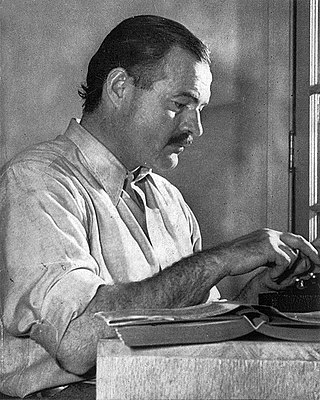

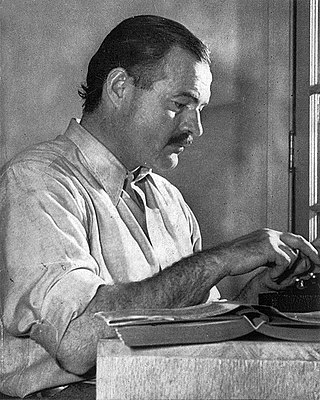

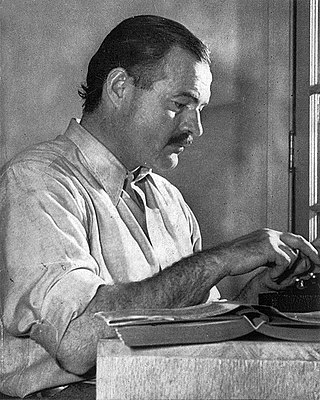

Ernest Miller Hemingway was an American novelist, short-story writer and journalist. Best known for an economical, understated style that significantly influenced later 20th-century writers, he is often romanticized for his adventurous lifestyle, and outspoken and blunt public image. Most of Hemingway's works were published between the mid-1920s and mid-1950s, including seven novels, six short-story collections and two non-fiction works. His writings have become classics of American literature; he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature, while three of his novels, four short-story collections and three nonfiction works were published posthumously.

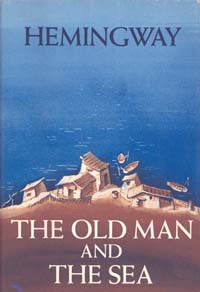

The Old Man and the Sea is a 1952 novella written by the American author Ernest Hemingway. Written between December 1950 and February 1951, it was the last major fictional work Hemingway published during his lifetime. It tells the story of Santiago, an aging fisherman, and his long struggle to catch a giant marlin. The novella was highly anticipated and was released to record sales; the initial critical reception was equally positive, but attitudes have varied significantly since then.

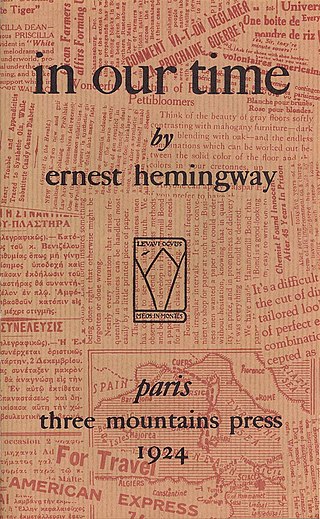

In Our Time is the title of Ernest Hemingway's first collection of short stories, published in 1925 by Boni & Liveright, New York, and of a collection of vignettes published in 1924 in France titled in our time. Its title is derived from the English Book of Common Prayer, "Give peace in our time, O Lord".

Winner Take Nothing is a 1933 collection of short stories by Ernest Hemingway. Hemingway's third and final collection of stories, it was published four years after A Farewell to Arms (1929), and a year after his non-fiction book about bullfighting, Death in the Afternoon (1932).

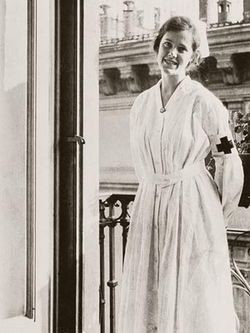

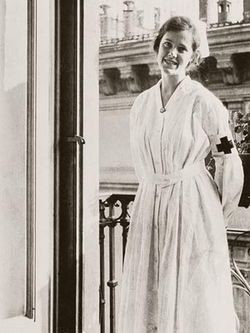

Agnes Hannah von Kurowsky Stanfield was an American nurse who inspired the character "Catherine Barkley" in Ernest Hemingway's 1929 novel A Farewell to Arms.

The iceberg theory or theory of omission is a writing technique coined by American writer Ernest Hemingway. As a young journalist, Hemingway had to focus his newspaper reports on immediate events, with very little context or interpretation. When he became a writer of short stories, he retained this minimalistic style, focusing on surface elements without explicitly discussing underlying themes. Hemingway believed the deeper meaning of a story should not be evident on the surface, but should shine through implicitly.

The Lamentation of Christ is a painting of about 1480 by the Italian Renaissance artist Andrea Mantegna. While the dating of the piece is debated, it was completed between 1475 and 1501, probably in the early 1480s. It portrays the body of Christ supine on a marble slab. He is watched over by the Virgin Mary, Saint John and St. Mary Magdalene weeping for his death.

"Big Two-Hearted River" is a two-part short story written by American author Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 Boni & Liveright edition of In Our Time, the first American volume of Hemingway's short stories. It features a single protagonist, Hemingway's recurrent autobiographical character Nick Adams, whose speaking voice is heard just three times. The story explores the destructive qualities of war which is countered by the healing and regenerative powers of nature. When it was published, critics praised Hemingway's sparse writing style and it became an important work in his canon.

In Love and War is a 1996 romantic drama film based on the book, Hemingway in Love and War by Henry S. Villard and James Nagel. The film stars Sandra Bullock, Chris O'Donnell, Mackenzie Astin, and Margot Steinberg. Its action takes place during the First World War and is based on the wartime experiences of the writer Ernest Hemingway. It was directed by Richard Attenborough. The film was entered into the 47th Berlin International Film Festival.

"The Three-Day Blow" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 New York edition of In Our Time, by Boni & Liveright. The story is the fourth in the collection to feature Nick Adams, Hemingway's autobiographical alter ego.

"Indian Camp" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. The story was first published in 1924 in Ford Madox Ford's literary magazine Transatlantic Review in Paris and republished by Boni & Liveright in Hemingway's first American volume of short stories In Our Time in 1925. Hemingway's semi-autobiographical character Nick Adams—a child in this story—makes his first appearance in "Indian Camp", told from his point of view.

"The Battler" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 New York edition of In Our Time, by Boni & Liveright. The story is the fifth in the collection to feature Nick Adams, Hemingway's autobiographical alter ego.

"A Very Short Story" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. It was first published as a vignette, or chapter, in the 1924 Paris edition titled In Our Time, and later rewritten and added to Hemingway's first American short story collection In Our Time, published by Boni & Liveright in 1925.

"The Doctor and the Doctor's Wife" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway, published in the 1925 New York edition of In Our Time, by Boni & Liveright. The story is the second in the collection to feature Nick Adams, Hemingway's autobiographical alter ego. "The Doctor and the Doctor's Wife" follows "Indian Camp" in the collection, includes elements of the same style and themes, yet is written in counterpoint to the first story.

"Cross Country Snow" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. The story was first published in 1924 in Ford Madox Ford's literary magazine Transatlantic Review in Paris and republished by Boni & Liveright in Hemingway's first American volume of short stories In Our Time in 1925. The story features Hemingway's recurrent autobiographical character Nick Adams and explores the regenerative powers of nature and the joy of skiing.

"My Old Man" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, published in his 1923 book Three Stories and Ten Poems, which published by a small Paris imprint. The story was also included in his next collection of stories, In Our Time, published in New York in 1925 by Boni & Liveright. The story tells of a boy named Joe whose father is a steeplechase jockey, and is narrated from Joe's point-of-view.

"Out of Season" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, first published in 1923 in Paris in the privately printed book, Three Stories and Ten Poems. It was included in his next collection of stories, In Our Time, published in New York in 1925 by Boni & Liveright. Set in Cortina d'Ampezzo, Italy, the story is about an expatriate American husband and wife who spend the day fishing, with a local guide. Critical attention focuses chiefly on its autobiographical elements and on Hemingway's claim that it was his first attempt at using the "theory of omission".

"On the Quai at Smyrna" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway, first published in the 1930 Scribner's edition of the In Our Time collection of short stories, then titled "Introduction by the author". Accompanying it was an introduction by Edmund Wilson. Considered little more than a vignette, the piece was renamed "On the Quai at Smyrna" in the 1938 publication of The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories. When In Our Time was reissued in 1955, it led with "On the Quai at Smyrna", replacing "Indian Camp" as the first story of the collection.

"Mr. and Mrs. Elliot" is a short story written by Ernest Hemingway. The story was first published in The Little Review in 1924 and republished by Boni & Liveright in Hemingway's first American volume of short stories, In Our Time, in 1925.

Today is Friday is a short, one act play by Ernest Hemingway. The play was first published in pamphlet form in 1926 but became more widely known through its subsequent publication in Hemingway's 1927 short story collection, Men Without Women. The play is a representation of the aftermath of the crucifixion of Jesus, in the form of a conversation between three Roman Soldiers and a Hebrew bartender. It is one of the few dramatic works written by Hemingway.