Homo habilis is an extinct species of archaic human from the Early Pleistocene of East and South Africa about 2.8 million years ago to 1.65 million years ago (mya). Upon species description in 1964, H. habilis was highly contested, with many researchers recommending it be synonymised with Australopithecus africanus, the only other early hominin known at the time, but H. habilis received more recognition as time went on and more relevant discoveries were made. By the 1980s, H. habilis was proposed to have been a human ancestor, directly evolving into Homo erectus which directly led to modern humans. This viewpoint is now debated. Several specimens with insecure species identification were assigned to H. habilis, leading to arguments for splitting, namely into "H. rudolfensis" and "H. gautengensis" of which only the former has received wide support.

Paranthropus is a genus of extinct hominin which contains two widely accepted species: P. robustus and P. boisei. However, the validity of Paranthropus is contested, and it is sometimes considered to be synonymous with Australopithecus. They are also referred to as the robust australopithecines. They lived between approximately 2.9 and 1.2 million years ago (mya) from the end of the Pliocene to the Middle Pleistocene.

In anatomy, the atlas (C1) is the most superior (first) cervical vertebra of the spine and is located in the neck.

Australopithecus is a genus of early hominins that existed in Africa during the Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. The genera Homo, Paranthropus, and Kenyanthropus evolved from some Australopithecus species. Australopithecus is a member of the subtribe Australopithecina, which sometimes also includes Ardipithecus, though the term "australopithecine" is sometimes used to refer only to members of Australopithecus. Species include A. garhi, A. africanus, A. sediba, A. afarensis, A. anamensis, A. bahrelghazali and A. deyiremeda. Debate exists as to whether some Australopithecus species should be reclassified into new genera, or if Paranthropus and Kenyanthropus are synonymous with Australopithecus, in part because of the taxonomic inconsistency.

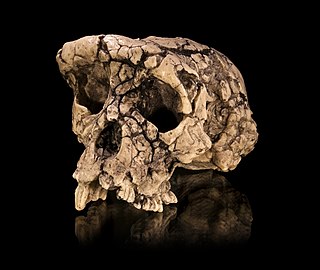

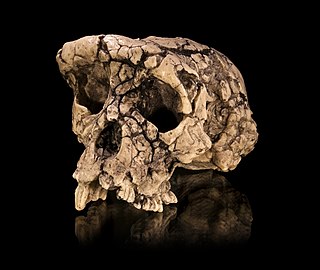

Sahelanthropus tchadensis is an extinct species of hominid dated to about 7 million years ago, during the Miocene epoch. The species, and its genus Sahelanthropus, was announced in 2002, based mainly on a partial cranium, nicknamed Toumaï, discovered in northern Chad.

The occipital bone is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput. It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobes of the cerebrum. At the base of the skull in the occipital bone, there is a large oval opening called the foramen magnum, which allows the passage of the spinal cord.

Meganthropus is an extinct genus of non-hominin hominid ape, known from the Pleistocene of Indonesia. It is known from a series of large jaw and skull fragments found at the Sangiran site near Surakarta in Central Java, Indonesia, alongside several isolated teeth. The genus has a long and convoluted taxonomic history. The original fossils were ascribed to a new species, Meganthropus palaeojavanicus, and for a long time was considered invalid, with the genus name being used as an informal name for the fossils.

Paleoanthropology or paleo-anthropology is a branch of paleontology and anthropology which seeks to understand the early development of anatomically modern humans, a process known as hominization, through the reconstruction of evolutionary kinship lines within the family Hominidae, working from biological evidence and cultural evidence.

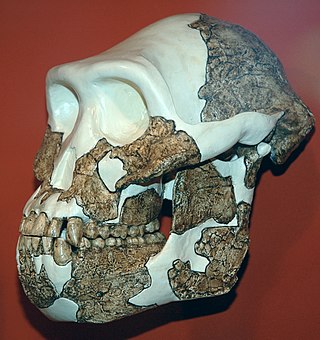

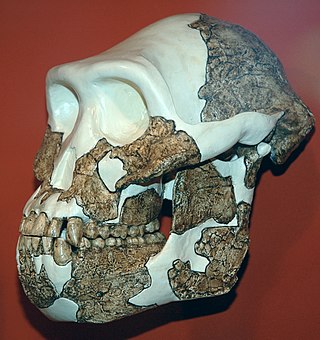

Mrs. Ples is the popular nickname for the most complete skull of an Australopithecus africanus ever found in South Africa. Many Australopithecus fossils have been found near Sterkfontein, about 40 kilometres (25 mi) northwest of Johannesburg, in a region of Gauteng now designated as the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site. Mrs. Ples was discovered by Robert Broom and John T. Robinson on April 18, 1947. Because of Broom's use of dynamite and pickaxe while excavating, Mrs. Ples's skull was blown into pieces and some fragments are missing. Nonetheless, Mrs./Mr. Ples is one of the most "perfect" pre-human skulls ever found. The skull is currently held at the Ditsong National Museum of Natural History in Pretoria.

Australopithecus africanus is an extinct species of australopithecine which lived between about 3.3 and 2.1 million years ago in the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of South Africa. The species has been recovered from Taung, Sterkfontein, Makapansgat, and Gladysvale. The first specimen, the Taung child, was described by anatomist Raymond Dart in 1924, and was the first early hominin found. However, its closer relations to humans than to other apes would not become widely accepted until the middle of the century because most had believed humans evolved outside of Africa. It is unclear how A. africanus relates to other hominins, being variously placed as ancestral to Homo and Paranthropus, to just Paranthropus, or to just P. robustus. The specimen "Little Foot" is the most completely preserved early hominin, with 90% of the skeleton intact, and the oldest South African australopith. However, it is controversially suggested that it and similar specimens be split off into "A. prometheus".

Homo rhodesiensis is the species name proposed by Arthur Smith Woodward (1921) to classify Kabwe 1, a Middle Stone Age fossil recovered from Broken Hill mine in Kabwe, Northern Rhodesia. In 2020, the skull was dated to 324,000 to 274,000 years ago. Other similar older specimens also exist.

Australopithecus anamensis is a hominin species that lived approximately between 4.2 and 3.8 million years ago and is the oldest known Australopithecus species, living during the Plio-Pleistocene era.

Paranthropus aethiopicus is an extinct species of robust australopithecine from the Late Pliocene to Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.7–2.3 million years ago. However, it is much debated whether or not Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and is synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus aethiopicus. Whatever the case, it is considered to have been the ancestor of the much more robust P. boisei. It is debated if P. aethiopicus should be subsumed under P. boisei, and the terms P. boisei sensu lato and P. boisei sensu stricto can be used to respectively include and exclude P. aethiopicus from P. boisei.

Paranthropus robustus is a species of robust australopithecine from the Early and possibly Middle Pleistocene of the Cradle of Humankind, South Africa, about 2.27 to 0.87 million years ago. It has been identified in Kromdraai, Swartkrans, Sterkfontein, Gondolin, Cooper's, and Drimolen Caves. Discovered in 1938, it was among the first early hominins described, and became the type species for the genus Paranthropus. However, it has been argued by some that Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus robustus.

Paranthropus boisei is a species of australopithecine from the Early Pleistocene of East Africa about 2.5 to 1.15 million years ago. The holotype specimen, OH 5, was discovered by palaeoanthropologist Mary Leakey in 1959 at Olduvai Gorge, Tanzania and described by her husband Louis a month later. It was originally placed into its own genus as "Zinjanthropus boisei", but is now relegated to Paranthropus along with other robust australopithecines. However, it is also argued that Paranthropus is an invalid grouping and synonymous with Australopithecus, so the species is also often classified as Australopithecus boisei.

Orthograde is a term derived from Greek ὀρθός, orthos + Latin gradi that describes a manner of walking which is upright, with the independent motion of limbs. Both New and Old World monkeys are primarily arboreal, and they have a tendency to walk with their limbs swinging in parallel to one another. This differs from the manner of walking demonstrated by the apes.

The lateral parts of the occipital bone are situated at the sides of the foramen magnum; on their under surfaces are the condyles for articulation with the superior facets of the atlas.

The evolution of human bipedalism, which began in primates approximately four million years ago, or as early as seven million years ago with Sahelanthropus, or approximately twelve million years ago with Danuvius guggenmosi, has led to morphological alterations to the human skeleton including changes to the arrangement, shape, and size of the bones of the foot, hip, knee, leg, and the vertebral column. These changes allowed for the upright gait to be overall more energy efficient in comparison to quadrupeds. The evolutionary factors that produced these changes have been the subject of several theories that correspond with environmental changes on a global scale.

The endocranium in comparative anatomy is a part of the skull base in vertebrates and it represents the basal, inner part of the cranium. The term is also applied to the outer layer of the dura mater in human anatomy.

In brain anatomy, the lunate sulcus or simian sulcus, also known as the sulcus lunatus, is a fissure in the occipital lobe variably found in humans and more often larger when present in apes and monkeys. The lunate sulcus marks the transition between V1 and V2.