Related Research Articles

Ganda or Luganda is a Bantu language spoken in the African Great Lakes region. It is one of the major languages in Uganda and is spoken by more than 5.56 million Baganda and other people principally in central Uganda, including the capital Kampala of Uganda. Typologically, it is an agglutinative, tonal language with subject–verb–object word order and nominative–accusative morphosyntactic alignment.

The Bemba language, ChiBemba, is a Bantu language spoken primarily in north-eastern Zambia by the Bemba people and as a lingua franca by about 18 related ethnic groups.

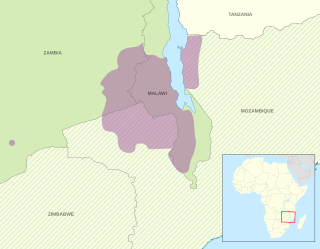

Chewa is a Bantu language spoken in Malawi and a recognised minority in Zambia and Mozambique. The noun class prefix chi- is used for languages, so the language is usually called Chichewa and Chinyanja. In Malawi, the name was officially changed from Chinyanja to Chichewa in 1968 at the insistence of President Hastings Kamuzu Banda, and this is still the name most commonly used in Malawi today. In Zambia, the language is generally known as Nyanja or Cinyanja/Chinyanja '(language) of the lake'.

Koasati is a Native American language of Muskogean origin. The language is spoken by the Coushatta people, most of whom live in Allen Parish north of the town of Elton, Louisiana, though a smaller number share a reservation near Livingston, Texas, with the Alabama people. In 1991, linguist Geoffrey Kimball estimated the number of speakers of the language at around 400 people, of whom approximately 350 live in Louisiana. The exact number of current speakers is unclear, but Coushatta Tribe officials claim that most tribe members over 20 speak Koasati. In 2007, the Coushatta Tribe of Louisiana, in collaboration with McNeese State University and the College of William and Mary, began the Koasati (Coushatta) Language Project as a part of broader language revitalization efforts with National Science Foundation grant money under the Documenting Endangered Languages program.

Taba is a Malayo-Polynesian language of the South Halmahera–West New Guinea group. It is spoken mostly on the islands of Makian, Kayoa and southern Halmahera in North Maluku province of Indonesia by about 20,000 people.

Sesotho nouns signify concrete or abstract concepts in the language, but are distinct from the Sesotho pronouns.

This article presents a brief overview of the grammar of the Sesotho and provides links to more detailed articles.

Abui is a non-Austronesian language of the Alor Archipelago. It is spoken in the central part of Alor Island in Eastern Indonesia, East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) province by the Abui people. The native name in the Takalelang dialect is Abui tanga which literally translates as 'mountain language'.

Adang is a Papuan language spoken on the island of Alor in Indonesia. The language is agglutinative. The Hamap dialect is sometimes treated as a separate language; on the other hand, Kabola, which is sociolinguistically distinct, is sometimes included. Adang, Hamap and Kabola are considered a dialect chain. Adang is endangered as fewer speakers raise their children in Adang, instead opting for Indonesian.

Pashto is an S-O-V language with split ergativity. Adjectives come before nouns. Nouns and adjectives are inflected for gender (masc./fem.), number (sing./plur.), and case. The verb system is very intricate with the following tenses: Present; simple past; past progressive; present perfect; and past perfect. In any of the past tenses, Pashto is an ergative language; i.e., transitive verbs in any of the past tenses agree with the object of the sentence. The dialects show some non-standard grammatical features, some of which are archaisms or descendants of old forms.

Yolmo (Hyolmo) or Helambu Sherpa, is a Tibeto-Burman language of the Hyolmo people of Nepal. Yolmo is spoken predominantly in the Helambu and Melamchi valleys in northern Nuwakot District and northwestern Sindhupalchowk District. Dialects are also spoken by smaller populations in Lamjung District and Ilam District and also in Ramecchap District. It is very similar to Kyirong Tibetan and less similar to Standard Tibetan and Sherpa. There are approximately 10,000 Yolmo speakers, although some dialects have larger populations than others.

The Enggano language, or Engganese, is an Austronesian language spoken on Enggano Island off the southwestern coast of Sumatra, Indonesia.

Farefare or Frafra, also known by the regional name of Gurenne (Gurene), is the language of the Frafra people of northern Ghana, particularly the Upper East Region, and southern Burkina Faso. It is a national language of Ghana, and is closely related to Dagbani and other languages of Northern Ghana, and also related to Mossi, also known as Mooré, the national language of Burkina Faso.

Mungbam is a Southern Bantoid language of the Lower Fungom region of Cameroon. It is traditionally classified as a Western Beboid language, but the language family is disputed. Good et al. uses a more accurate name, the 'Yemne-Kimbi group,' but proposes the term 'Beboid.'

Mavea is an Oceanic language spoken on Mavea Island in Vanuatu, off the eastern coast of Espiritu Santo. It belongs to the North–Central Vanuatu linkage of Southern Oceanic. The total population of the island is approximately 172, with only 34 fluent speakers of the Mavea language reported in 2008.

Mekeo is a language spoken in Papua New Guinea and had 19,000 speakers in 2003. It is an Oceanic language of the Papuan Tip Linkage. The two major villages that the language is spoken in are located in the Central Province of Papua New Guinea. These are named Ongofoina and Inauaisa. The language is also broken up into four dialects: East Mekeo; North West Mekeo; West Mekeo and North Mekeo. The standard dialect is East Mekeo. This main dialect is addressed throughout the article. In addition, there are at least two Mekeo-based pidgins.

Lengo is a Southeast Solomonic language of Guadalcanal.

Longgu (Logu) is a Southeast Solomonic language of Guadalcanal, but originally from Malaita.

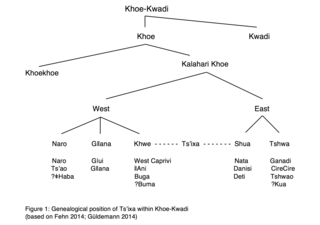

Tsʼixa is a critically endangered African language that belongs to the Kalahari Khoe branch of the Khoe-Kwadi language family. The Tsʼixa speech community consists of approximately 200 speakers who live in Botswana on the eastern edge of the Okavango Delta, in the small village of Mababe. They are a foraging society that consists of the ethnically diverse groups commonly subsumed under the names "San", "Bushmen" or "Basarwa". The most common term of self-reference within the community is Xuukhoe or 'people left behind', a rather broad ethnonym roughly equaling San, which is also used by Khwe-speakers in Botswana. Although the affiliation of Tsʼixa within the Khalari Khoe branch, as well as the genetic classification of the Khoisan languages in general, is still unclear, the Khoisan language scholar Tom Güldemann posits in a 2014 article the following genealogical relationships within Khoe-Kwadi, and argues for the status of Tsʼixa as a language in its own right. The language tree to the right presents a possible classification of Tsʼixa within Khoe-Kwadi:

Swahili is a Bantu language which is native to or mainly spoken in the East African region. It has a grammatical structure that is typical for Bantu languages, bearing all the hallmarks of this language family. These include agglutinativity, a rich array of noun classes, extensive inflection for person, tense, aspect and mood, and generally a subject–verb–object word order.

References

- ↑ Fuliiru at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required)

Joba (Vira) at Ethnologue (18th ed., 2015) (subscription required) - ↑ Jouni Filip Maho, 2009. New Updated Guthrie List Online

- 1 2 3 Van Otterloo, Karen (2011). The Kifuliiru Language: Volume 1. Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-261-6.

- ↑ Van Otterloo, Roger (2011). The Kifuliiru Language: Volume 2. Dallas, TX: SIL International. ISBN 978-1-55671-270-8.

- ↑ This sound is very rare in Fuliiru, and only occurs after other consonants or as the result of a /u/ becoming a glide.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 19.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. xxi.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 2.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. xviii.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 348.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 22.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 21.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 37.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, pp. 31-5.

- 1 2 3 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 11.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 43.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 39.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 44.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 45.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 47.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 49.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 50.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 81.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 84.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 3.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 82.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 90.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 89.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 204.

- 1 2 3 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 205.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 409.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 408.

- 1 2 3 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 206.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 227.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, pp. 209-10.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 238.

- ↑ Nurse, Derek and Maud Devos (2019). “Aspect, Tense and Mood.” The Bantu Languages edited by Mark Van De Velde, et al.: Routledge, pp. 227.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, pp. 229-34.

- 1 2 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 4 Van Otterloo 2011, p. 208.

- ↑ Marlo, Michael R (2014). “The Exceptional Properties of the 1SG and Reflexive Object Markers in Bantu: Syntax, Phonology, or Both?” 45th Annual Conference on African Linguistics [conference presentation]. University of Kansas, p. 7.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 5.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, pp. 208-9.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 13.

- ↑ Nicolle, Steve (2016). “A Linguistic Cycle for Quotatives in Eastern Bantu Languages.” 6th International Conference on Bantu Languages [conference presentation]. Helsinki, Finland, p. 8.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, pp. 114-5.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 509.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 513.

- ↑ Van Otterloo 2011, p. 12.