Environmental determinism is the study of how the physical environment predisposes societies and states towards particular economic or social developmental trajectories. Jared Diamond, Jeffrey Herbst, Ian Morris, and other social scientists sparked a revival of the theory during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. This "neo-environmental determinism" school of thought examines how geographic and ecological forces influence state-building, economic development, and institutions. While archaic versions of the geographic interpretation were used to encourage colonialism and eurocentrism, modern figures like Diamond use this approach to reject the racism in these explanations. Diamond argues that European powers were able to colonize due to unique advantages bestowed by their environment as opposed to any kind of inherent superiority.

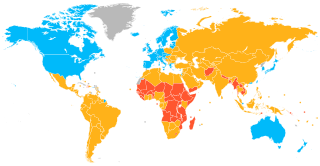

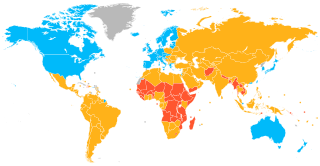

A developing country is a sovereign state with a less developed industrial base and a lower Human Development Index (HDI) relative to other countries. However, this definition is not universally agreed upon. There is also no clear agreement on which countries fit this category. The terms low and middle-income country (LMIC) and newly emerging economy (NEE) are often used interchangeably but refers only to the economy of the countries. The World Bank classifies the world's economies into four groups, based on gross national income per capita: high, upper-middle, lower-middle, and low income countries. Least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing states are all sub-groupings of developing countries. Countries on the other end of the spectrum are usually referred to as high-income countries or developed countries.

Guns, Germs, and Steel: The Fates of Human Societies is a 1997 transdisciplinary non-fiction book by the American author Jared Diamond. The book attempts to explain why Eurasian and North African civilizations have survived and conquered others, while arguing against the idea that Eurasian hegemony is due to any form of Eurasian intellectual, moral, or inherent genetic superiority. Diamond argues that the gaps in power and technology between human societies originate primarily in environmental differences, which are amplified by various positive feedback loops. When cultural or genetic differences have favored Eurasians, he asserts that these advantages occurred because of the influence of geography on societies and cultures and were not inherent in the Eurasian genomes.

Import substitution industrialization (ISI) is a trade and economic policy that advocates replacing foreign imports with domestic production. It is based on the premise that a country should attempt to reduce its foreign dependency through the local production of industrialized products. The term primarily refers to 20th-century development economics policies, but it has been advocated since the 18th century by economists such as Friedrich List and Alexander Hamilton.

Economic geography is the subfield of human geography that studies economic activity and factors affecting it. It can also be considered a subfield or method in economics. There are four branches of economic geography.

Economic inequality is an umbrella term for:

IQ and the Wealth of Nations is a 2002 book by psychologist Richard Lynn and political scientist Tatu Vanhanen. The authors argue that differences in national income are correlated with differences in the average national intelligence quotient (IQ). They further argue that differences in average national IQs constitute one important factor, but not the only one, contributing to differences in national wealth and rates of economic growth.

Underdevelopment, in the context of international development, reflects a broad condition or phenomena defined and critiqued by theorists in fields such as economics, development studies, and postcolonial studies. Used primarily to distinguish states along benchmarks concerning human development—such as macro-economic growth, health, education, and standards of living—an "underdeveloped" state is framed as the antithesis of a "developed", modern, or industrialized state. Popularized, dominant images of underdeveloped states include those that have less stable economies, less democratic political regimes, greater poverty, malnutrition, and poorer public health and education systems.

The economy of Africa consists of the trade, industry, agriculture, and human resources of the continent. As of 2019, approximately 1.3 billion people were living in 53 countries in Africa. Africa is a resource-rich continent. Recent growth has been due to growth in sales, commodities, services, and manufacturing. West Africa, East Africa, Central Africa and Southern Africa in particular, are expected to reach a combined GDP of $29 trillion by 2050.

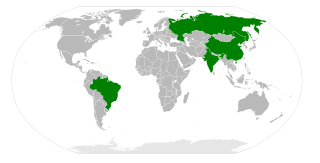

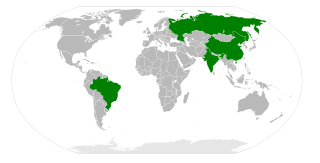

BRIC is a term describing the foreign investment strategies grouping acronym that stands for Brazil, Russia, India, and China. The separate BRICS organisation would go on to become a political and economic organization largely based on such grouping.

The resource curse, also known as the paradox of plenty or the poverty paradox, is the phenomenon of countries with an abundance of natural resources having less economic growth, less democracy, or worse development outcomes than countries with fewer natural resources. There are many theories and much academic debate about the reasons for and exceptions to the adverse outcomes. Most experts believe the resource curse is not universal or inevitable but affects certain types of countries or regions under certain conditions.

Poverty in Africa is the lack of provision to satisfy the basic human needs of certain people in Africa. African nations typically fall toward the bottom of any list measuring small size economic activity, such as income per capita or GDP per capita, despite a wealth of natural resources. In 2009, 22 of 24 nations identified as having "Low Human Development" on the United Nations' (UN) Human Development Index were in Sub-Saharan Africa. As of 2019, 424 million people in sub-Saharan Africa were reportedly living in severe poverty. In 2022, 460 million people—an increase of 36 million in only three years—were anticipated to be living in extreme poverty as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the Russo-Ukrainian war.

Development geography is a branch of geography which refers to the standard of living and its quality of life of its human inhabitants. In this context, development is a process of change that affects peoples' lives. It may involve an improvement in the quality of life as perceived by the people undergoing change. However, development is not always a positive process. Gunder Frank commented on the global economic forces that lead to the development of underdevelopment. This is covered in his dependency theory.

Poverty reduction, poverty relief, or poverty alleviation is a set of measures, both economic and humanitarian, that are intended to permanently lift people out of poverty.

International inequality refers to inequality between countries, as compared to global inequality, which is inequality between people across countries. International inequality research has primarily been concentrated on the rise of international income inequality, but other aspects include educational and health inequality, as well as differences in medical access. Reducing inequality within and among countries is the 10th goal of the UN Sustainable Development Goals and ensuring that no one is left behind is central to achieving them. Inequality can be measured by metrics such as the Gini coefficient.

African environmental issues are caused by human impacts on the natural environment and affect humans and nearly all forms of life. Issues include deforestation, soil degradation, air pollution, water pollution, garbage pollution, climate change and water scarcity. These issues result in environmental conflict and are connected to broader social struggles for democracy and sovereignty.

The Great Divergence or European miracle is the socioeconomic shift in which the Western world overcame pre-modern growth constraints and emerged during the 19th century as the most powerful and wealthy world civilizations, eclipsing previously dominant or comparable civilizations from the Middle East and Asia such as Qing China, Mughal India, the Ottoman Empire, Safavid Iran, and Tokugawa Japan, among others.

Spatial inequality refers to the unequal distribution of income and resources across geographical regions. Attributable to local differences in infrastructure, geographical features and economies of agglomeration, such inequality remains central to public policy discussions regarding economic inequality more broadly.

Climate change in Africa is an increasingly serious threat as Africa is among the most vulnerable continents to the effects of climate change. Some sources even classify Africa as "the most vulnerable continent on Earth". This vulnerability is driven by a range of factors that include weak adaptive capacity, high dependence on ecosystem goods for livelihoods, and less developed agricultural production systems. The risks of climate change on agricultural production, food security, water resources and ecosystem services will likely have increasingly severe consequences on lives and sustainable development prospects in Africa. With high confidence, it was projected by the IPCC in 2007 that in many African countries and regions, agricultural production and food security would probably be severely compromised by climate change and climate variability. Managing this risk requires an integration of mitigation and adaptation strategies in the management of ecosystem goods and services, and the agriculture production systems in Africa.

Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity, and Poverty, first published in 2012, is a book by economists Daron Acemoglu and James A. Robinson. The book applies insights from institutional economics, development economics and economic history to understand why nations develop differently, with some succeeding in the accumulation of power and prosperity and others failing, via a wide range of historical case studies.