS) and its ultraconservative voters, who mainly originate from the northeastern and northwestern parts of Peninsular Malaysia. Ideologically, the phenomenon mostly concerns a far-right, authoritarian and ultranationalist movement that espouses increased Malay–Muslim hegemony in Malaysian politics as well as further intimidation and marginalisation of Malaysia's minority groups and religions.