The Salt River is a river in Gila and Maricopa counties in Arizona, United States, that is the largest tributary of the Gila River. The river is about 200 miles (320 km) long. Its drainage basin covers about 13,700 square miles (35,000 km2). The longest of the Salt River's many tributaries is the 195-mile (314 km) Verde River. The Salt's headwaters tributaries, the Black River and East Fork, increase the river's total length to about 300 miles (480 km). The name Salt River comes from the river's course over large salt deposits shortly after the merging of the White and Black Rivers.

The Salmon River, also known as "The River of No Return", is a river located in the U.S. state of Idaho in the western United States. It flows for 425 miles (685 km) through central Idaho, draining a rugged, thinly populated watershed of 14,000 square miles (36,000 km2). The river drops more than 7,000 feet (2,100 m) from its headwaters, near Galena Summit above the Sawtooth Valley in the Sawtooth National Recreation Area, to its confluence with the Snake River. Measured at White Bird, its average discharge is 11,060 cubic feet per second. The Salmon River is the longest undammed river in the contiguous United States.

The John Day River is a tributary of the Columbia River, approximately 284 miles (457 km) long, in northeastern Oregon in the United States. It is known as the Mah-Hah River by the Cayuse people. Undammed along its entire length, the river is the fourth longest free-flowing river in the contiguous United States. There is extensive use of its waters for irrigation. Its course furnishes habitat for diverse species, including wild steelhead and Chinook salmon runs. However, the steelhead populations are under federal Endangered Species Act (ESA) protections, and the Chinook salmon have been proposed for such protection.

The Kern River, previously Rio de San Felipe, later La Porciuncula, is an Endangered, Wild and Scenic river in the U.S. state of California, approximately 165 miles (270 km) long. It drains an area of the southern Sierra Nevada mountains northeast of Bakersfield. Fed by snowmelt near Mount Whitney, the river passes through scenic canyons in the mountains and is a popular destination for whitewater rafting and kayaking. It is the southernmost major river system in the Sierra Nevada, and is the only major river in the Sierra that drains in a southerly direction.

The Verde River is a major tributary of the Salt River in the U.S. state of Arizona. It is about 170 miles (270 km) long and carries a mean flow of 602 cubic feet per second (17.0 m3/s) at its mouth. It is one of the largest perennial streams in Arizona.

The Tonto National Forest, encompassing 2,873,200 acres, is the largest of the six national forests in Arizona and is the ninth largest national forest in the United States. The forest has diverse scenery, with elevations ranging from 1,400 feet in the Sonoran Desert to 7,400 feet in the ponderosa pine forests of the Mogollon Rim. The Tonto National Forest is also the most visited "urban" forest in the United States.

The Coconino National Forest is a 1.856-million acre United States National Forest located in northern Arizona in the vicinity of Flagstaff, with elevations ranging from 2,600 feet to the highest point in Arizona at 12,633 feet. Originally established in 1898 as the "San Francisco Mountains National Forest Reserve", the area was designated a U.S. National Forest by Pres. Theodore Roosevelt on July 2, 1908, when the San Francisco Mountains National Forest Reserve was merged with lands from other surrounding forest reserves to create the Coconino National Forest. Today, the Coconino National Forest contains diverse landscapes, including deserts, ponderosa pine forests, flatlands, mesas, alpine tundra, and ancient volcanic peaks. The forest surrounds the towns of Sedona and Flagstaff and borders four other national forests; the Kaibab National Forest to the west and northwest, the Prescott National Forest to the southwest, the Tonto National Forest to the south, and the Apache-Sitgreaves National Forest to the southeast. The forest contains all or parts of nine designated wilderness areas, including the Kachina Peaks Wilderness, which includes the summit of the San Francisco Peaks. The headquarters are in Flagstaff. The Coconino National Forest consists of three districts: Flagstaff Ranger District, Mogollon Rim Ranger District, and Red Rock Ranger District, which have local ranger district offices in Flagstaff, Happy Jack, and Sedona.

The Mokelumne River is a 95-mile (153 km)-long river in northern California in the United States. The river flows west from a rugged portion of the central Sierra Nevada into the Central Valley and ultimately the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta, where it empties into the San Joaquin River-Stockton Deepwater Shipping Channel. Together with its main tributary, the Cosumnes River, the Mokelumne drains 2,143 square miles (5,550 km2) in parts of five California counties. Measured to its farthest source at the head of the North Fork, the river stretches for 157 miles (253 km).

The Hells Canyon Wilderness is a wilderness area in the western United States, in Idaho and Oregon. Created 49 years ago in 1975, the Wilderness is managed by both the U.S. Bureau of Land Management and the U.S. Forest Service and contains some of the most spectacular sections of the Snake River as it winds its way through Hells Canyon, North America's deepest river gorge and one of the deepest gorges on Earth. The Oregon Wilderness Act of 1984 added additional acreage and currently the area protects a total area of 217,927 acres (88,192 ha). It lies entirely within the Hells Canyon National Recreation Area except for a small 946-acre (383 ha) plot in southeastern Wallowa County, Oregon which is administered by the Bureau of Land Management. The area that is administered by the Forest Service consists of portions of the Wallowa, Nez Perce, Payette, and Whitman National Forests.

The Gila National Forest is a United States National Forest in New Mexico. Established in 1905, it now covers approximately 2,710,659 acres (10,969.65 km2), making it the sixth largest National Forest in the continental United States. The Forest administration also manage the part of the Apache National Forest in New Mexico which covers 614,202 acres for a total of 3.3 million acres managed by the Gila National Forest. Within the forest, the Gila Wilderness was established in 1924 as the US's first designated wilderness. The Aldo Leopold Wilderness and Blue Range Wilderness are also found within its borders. The Blue Range Primitive Area lies within Arizona in the neighboring Apache National Forest.

Sespe Creek is a stream, some 61 miles (98 km) long, in Ventura County, southern California, in the Western United States. The creek starts at Potrero Seco in the eastern Sierra Madre Mountains, and is formed by more than thirty tributary streams of the Sierra Madre and Topatopa Mountains, before it empties into the Santa Clara River in Fillmore.

Oak Creek Canyon is a river gorge located in northern Arizona between the cities of Flagstaff and Sedona. The canyon is often described as a smaller cousin of the Grand Canyon because of its scenic beauty. State Route 89A enters the canyon on its north end via a series of hairpin turns before traversing the bottom of the canyon for about 13 miles (21 km) until the highway enters the town of Sedona.

Sycamore Canyon is the second largest canyon in the Arizona redrock country, after Oak Creek Canyon. The 21-mile (34 km) long scenic canyon reaches a maximum width of about 7 miles (11 km). It is in North Central Arizona bordering and below the Mogollon Rim, and is located west and northwest of Sedona in Yavapai and Coconino counties.

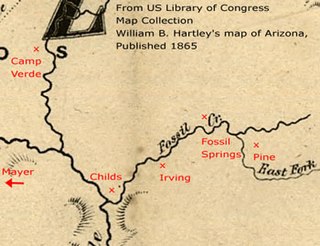

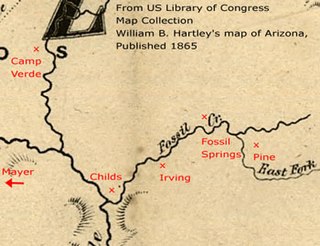

Childs-Irving Hydroelectric Facilities consisted of two 20th-century power plants, a dam, and related infrastructure along or near Fossil Creek in the U.S. state of Arizona. The complex was named an Historic Mechanical Engineering Landmark in 1971 and was added to the National Register of Historic Places 20 years later. Decommissioned in 2005, the plants no longer produce electricity, and much of the infrastructure—including the dam, the Irving Power Plant, and thousands of feet of concrete flumes—have been removed, and the creek's original flow has been restored.

Sycamore Canyon Wilderness is a 56,000-acre wilderness area in the Coconino, Kaibab and Prescott national forests in the U.S. state of Arizona. Encompassing Sycamore Canyon and its surrounds from south of Williams to the confluence of Sycamore Creek with the Verde River, the wilderness is about 40 miles (64 km) southwest of Flagstaff. The canyon is one of several in Arizona that cut through the Mogollon Rim. Relevant United States Geological Survey (USGS) map quadrangles are Davenport Hill, White Horse Lake, May Tank Pocket, Perkinsville, Sycamore Basin, and Clarkdale. Red Rock-Secret Mountain Wilderness borders Sycamore Canyon Wilderness on the east.

The Wild Rogue Wilderness is a wilderness area surrounding the 84-mile (135 km) Wild and Scenic portion of the Rogue River in southwestern Oregon, U.S. to protect the watershed. The wilderness was established in 1978 and now comprises 35,818 acres (14,495 ha). Because it spans part of the Rogue River-Siskiyou National Forest and the Medford district of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), the Wild Rogue Wilderness is administered by both the BLM and the Forest Service.

The Wenaha River is a tributary of the Grande Ronde River, about 22 miles (35 km) long, in the U.S. state of Oregon. The river begins at the confluence of its north and south forks in the Blue Mountains and flows east through the Wenaha–Tucannon Wilderness to meet the larger river at the small settlement of Troy. A designated Wild and Scenic River for its entire length, the stream flows wholly within Wallowa County.

The North Fork Malheur River is a 59-mile (95 km) tributary of the Malheur River in eastern Oregon in the United States. Rising in Big Cow Burn in the Blue Mountains, it flows generally south to join the larger river at Juntura. The upper 25.5 miles (41.0 km) of the river have been designated Wild and Scenic. This part of the river basin offers camping, hiking, and fishing opportunities in a remote forest setting. The lower river passes through Beulah Reservoir, which stores water for irrigation and has facilities for boaters.

The Matilija Wilderness is a 29,207-acre (11,820 ha) wilderness area in Ventura and Santa Barbara Counties, Southern California. It is managed by the U.S. Forest Service, being situated within the Ojai Ranger District of the Los Padres National Forest. It is located adjacent to the Dick Smith Wilderness to the northwest and the Sespe Wilderness to the northeast, although it is much smaller than either one. The Matilija Wilderness was established in 1992 in part to protect California condor habitat.