In nutrition, biology, and chemistry, fat usually means any ester of fatty acids, or a mixture of such compounds, most commonly those that occur in living beings or in food.

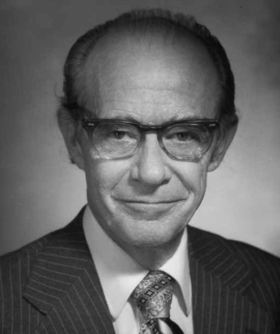

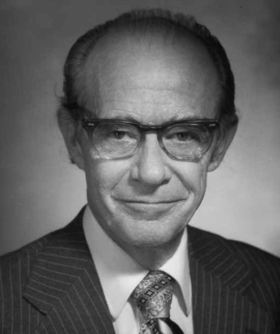

Ancel Benjamin Keys was an American physiologist who studied the influence of diet on health. In particular, he hypothesized that replacing dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduced cardiovascular heart disease. Modern dietary recommendations by health organizations, systematic reviews, and national health agencies corroborate this.

A saturated fat is a type of fat in which the fatty acid chains have all single bonds between the carbon atoms. A fat known as a glyceride is made of two kinds of smaller molecules: a short glycerol backbone and fatty acids that each contain a long linear or branched chain of carbon (C) atoms. Along the chain, some carbon atoms are linked by single bonds (-C-C-) and others are linked by double bonds (-C=C-). A double bond along the carbon chain can react with a pair of hydrogen atoms to change into a single -C-C- bond, with each H atom now bonded to one of the two C atoms. Glyceride fats without any carbon chain double bonds are called saturated because they are "saturated with" hydrogen atoms, having no double bonds available to react with more hydrogen.

The Mediterranean diet is a diet inspired by the eating habits and traditional food typical of southern Spain, southern Italy, and Crete, and formulated in the early 1960s. It is distinct from Mediterranean cuisine, which covers the actual cuisines of the Mediterranean countries, and from the Atlantic diet of northwestern Spain and Portugal. While inspired by a specific time and place, the "Mediterranean diet" was later refined based on the results of multiple scientific studies.

Cardiovascular disease (CVD) is any disease involving the heart or blood vessels. CVDs constitute a class of diseases that includes: coronary artery diseases, heart failure, hypertensive heart disease, rheumatic heart disease, cardiomyopathy, arrhythmia, congenital heart disease, valvular heart disease, carditis, aortic aneurysms, peripheral artery disease, thromboembolic disease, and venous thrombosis.

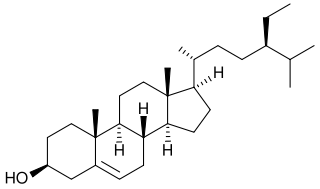

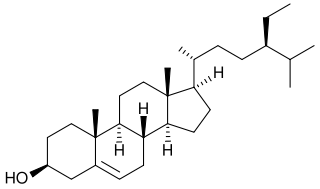

Hypercholesterolemia, also called high cholesterol, is the presence of high levels of cholesterol in the blood. It is a form of hyperlipidemia, hyperlipoproteinemia, and dyslipidemia.

Stanol esters is a heterogeneous group of chemical compounds known to reduce the level of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol in blood when ingested, though to a much lesser degree than prescription drugs such as statins. The starting material is phytosterols from plants. These are first hydrogenated to give a plant stanol which is then esterified with a mixture of fatty acids also derived from plants. Plant stanol esters are found naturally occurring in small quantities in fruits, vegetables, nuts, seeds, cereals, legumes, and vegetable oils.

A healthy diet is a diet that maintains or improves overall health. A healthy diet provides the body with essential nutrition: fluid, macronutrients such as protein, micronutrients such as vitamins, and adequate fibre and food energy.

Hyperlipidemia is abnormally high levels of any or all lipids or lipoproteins in the blood. The term hyperlipidemia refers to the laboratory finding itself and is also used as an umbrella term covering any of various acquired or genetic disorders that result in that finding. Hyperlipidemia represents a subset of dyslipidemia and a superset of hypercholesterolemia. Hyperlipidemia is usually chronic and requires ongoing medication to control blood lipid levels.

Phytosterols are phytosteroids, similar to cholesterol, that serve as structural components of biological membranes of plants. They encompass plant sterols and stanols. More than 250 sterols and related compounds have been identified. Free phytosterols extracted from oils are insoluble in water, relatively insoluble in oil, and soluble in alcohols.

Benecol is a brand of cholesterol-lowering food products owned by the Finnish company Raisio Group, which owns the trademark.

Nathan Pritikin was an American inventor, engineer, nutritionist and longevity researcher. He promoted the Pritikin diet, a high-carbohydrate low-fat plant-based diet combined with regular aerobic exercise to prevent cardiovascular disease. The Pritikin diet emphasizes the consumption of legumes, whole grains, fresh fruit and vegetables and non-fat dairy products with small amounts of lean meat, fowl and fish.

The Western pattern diet is a modern dietary pattern that is generally characterized by high intakes of pre-packaged foods, refined grains, red meat, processed meat, high-sugar drinks, candy and sweets, fried foods, industrially produced animal products, butter and other high-fat dairy products, eggs, potatoes, corn, and low intakes of fruits, vegetables, whole grains, pasture-raised animal products, fish, nuts, and seeds.

The chronic endothelial injury hypothesis is one of two major mechanisms postulated to explain the underlying cause of atherosclerosis and coronary heart disease (CHD), the other being the lipid hypothesis. Although an ongoing debate involving connection between dietary lipids and CHD sometimes portrays the two hypotheses as being opposed, they are in no way mutually exclusive. Moreover, since the discovery of the role of LDL cholesterol (LDL-C) in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis, the two hypotheses have become tightly linked by a number of molecular and cellular processes.

David Mark Hegsted was an American nutritionist who studied the connections between food consumption and heart disease. His work included studies that showed that consumption of saturated fats led to increases in cholesterol, leading to the development of dietary guidelines intended to help Americans achieve better health through improved food choices.

Canadian health claims by Health Canada, the department of the Government of Canada responsible for national health, has allowed five scientifically verified disease risk reduction claims to be used on food labels and on food advertising. Other countries, including the United States and Great Britain, have approved similar health claims on food labels.

The Seven Countries Study is an epidemiological longitudinal study directed by Ancel Keys at what is today the University of Minnesota Laboratory of Physiological Hygiene & Exercise Science (LPHES). Begun in 1956 with a yearly grant of US$200,000 from the U.S. Public Health Service, the study was first published in 1978 and then followed up on its subjects every five years thereafter.

The Portfolio Diet is a therapeutic plant-based diet created by British researcher David J. Jenkins in 2003 to lower blood cholesterol. The diet emphasizes using a portfolio of foods or food components that have been found to associate with cholesterol lowering to enhance this effect. Soluble fiber, soy protein, plant sterols, and nuts are the four essential components of Portfolio diet. The diet is low in saturated fat, high in fibre. Researchers have found it has comparable blood cholesterol effect to statin treatment.

The Israeli paradox is an apparently paradoxical epidemiological observation that Israeli Jews have a relatively high incidence of coronary heart disease (CHD), despite having a diet relatively low in saturated fats, in apparent contradiction to the widely held belief that the high consumption of such fats is a risk factor for CHD. The paradox is that if the thesis linking saturated fats to CHD is valid, the Israelis ought to have a lower rate of CHD than comparable countries where the per capita consumption of such fats is higher.

Trans fat, also called trans-unsaturated fatty acids, or trans fatty acids, is a type of unsaturated fat that occurs in foods. Trace concentrations of trans fats occur naturally, but large amounts are found in some processed foods. Since consumption of trans fats is unhealthy, artificial trans fats are highly regulated or banned in many nations. However, they are still widely consumed in developing nations, resulting in hundreds of thousands of deaths each year. The World Health Organization (WHO) had set a goal to make the world free from industrially produced trans fat by the end of 2023. The goal was not met, and the WHO announced another goal "for accelerated action till 2025 to complete this effort" along with associated support on 1 February 2024.