A dictionary is a listing of lexemes from the lexicon of one or more specific languages, often arranged alphabetically, which may include information on definitions, usage, etymologies, pronunciations, translation, etc. It is a lexicographical reference that shows inter-relationships among the data.

Gibberish, also called jibber-jabber or gobbledygook, is speech that is nonsense: ranging across speech sounds that are not actual words, pseudowords, language games and specialized jargon that seems nonsensical to outsiders.

Skepticism, also spelled scepticism in British English, is a questioning attitude or doubt toward knowledge claims that are seen as mere belief or dogma. For example, if a person is skeptical about claims made by their government about an ongoing war then the person doubts that these claims are accurate. In such cases, skeptics normally recommend not disbelief but suspension of belief, i.e. maintaining a neutral attitude that neither affirms nor denies the claim. This attitude is often motivated by the impression that the available evidence is insufficient to support the claim. Formally, skepticism is a topic of interest in philosophy, particularly epistemology.

A Dictionary of the English Language, sometimes published as Johnson's Dictionary, was published on 15 April 1755 and written by Samuel Johnson. It is among the most influential dictionaries in the history of the English language.

A motto is a sentence or phrase expressing a belief or purpose, or the general motivation or intention of an individual, family, social group, or organisation. Mottos are usually found predominantly in written form, and may stem from long traditions of social foundations, or from significant events, such as a civil war or a revolution. One's motto may be in any language, but Latin has been widely used, especially in the Western world.

A scam, or confidence trick, is an attempt to defraud a person or group after first gaining their trust. Confidence tricks exploit victims using a combination of the victim's credulity, naïveté, compassion, vanity, confidence, irresponsibility, and greed. Researchers have defined confidence tricks as "a distinctive species of fraudulent conduct ... intending to further voluntary exchanges that are not mutually beneficial", as they "benefit con operators at the expense of their victims ".

Webster's Dictionary is any of the English language dictionaries edited in the early 19th century by Noah Webster (1758–1843), an American lexicographer, as well as numerous related or unrelated dictionaries that have adopted the Webster's name in his honor. "Webster's" has since become a genericized trademark in the United States for English dictionaries, and is widely used in dictionary titles.

Literal and figurative language is a distinction within some fields of language analysis, in particular stylistics, rhetoric, and semantics.

Despite the various English dialects spoken from country to country and within different regions of the same country, there are only slight regional variations in English orthography, the two most notable variations being British and American spelling. Many of the differences between American and British/Commonwealth English date back to a time before spelling standards were developed. For instance, some spellings seen as "American" today were once commonly used in Britain, and some spellings seen as "British" were once commonly used in the United States.

Naivety, naiveness, or naïveté is the state of being naive. It refers to an apparent or actual lack of experience and sophistication, often describing a neglect of pragmatism in favor of moral idealism. A naïve may be called a naïf.

Oxford spelling is a spelling standard, named after its use by the University of Oxford, that prescribes the use of British spelling in combination with the suffix -ize in words like realize and organization instead of -ise endings.

A pronunciation respelling for English is a notation used to convey the pronunciation of words in the English language, which do not have a phonemic orthography.

Hello is a salutation or greeting in the English language. It is first attested in writing from 1826.

Stupidity is a lack of intelligence, understanding, reason, or wit, an inability to learn. It may be innate, assumed or reactive. The word stupid comes from the Latin word stupere. Stupid characters are often used for comedy in fictional stories. Walter B. Pitkin called stupidity "evil", but in a more Romantic spirit William Blake and Carl Jung believed stupidity can be the mother of wisdom.

Credulity is a person's willingness or ability to believe that a statement is true, especially on minimal or uncertain evidence. Credulity is not necessarily a belief in something that may be false: the subject of the belief may even be correct, but a credulous person will believe it without good evidence.

The word ain't is a negative inflection for am, is, are, has, and have in informal English. In some dialects, it is also used for do, does, and did. The development of ain't for the various forms of be, have, and do occurred independently, at different times. The use of ain't for the forms of be was established by the mid-18th century and for the forms of have by the early 19th century.

This list comprises widespread modern beliefs about English language usage that are documented by a reliable source to be misconceptions.

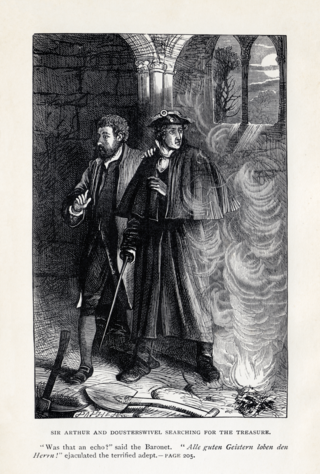

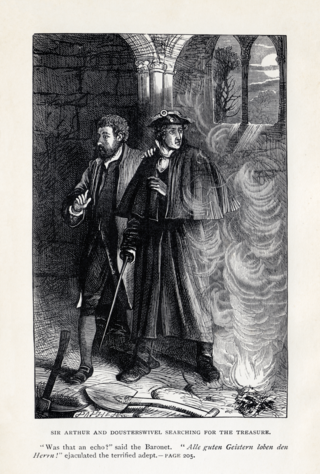

Sir Arthur Wardour of Knockwinnock Castle is a character in Walter Scott's 1816 novel The Antiquary, a Scottish Tory baronet who is vain of his ancient family but short of money. He is a friend and neighbour of Jonathan Oldbuck, the novel's title-character.

Peter Austin Nuttall was an English editor and classicist best known for dictionaries. He was born in Ormskirk, Lancashire and moved to London after completing his studies, gaining a doctorate from Aberdeen University in 1822. He was a contributor and possibly an editor of The Gentleman's Magazine between 1820 and 1837. From 1825 his editions of Latin authors were published. In 1839 he became a partner in a printing business, producing classics, educational reference books, anti-Catholic apologetics, and revised editions of older dictionaries such as Walker's and Johnson's. In 1840 he petitioned Parliament against the Copyright Bill. In 1863 Nuttall's Standard Pronouncing Dictionary of the English Language was published. Nuttall died bankrupt and was survived by five children; his wife and at least three children predeceased him. Subsequently, Frederick Warne & Co published further dictionaries under his name as late as 1973, and The Nuttall Encyclopædia in 1900.