Spot welding

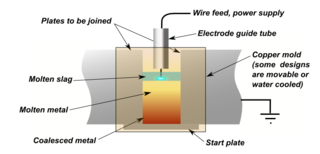

Spot welding is a resistance welding method used to join two or more overlapping metal sheets, studs, projections, electrical wiring hangers, some heat exchanger fins, and some tubing. Usually power sources and welding equipment are sized to the specific thickness and material being welded together. The thickness is limited by the output of the welding power source and thus the equipment range due to the current required for each application. Care is taken to eliminate contaminants between the faying surfaces. Usually, two copper electrodes are simultaneously used to clamp the metal sheets together and to pass current through the sheets. When the current is passed through the electrodes to the sheets, heat is generated due to the higher electrical resistance where the surfaces contact each other. As the electrical resistance of the material causes a heat buildup in the work pieces between the copper electrodes, the rising temperature causes a rising resistance, and results in a molten pool contained most of the time between the electrodes. As the heat dissipates throughout the workpiece in less than a second (resistance welding time is generally programmed as a quantity of AC cycles or milliseconds) the molten or plastic state grows to meet the welding tips. When the current is stopped the copper tips cool the spot weld, causing the metal to solidify under pressure. The water cooled copper electrodes remove the surface heat quickly, accelerating the solidification of the metal, since copper is an excellent conductor. Resistance spot welding typically employs electrical power in the form of direct current, alternating current, medium frequency half-wave direct current, or high-frequency half wave direct current.

If excessive heat is applied or applied too quickly, or if the force between the base materials is too low, or the coating is too thick or too conductive, then the molten area may extend to the exterior of the work pieces, escaping the containment force of the electrodes (often up to 30,000 psi). This burst of molten metal is called expulsion, and when this occurs the metal will be thinner and have less strength than a weld with no expulsion. The common method of checking a weld's quality is a peel test. An alternative test is the restrained tensile test, which is much more difficult to perform, and requires calibrated equipment. Because both tests are destructive in nature (resulting in the loss of salable material), non-destructive methods such as ultrasound evaluation are in various states of early adoption by many OEMs.

The advantages of the method include efficient energy use, limited workpiece deformation, high production rates, easy automation, and no required filler materials. When high strength in shear is needed, spot welding is used in preference to more costly mechanical fastening, such as riveting. While the shear strength of each weld is high, the fact that the weld spots do not form a continuous seam means that the overall strength is often significantly lower than with other welding methods, limiting the usefulness of the process. It is used extensively in the automotive industry – cars can have several thousand spot welds. A specialized process, called shot welding, can be used to spot weld stainless steel.

There are three basic types of resistance welding bonds: solid state, fusion, and reflow braze. In a solid state bond, also called a thermo-compression bond, dissimilar materials with dissimilar grain structure, e.g. molybdenum to tungsten, are joined using a very short heating time, high weld energy, and high force. There is little melting and minimum grain growth, but a definite bond and grain interface. Thus the materials actually bond while still in the solid state. The bonded materials typically exhibit excellent shear and tensile strength, but poor peel strength. In a fusion bond, either similar or dissimilar materials with similar grain structures are heated to the melting point (liquid state) of both. The subsequent cooling and combination of the materials forms a “nugget” alloy of the two materials with larger grain growth. Typically, high weld energies at either short or long weld times, depending on physical characteristics, are used to produce fusion bonds. The bonded materials usually exhibit excellent tensile, peel and shear strengths. In a reflow braze bond, a resistance heating of a low temperature brazing material, such as gold or solder, is used to join either dissimilar materials or widely varied thick/thin material combinations. The brazing material must “wet” to each part and possess a lower melting point than the two workpieces. The resultant bond has definite interfaces with minimum grain growth. Typically the process requires a longer (2 to 100 ms) heating time at low weld energy. The resultant bond exhibits excellent tensile strength, but poor peel and shear strength.