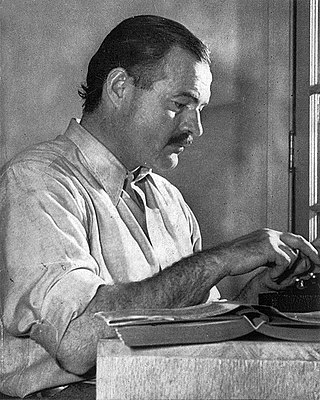

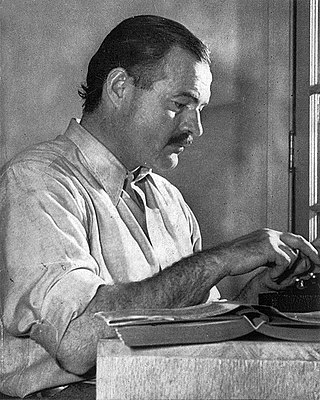

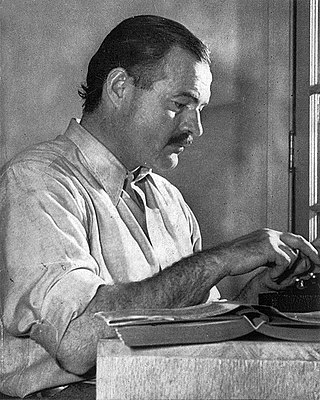

Ernest Miller Hemingway was an American novelist, short-story writer, and journalist. His economical and understated style—which included his iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fiction, while his adventurous lifestyle and public image brought him admiration from later generations. Hemingway produced most of his work between the mid-1920s and the mid-1950s, and he was awarded the 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature. He published seven novels, six short-story collections, and two nonfiction works. Three of his novels, four short-story collections, and three nonfiction works were published posthumously. Many of his works are considered classics of American literature.

Adventures of Huckleberry Finn is a novel by American author Mark Twain, which was first published in the United Kingdom in December 1884 and in the United States in February 1885.

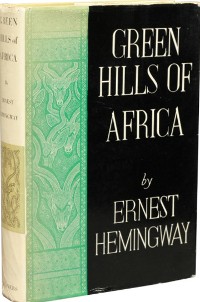

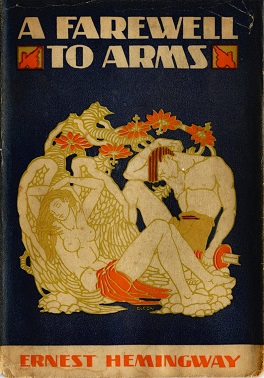

A Farewell to Arms is a novel by American writer Ernest Hemingway, set during the Italian campaign of World War I. First published in 1929, it is a first-person account of an American, Frederic Henry, serving as a lieutenant in the ambulance corps of the Italian Army. The novel describes a love affair between the expatriate from America and an English nurse, Catherine Barkley.

The Dangerous Summer is a nonfiction book by Ernest Hemingway published posthumously in 1985 and written in 1959 and 1960. The book describes the rivalry between bullfighters Luis Miguel Dominguín and his brother-in-law, Antonio Ordóñez, during the "dangerous summer" of 1959. It has been cited as Hemingway's last book.

"The Snows of Kilimanjaro" is a short story by American author Ernest Hemingway first published in August 1936, in Esquire magazine. It was republished in The Fifth Column and the First Forty-Nine Stories in 1938, The Snows of Kilimanjaro and Other Stories in 1961, and is included in The Complete Short Stories of Ernest Hemingway: The Finca Vigía Edition (1987).

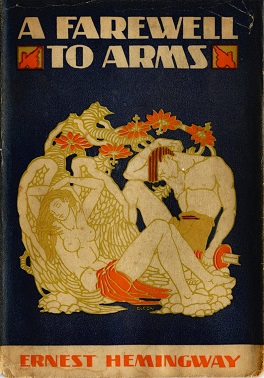

True at First Light is a book by American novelist Ernest Hemingway about his 1953–54 East African safari with his fourth wife Mary, released posthumously in his centennial year in 1999. The book received mostly negative or lukewarm reviews from the popular press and sparked a literary controversy regarding how, and whether, an author's work should be reworked and published after his death. Unlike critics in the popular press, Hemingway scholars generally consider True at First Light to be complex and a worthy addition to his canon of later fiction.

"The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" is a short story by Ernest Hemingway. Set in Africa, it was published in the September 1936 issue of Cosmopolitan magazine concurrently with "The Snows of Kilimanjaro". The story was eventually adapted to the screen as the Zoltan Korda film The Macomber Affair (1947).

Baron Bror Fredrik von Blixen-Finecke was a Swedish nobleman, writer, and African professional hunter and guide on big-game hunts. He was married to Karen Blixen from 1914 to 1925.

White hunter is a literary term used for professional big game hunters of European descent, from all over the world, who plied their trade in Africa, especially during the first half of the 20th century. The activity continues in the dozen African countries which still permit big-game hunting. White hunters derived their income from organizing and leading safaris for paying clients, or from the sale of ivory.

Big-game hunting is the hunting of large game animals for meat, commercially valuable by-products, trophy/taxidermy, or simply just for recreation ("sporting"). The term is often associated with the hunting of Africa's "Big Five" games, and with tigers and rhinoceroses on the Indian subcontinent.

The Ernest Hemingway House was the residence of American writer Ernest Hemingway in the 1930s. The house is situated on the island of Key West in Florida. It is at 907 Whitehead Street, across from the Key West Lighthouse, close to the southern coast of the island. Due to its association with Hemingway, the property is the most popular tourist attraction in Key West. It is also famous for its large population of so-called Hemingway cats, many of which are polydactyl.

Under Kilimanjaro is a non-fiction novel by Ernest Hemingway, edited and published posthumously by Robert W. Lewis and Robert E. Fleming. It is based upon journals that he wrote while he was on his last safari. It is a longer and re-edited version of True at First Light.

Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) was an American novelist, short-story writer, journalist, and sportsman. His economical and understated style—which he termed the iceberg theory—had a strong influence on 20th-century fiction. Many of his works are considered classics of American literature.

Patrick Miller Hemingway is an American wildlife manager and writer who is novelist Ernest Hemingway's second son, and the first born to Hemingway's second wife Pauline Pfeiffer. During his childhood he travelled frequently with his parents, and then attended Harvard University, graduated in 1950, and shortly thereafter moved to East Africa where he lived for 25 years. In Tanzania, Patrick was a professional big-game hunter and for over a decade he owned a safari business. In the 1960s he was appointed by the United Nations to the Wildlife Management College in Tanzania as a teacher of conservation and wildlife. In the 1970s he moved to Montana where he managed the intellectual property of his father's estate. He edited his father's unpublished novel about a 1950s safari to Africa and published it with the title True at First Light (1999).

Philip Hope Percival (1886–1966) was a renowned white hunter and early safari guide in colonial Kenya. During his career, he guided Theodore Roosevelt, Baron Rothschild, and Ernest Hemingway on African hunts. Hemingway modelled the fictional hunter Robert Wilson in his story "The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber" after Percival. Percival also worked with well-known white hunters like Bror von Blixen-Finecke and mentored Sydney Downey and Harry Selby, and was known in African hunting circles as the "Dean of Hunters".

Sy Montgomery is an American naturalist, author and scriptwriter who writes for children as well as adults.

Ernest Hemingway owned a 38-foot (12 m) fishing boat named Pilar. It was acquired in April 1934 from Wheeler Shipbuilding in Brooklyn, New York, for $7,495. "Pilar" was a nickname for Hemingway's second wife, Pauline, and also the name of the woman leader of the partisan band in his 1940 novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls. Hemingway regularly fished off the boat in the waters of Key West, Florida, Marquesas Keys, and the Gulf Stream off the Cuban coast. He made three trips with the boat to the Bimini islands, wherein his fishing, drinking, and fighting exploits drew much attention and remain part of the islands' history. In addition to fishing trips on Pilar, Hemingway contributed to scientific research, including collaboration with the Smithsonian Institution. Several of Hemingway's books were influenced by time spent on the boat, most notably, The Old Man and the Sea (1953) and Islands in the Stream (1970). The yacht also inspired the name of Playa Pilar on Cayo Guillermo. A smaller replica of the boat is depicted in the opening and other scenes in the 2012 film Hemingway & Gellhorn.

Hans CoryOBE was a self-taught British social anthropologist of Austrian descent, farmer and sociologist with a special interest in traditional lifestyles of ethnic groups in former Tanganyika, now Tanzania. Little is known about his childhood and youth in Vienna as well as about his life before the First World War in colonial German East Africa.

The 1954 Nobel Prize in Literature was awarded to the American author Ernest Hemingway (1899–1961) "for his mastery of the art of narrative, most recently demonstrated in The Old Man and the Sea, and for the influence that he has exerted on contemporary style."