The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Northwestern and Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and early medieval Germanic languages and are thus equated at least approximately with Germanic-speaking peoples, although different academic disciplines have their own definitions of what makes someone or something "Germanic". The Romans named the area belonging to North-Central Europe in which Germanic peoples lived Germania, stretching east to west between the Vistula and Rhine rivers and north to south from southern Scandinavia to the upper Danube. In discussions of the Roman period, the Germanic peoples are sometimes referred to as Germani or ancient Germans, although many scholars consider the second term problematic since it suggests identity with present-day Germans. The very concept of "Germanic peoples" has become the subject of controversy among contemporary scholars. Some scholars call for its total abandonment as a modern construct since lumping "Germanic peoples" together implies a common group identity for which there is little evidence. Other scholars have defended the term's continued use and argue that a common Germanic language allows one to speak of "Germanic peoples", regardless of whether these ancient and medieval peoples saw themselves as having a common identity. While several historians and archaeologists continue to use the term "Germanic peoples" to refer to historical people groups from the 1st to 4th centuries CE, the term is no longer used by most historians and archaeologists for the period around the Fall of the Roman Empire and the Early Middle Ages.

The Battle of the Teutoburg Forest, described as the Varian Disaster by Roman historians, was a major battle between Germanic tribes and the Roman Empire that took place somewhere near modern Kalkriese from September 8–11, 9 AD, when an alliance of Germanic peoples ambushed three Roman legions led by Publius Quinctilius Varus and their auxiliaries. The alliance was led by Arminius, a Germanic officer of Varus's auxilia. Arminius had acquired Roman citizenship and had received a Roman military education, which enabled him to deceive the Roman commander methodically and anticipate the Roman army's tactical responses.

The Rugii, Rogi or Rugians, were a Roman-era Germanic people. They were first clearly recorded by Tacitus, in his Germania who called them the Rugii, and located them near the south shore of the Baltic Sea. Some centuries later, they were considered one of the "Gothic" or "Scythian" peoples who were located in the Middle Danube region. Like several other Gothic peoples there, they possibly arrived in the area as allies of Attila until his death in 453. They settled in what is now Lower Austria after the defeat of the Huns at Nedao in 454.

The Migration Period, also known as the Barbarian Invasions, was a period in European history marked by large-scale migrations that saw the fall of the Western Roman Empire and subsequent settlement of its former territories by various tribes, and the establishment of the post-Roman kingdoms.

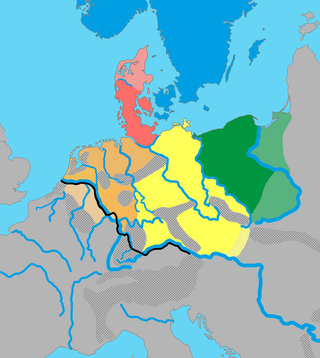

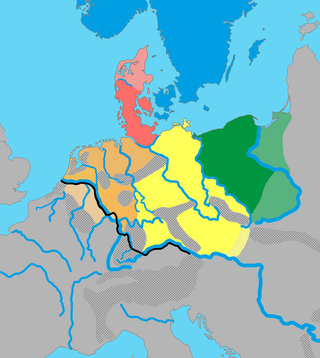

Germania, also called Magna Germania, Germania Libera, or Germanic Barbaricum to distinguish it from the Roman province of the same name, was a historical region in north-central Europe during the Roman era, which was associated by Roman authors with the Germanic people. The region stretched roughly from the Middle and Lower Rhine in the west to the Vistula in the east. It also extended at some point as far south as the Upper and Middle Danube and Pannonia, and to the known parts of southern Scandinavia in the north. Archaeologically, these people correspond roughly to the Roman Iron Age of those regions. While dominated by Germanic people, Magna Germania was also inhabited by a few other Indo-European people.

The Belgae were a large confederation of tribes living in northern Gaul, between the English Channel, the west bank of the Rhine, and the northern bank of the river Seine, from at least the third century BC. They were discussed in depth by Julius Caesar in his account of his wars in Gaul. Some peoples in southern Britain were also called Belgae and had apparently moved from the continent. T. F. O'Rahilly believed that some had moved further west and he equated them with the Fir Bolg in Ireland. The Roman province of Gallia Belgica was named after the continental Belgae. The term continued to be used in the region until the present day and is reflected in the name of the modern country of Belgium.

The Istvaeones were a Germanic group of tribes living near the banks of the Rhine during the Roman Empire which reportedly shared a common culture and origin. The Istaevones were contrasted to neighbouring groups, the Ingaevones on the North Sea coast, and the Herminones, living inland of these groups.

The Tungri were a tribe, or group of tribes, who lived in the Belgic part of Gaul, during the times of the Roman Empire. Within the Roman Empire, their territory was called the Civitas Tungrorum. They were described by Tacitus as being the same people who were first called "Germani" (Germanic), meaning that all other tribes who were later referred to this way, including those in Germania east of the river Rhine, were named after them. More specifically, Tacitus was thereby equating the Tungri with the "Germani Cisrhenani" described generations earlier by Julius Caesar. Their name is the source of several place names in Belgium, Germany and the Netherlands, including Tongeren, Tongerlo Abbey, and Tongelre.

The Eburones were a Gaulish-Germanic tribe dwelling in the northeast of Gaul, who lived north of the Ardennes in the region near that is now the southern Netherlands, eastern Belgium and the German Rhineland, in the period immediately preceding the Roman conquest of the region. Though living in Gaul, they were also described as being both Belgae and Germani.

Germanic paganism or Germanic religion refers to the traditional, culturally significant religion of the Germanic peoples. With a chronological range of at least one thousand years in an area covering Scandinavia, the British Isles, modern Germany, and at times other parts of Europe, the beliefs and practices of Germanic paganism varied. Scholars typically assume some degree of continuity between Roman-era beliefs and those found in Norse paganism, as well as between Germanic religion and reconstructed Indo-European religion and post-conversion folklore, though the precise degree and details of this continuity are subjects of debate. Germanic religion was influenced by neighboring cultures, including that of the Celts, the Romans, and, later, by the Christian religion. Very few sources exist that were written by pagan adherents themselves; instead, most were written by outsiders and can thus present problems for reconstructing authentic Germanic beliefs and practices.

The Condrusi were an ancient Belgic-Germanic tribe dwelling in what is now eastern Belgium during the Gallic Wars and the Roman period. Their ethnic identity remains uncertain. Caesar described them as part of the Germani Cisrhenani, but their tribal name is probably of Celtic origin. Like other Germani Cisrhenani tribes, it is possible that their old Germanic endonym came to be abandoned after a tribal reorganization, that they received their names from their Celtic neighbours, or else that they were fully or partially assimilated into Celtic culture at the time of the Roman invasion of the region in 57 BC.

The Texandri were a Germanic people living between the Scheldt and Rhine rivers in the 1st century AD. They are associated with a region mentioned in the late 4th century as Texandria, a name which survived into the 8th–12th centuries.

For around 450 years, from around 55 BC to around 410 AD, the southern part of the Netherlands was integrated into the Roman Empire. During this time the Romans in the Netherlands had an enormous influence on the lives and culture of the people who lived in the Netherlands at the time and (indirectly) on the generations that followed.

The Sunuci was the name of a tribal grouping with a particular territory within the Roman province of Germania Inferior, which later became Germania Secunda. Within this province, they were in the Civitas Agrippinenses, with its capital at Cologne. They are thought to have been a Germanic tribe, speaking a Germanic language, although they may also have had a mixed ancestry. They lived between the Meuse and Rur rivers in Roman imperial times. In modern terms this was probably in the part of Germany near Aachen, Jülich, Eschweiler and Düren, and the neighbouring areas in the southern Netherlands, around Valkenburg, and eastern Belgium, in part of the old Duchy of Limburg. There is a town just over the Belgian border from Aachen called Sinnich, in Voeren, which may owe its name to them. In other words, they lived just north of the modern northern limits of Romance languages derived from Latin.

The Baetasii were a Germanic tribal grouping within the Roman province of Germania Inferior, which later became Germania Secunda. Their exact location is still unknown, although two proposals are, first, that it might be the source of the name of the Belgian village of Geetbets, and second, that it might be further east, nearer to the Sunuci with whom they interacted in the Batavian revolt, and to the Cugerni who lived at Xanten. The area of Gennep, Goch and Geldern has been proposed for example.

The Cugerni were a Germanic tribal grouping with a particular territory within the Roman province of Germania Inferior, which later became Germania Secunda. More precisely they lived near modern Xanten, and the old Castra Vetera, on the Rhine. This part of Germania Secunda was called the Civitas or Colonia Traiana, and it was also inhabited by the Betasii.

The Germani cisrhenani, or "Left bank Germani", were a group of Germanic peoples who lived west of the Lower Rhine at the time of the Gallic Wars in the mid-1st century BC.

The Civitas Tungrorum was a large Roman administrative district dominating what is now eastern Belgium and the southern Netherlands. In the early days of the Roman Empire it was in the province of Gallia Belgica, but it later joined the neighbouring lower Rhine River border districts, within the province of Germania Inferior. Its capital was Aduatuca Tungrorum, now Tongeren.

Early Germanic culture was the culture of the early Germanic peoples. Largely derived from a synthesis of Proto-Indo-European and indigenous Northern European elements, the Germanic culture started to exist in the Jastorf culture that developed out of the Nordic Bronze Age. It came under significant external influence during the Migration Period, particularly from ancient Rome.

By military organization of the Germanic peoples is meant the set of forces that made up the armies of the Germanic peoples, including the organization of their units, their internal hierarchy of command, tactics, armament and strategy, from the Cimbrian Wars to the Marcomannic Wars. After this period a whole series of confederations of peoples were generated, each with its own internal military organization, which will be analyzed individually and separately.