A tampon is a menstrual product designed to absorb blood and vaginal secretions by insertion into the vagina during menstruation. Unlike a pad, it is placed internally, inside of the vaginal canal. Once inserted correctly, a tampon is held in place by the vagina and expands as it soaks up menstrual blood. However, in addition to menstrual blood, the tampon also absorbs the vagina's natural lubrication and bacteria, which can change the normal pH, increasing the risk of infections from the bacterium Staphylococcus aureus, which can lead to toxic shock syndrome (TSS). TSS is a rare but life-threatening infection that requires immediate medical attention.

Vaginitis, also known as vulvovaginitis, is inflammation of the vagina and vulva. Symptoms may include itching, burning, pain, discharge, and a bad smell. Certain types of vaginitis may result in complications during pregnancy.

A menstrual cup is a menstrual hygiene device which is inserted into the vagina during menstruation. Its purpose is to collect menstrual fluid. Menstrual cups are made of elastomers. A properly-fitting menstrual cup seals against the vaginal walls, so tilting and inverting the body will not cause it to leak. It is impermeable and collects menstrual fluid, unlike tampons and menstrual pads, which absorb it.

A menstrual pad, or simply a pad, is an absorbent item worn in the underwear when menstruating, bleeding after giving birth, recovering from gynecologic surgery, experiencing a miscarriage or abortion, or in any other situation where it is necessary to absorb a flow of blood from the vagina. A menstrual pad is a type of menstrual hygiene product that is worn externally, unlike tampons and menstrual cups, which are worn inside the vagina. Pads are generally changed by being stripped off the pants and panties, taking out the old pad, sticking the new one on the inside of the panties and pulling them back on. Pads are recommended to be changed every 3–4 hours to avoid certain bacteria that can fester in blood; this time also may differ depending on the kind worn, flow, and the time it is worn.

A pantyliner is an absorbent piece of material used for feminine hygiene. It is worn in the gusset of a woman's panties. Some uses include: absorbency for daily vaginal discharge, light menstrual flow, tampon and menstrual cup backup, spotting, post-intercourse discharge, and urinary incontinence. Panty liners can also help with girls who are having discharges and about to start their cycle. Pantyliners are related to sanitary napkins in their basic construction—but are usually much thinner and often narrower than pads. As a result, they absorb much less liquid than pads—making them suitable for light discharge and everyday cleanliness. They are generally unsuitable for menstruation with medium to heavy flow, which requires them to be changed more often.

Kotex is an American brand of menstrual hygiene products, which includes the Kotex maxi, thin and ultra-thin pads, the Security tampons, and the Lightdays pantiliners. Most recently, the company has added U by Kotex to its menstrual hygiene product line. Kotex is owned and managed by Kimberly-Clark, a consumer products corporation active in more than 80 countries.

Vulvitis is inflammation of the vulva, the external female mammalian genitalia that include the labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and introitus. It may co-occur as vulvovaginitis with vaginitis, inflammation of the vagina, and may have infectious or non-infectious causes. The warm and moist conditions of the vulva make it easily affected. Vulvitis is prone to occur in any female especially those who have certain sensitivities, infections, allergies, or diseases that make them likely to have vulvitis. Postmenopausal women and prepubescent girls are more prone to be affected by it, as compared to women in their menstruation period. It is so because they have low estrogen levels which makes their vulvar tissue thin and dry. Women having diabetes are also prone to be affected by vulvitis due to the high sugar content in their cells, increasing their vulnerability. Vulvitis is not a disease, it is just an inflammation caused by an infection, allergy or injury. Vulvitis may also be symptom of any sexually transmitted infection or a fungal infection.

Always is an American brand of menstrual hygiene products, including maxi pads, ultra thin pads, pantyliners, disposable underwear for night-time wear, and vaginal wipes. A sister company of Procter & Gamble, it was first invented and introduced in the United States in 1983 by Tom Osborn, a mid-level employee at Procter & Gamble, then nationally in May 1984. By the end of 1984, Always had also been introduced internationally in the United Kingdom, Canada, France, Germany, Arab world, Pakistan and Africa. Despite the Always' pads runaway international success, Procter & Gamble almost fired Tom Osborn twice in the early 1980s as he was developing this product.

Vaginal discharge is a mixture of liquid, cells, and bacteria that lubricate and protect the vagina. This mixture is constantly produced by the cells of the vagina and cervix, and it exits the body through the vaginal opening. The composition, amount, and quality of discharge varies between individuals and can vary throughout the menstrual cycle and throughout the stages of sexual and reproductive development. Normal vaginal discharge may have a thin, watery consistency or a thick, sticky consistency, and it may be clear or white in color. Normal vaginal discharge may be large in volume but typically does not have a strong odor, nor is it typically associated with itching or pain. While most discharge is considered physiologic or represents normal functioning of the body, some changes in discharge can reflect infection or other pathological processes. Infections that may cause changes in vaginal discharge include vaginal yeast infections, bacterial vaginosis, and sexually transmitted infections. The characteristics of abnormal vaginal discharge vary depending on the cause, but common features include a change in color, a foul odor, and associated symptoms such as itching, burning, pelvic pain, or pain during sexual intercourse.

Cloth menstrual pads are cloth pads worn in the underwear to collect menstrual fluid. They are a type of reusable menstrual hygiene product, and are an alternative to sanitary napkins or to menstrual cups. Because they can be reused, they are generally less expensive than disposable pads over time, and reduce the amount of waste produced.

There are many cultural aspects surrounding how societies view menstruation. Different cultures view menstruation in different ways. The basis of many conduct norms and communication about menstruation in western industrial societies is the belief that menstruation should remain hidden. By contrast, in some hunter-gatherer societies, menstrual observances are viewed in a positive light, without any connotation of uncleanness.

A vaginal disease is a pathological condition that affects part or all of the vagina.

A douche is a device used to introduce a stream of water into the body for medical or hygienic reasons, or the stream of water itself. Douche usually refers to vaginal irrigation, the rinsing of the vagina, but it can also refer to the rinsing of any body cavity. A douche bag is a piece of equipment for douching—a bag for holding the fluid used in douching. To avoid transferring intestinal bacteria into the vagina, the same bag must not be used for an enema and a vaginal douche.

Lil-lets is a brand providing feminine hygiene products that operates principally in the UK, Ireland and South Africa. Since 2000, the company has restructured through two management buyouts (MBO) to become a business crossing all sectors of the feminine hygiene market, including tampons, sanitary napkins, pantyliners and intimate care. They also do programmes for schools that teach young girls the changes that occur when they begin to menstruate.

Arunachalam Muruganantham also known as Padman is a social entrepreneur from Coimbatore in Tamil Nadu, India. He is the inventor of a low-cost sanitary pad-making machine and is credited for innovating grassroots mechanisms for generating awareness about traditional unhygienic practices around menstruation in rural India. His mini-machines, which can manufacture sanitary pads for less than a third of the cost of commercial pads, have been installed in 23 of the 29 states of India in rural areas. He is currently planning to expand the production of these machines to 106 nations. The movie Period. End of Sentence. won the Academy Award for Best Documentary for the year 2018. The 2018 Hindi film Pad Man was made on his invention, where he was portrayed by Akshay Kumar.

Judith Esser-Mittag, commonly known as Judith Esser, was a German gynecologist. Her extensive studies of the female anatomy helped her to create an environmentally friendly tampon with no applicator.

Tampon tax is a popular term used to call attention to tampons, and other feminine hygiene products, being subject to value-added tax (VAT) or sales tax, unlike the tax exemption status granted to other products considered basic necessities. Proponents of tax exemption argue that tampons, sanitary napkins, menstrual cups and comparable products constitute basic, unavoidable necessities for women, and any additional taxes constitute a pink tax.

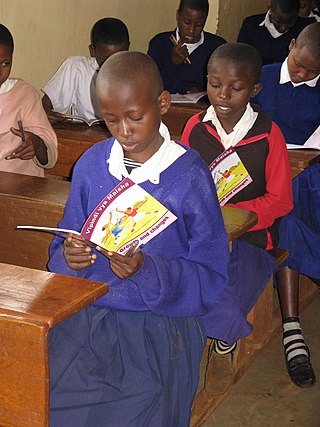

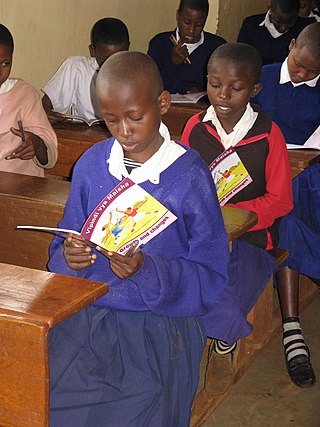

Menstrual hygiene management (MHM) or menstrual health and hygiene (MHH) refers to access to menstrual hygiene products to absorb or collect the flow of blood during menstruation, privacy to change the materials, and access to facilities to dispose of used menstrual management materials. It can also include the "broader systemic factors that link menstruation with health, well-being, gender equality, education, equity, empowerment, and rights". Menstrual hygiene management can be particularly challenging for girls and women in developing countries, where clean water and toilet facilities are often inadequate. Menstrual waste is largely ignored in schools in developing countries, despite it being a significant problem. Menstruation can be a barrier to education for many girls, as a lack of effective sanitary products restricts girls' involvement in educational and social activities.

Period underwear are absorbent garments designed to be worn during menstruation. Period underwear is designed like conventional underwear but it is made up of highly absorbent fabrics to soak up menstrual blood. Most commercially manufactured period underwear makes use of microfiber polyester fabric. It is recommended that period underwear should be changed every 8-12 hours to avoid leakage and infection.

Period poverty is a term used to describe a lack of access to proper menstrual products and the education needed to use them effectively. In total, there are around 500 million women and girls that cannot manage their periods safely due to lack of menstrual products and for fear of shame. The American Medical Women's Association defines period poverty as "the inadequate access to menstrual hygiene tools and educations, including but not limited to sanitary products, washing facilities, and waste management". The lack of access to menstrual hygiene products can cause physical health problems, such as infections and reproductive tract complications, and can have negative social and psychological consequences, including missed school or work days and stigma.