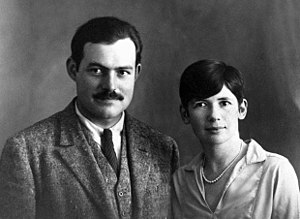

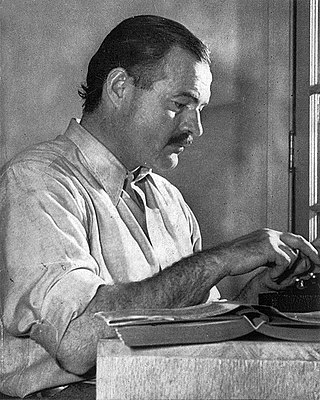

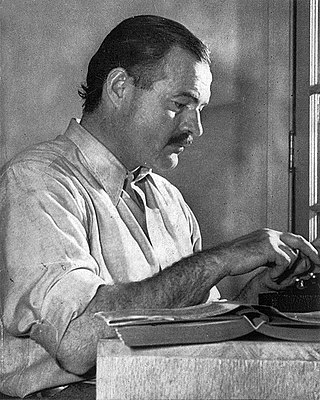

Ernest Miller Hemingway was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which included his iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fiction, while his adventurous lifestyle and public image brought him admiration from later generations. Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, and he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. He published seven novels, six short-story collections, and two nonfiction works. Three of his novels, four short-story collections, and three nonfiction works were published posthumously. Many of his works are considered classics of American literature.

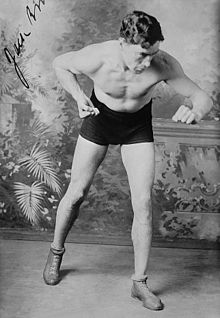

William Harrison "Jack" Dempsey, nicknamed Kid Blackie and The Manassa Mauler, was an American professional boxer who competed from 1914 to 1927, and reigned as the world heavyweight champion from 1919 to 1926. A cultural icon of the 1920s, Dempsey's aggressive fighting style and exceptional punching power made him one of the most popular boxers in history. Many of his fights set financial and attendance records, including the first million-dollar gate. He pioneered the live broadcast of sporting events in general, and boxing matches in particular.

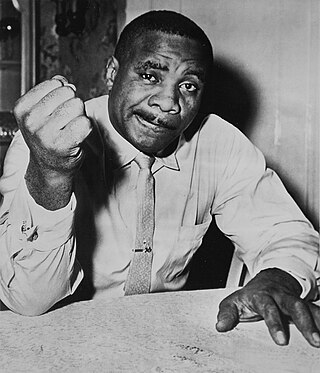

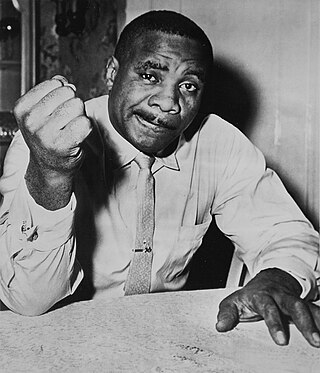

Charles L. "Sonny" Liston was an American professional boxer who competed from 1953 to 1970. A dominant contender of his era, he became the world heavyweight champion in 1962 after knocking out Floyd Patterson in the first round, repeating the knockout the following year in defense of the title; in the latter fight he also became the inaugural WBC heavyweight champion. Often regarded as one of the greatest boxers of all time, Liston was particularly known for his immense strength, formidable jab, long reach, toughness, and is widely regarded as the most intimidating man in the history of the sport.

Stanisław Kiecal, better known in the boxing world as Stanley Ketchel, was an American professional boxer who became one of the greatest World Middleweight Champions in history. He was nicknamed "The Michigan Assassin." He was murdered at a ranch in Conway, Missouri, at the age of 24.

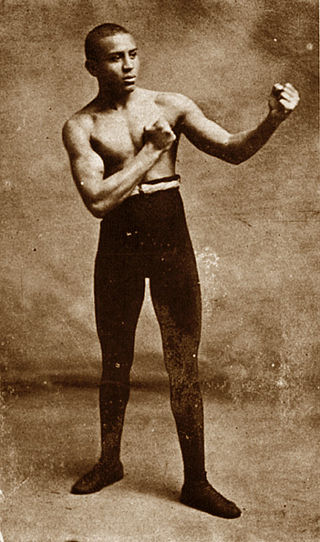

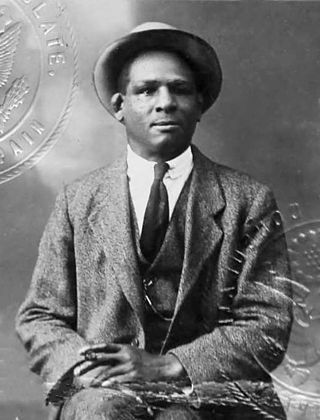

Samuel Edgar Langford, known as the Boston Tar Baby, Boston Terror and Boston Bonecrusher, was a Black Canadian boxing standout of the early part of the 20th century. Called the "Greatest Fighter Nobody Knows", by ESPN, Langford is considered by many boxing historians to be one of the greatest fighters of all time. Originally from Weymouth Falls, a small community in Nova Scotia, he was known as "The Boston Bonecrusher", "The Boston Terror", and his most famous nickname, "The Boston Tar Baby". Langford stood 5 ft 6+1⁄2 in (1.69 m) and weighed 185 lb (84 kg) in his prime. He fought from lightweight to heavyweight and defeated many world champions and legends of the time in each weight class. Considered a devastating puncher even at heavyweight, Langford was rated No. 2 by The Ring on their list of "100 greatest punchers of all time". One boxing historian described Langford as "experienced as a heavyweight James Toney with the punching power of Mike Tyson".

The two fights between Muhammad Ali and Sonny Liston for boxing's World Heavyweight Championship were among the most controversial fights in the sport's history. Sports Illustrated magazine named their first meeting, the Liston–Clay fight, as the fourth greatest sports moment of the twentieth century.

"The Killers" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway, first published in Scribner's Magazine in 1927 and later republished in Men Without Women,Snows of Kilimanjaro, and The Nick Adams Stories. Set in 1920s Summit, Illinois, the story follows recurring Hemingway character Nick Adams as he has a run-in with a pair of hitmen, who are seeking to kill a boxer, in a local restaurant.

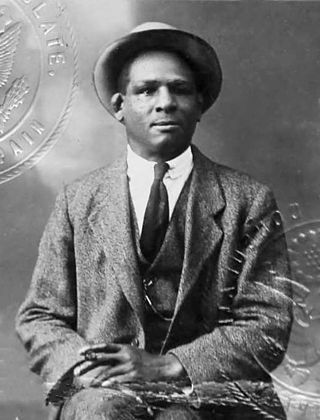

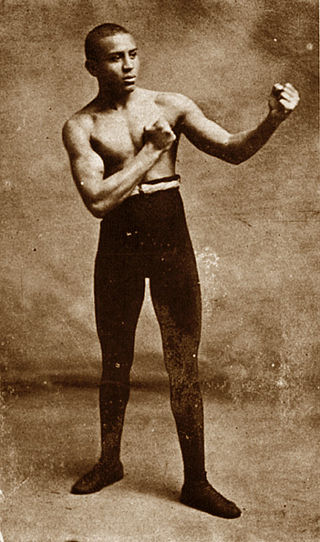

Joe Gans was an American professional boxer. Gans was rated the greatest lightweight boxer of all-time by boxing historian and Ring Magazine founder, Nat Fleischer. Known as the "Old Master", he became the first African-American world boxing champion of the 20th century, reigning continuously as world lightweight champion from 1902 to 1908, defending the title 15 times versus 13 boxers. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1990.

Louis Mbarick Fall, known as Battling Siki, was a Senegalese light heavyweight boxer born in Senegal who fought from 1912 to 1925, and briefly reigned as the World light heavyweight champion after knocking out Georges Carpentier.

Jack Britton was an American boxer who was the first three-time world welterweight boxing champion. Born William J. Breslin in Clinton, New York, his professional career lasted for 25 years beginning in 1905. He holds the world record for the number of title bouts fought in a career with 37, many against his arch-rival Ted "Kid" Lewis, against whom he fought 20 times. Statistical boxing website BoxRec lists Britton as the No. 6 ranked welterweight of all time while The Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleischer placed him at No. 3. He was inducted into the Ring Magazine Hall of Fame in 1960 and the International Boxing Hall of Fame as a first-class member in 1990.

The Harder They Fall is a 1956 American boxing film noir directed by Mark Robson with a screenplay by Philip Yordan, based on Budd Schulberg's 1947 novel. It was Humphrey Bogart's final film role. It received an Oscar nomination for Best Cinematography, Black and White for Burnett Guffey at the 29th Academy Awards.

To Have and Have Not is a 1944 American romantic war adventure film directed by Howard Hawks, loosely based on Ernest Hemingway's 1937 novel of the same name. It stars Humphrey Bogart, Walter Brennan and Lauren Bacall; it also features Dolores Moran, Hoagy Carmichael, Sheldon Leonard, Dan Seymour, and Marcel Dalio. The plot, centered on the romance between a freelancing fisherman in Martinique and a beautiful American drifter, is complicated by the growing French resistance in Vichy France.

The Prizefighter and the Lady is a 1933 pre-Code Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer romance film starring Myrna Loy and the professional boxers Max Baer, Primo Carnera, and Jack Dempsey. The film was adapted for the screen by John Lee Mahin and John Meehan from a story by Frances Marion. Marion was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Writing, Original Story.

Men Without Women (1927) is the second collection of short stories written by American author Ernest Hemingway. The volume consists of 14 stories, 10 of which had been previously published in magazines. It was published in October 1927, with a first print-run of approximately 7600 copies at $2.

Dateline: Toronto is a collection of most of the stories that Ernest Hemingway wrote as a stringer and later staff writer and foreign correspondent for the Toronto Star between 1920 and 1924. The stories were written while he was in his early 20s before he became well-known, and show his development as a writer. The collection was edited by William White, a professor of English literature and journalism at Wayne State University, and a regular contributor to The Hemingway Review.

Rube Ferns was an American boxer of the early 20th century. Nicknamed "The Kansas Rube", he held the World Welterweight Championship in 1900 and 1901. He was formidable and scrappy with a good punch.

Aaron Lister Brown, known professionally as the Dixie Kid, was an American boxer. He was a controversial contender for the World Welterweight Boxing Championship in April 1904.

"Out of Season" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, first published in 1923 in Paris in the privately printed book, Three Stories and Ten Poems. It was included in his next collection of stories, In Our Time, published in New York in 1925 by Boni & Liveright. Set in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, the story is about an expatriate American husband and wife who spend the day fishing, with a local guide. Critical attention focuses chiefly on its autobiographical elements and on Hemingway's claim that it was his first attempt at using the "theory of omission".

Jonathan "Jack" Murdock is a fictional character appearing in American comic books published by Marvel Comics. He was a professional championship Boxer in his day; as well as being the father of Matthew "Matt" Murdock (Daredevil) and his magically created twin brother Michael "Mike" Murdock, and the ex-husband of Maggie Murdock. Jack Murdock was murdered because of the local gangster, The Fixer's men when he refused to throw a fight for him in front of his son Matt, while Jack was working for The Fixer at the time as one of thugs in secret. After his Father is murdered, it inspires Matt to use hyper sense powers along with his Martial Arts training to avenge his father's murder as the Superhero Daredevil. Jack Murdock was created by writer-editor Stan Lee and artist Bill Everett. The character first appeared in Daredevil #1.

Today is Friday is a short, one act play by Ernest Hemingway. The play was first published in pamphlet form in 1926 but became more widely known through its subsequent publication in Hemingway's 1927 short story collection, Men Without Women. The play is a representation of the aftermath of the crucifixion of Jesus, in the form of a conversation between three Roman Soldiers and a Hebrew bartender. It is one of the few dramatic works written by Hemingway.