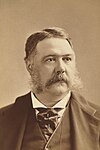

The Chinese Exclusion Act was a United States federal law signed by President Chester A. Arthur on May 6, 1882, prohibiting all immigration of Chinese laborers for 10 years. The law made exceptions for merchants, teachers, students, travelers, and diplomats. The Chinese Exclusion Act was the first major U.S. law ever implemented to prevent all members of a specific national group from immigrating to the United States, and therefore helped shape twentieth-century race-based immigration policy.

The Burlingame Treaty, also known as the Burlingame–Seward Treaty of 1868, was a landmark treaty between the United States and Qing China, amending the Treaty of Tientsin, to establish formal friendly relations between the two nations, with the United States granting China the status of most favored nation with regards to trade. It was signed in the capital of the United States, Washington, D.C. in 1868 and ratified in Peking in 1869. The most significant result of the treaty was that it effectively lifted any former restrictions in regards to emigration to the United States from China; with large-scale immigration to the United States beginning in earnest by Chinese immigrants.

The Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907 was an informal agreement between the United States of America and the Empire of Japan whereby Japan would not allow further emigration to the United States and the United States would not impose restrictions on Japanese immigrants already present in the country. The goal was to reduce tensions between the two Pacific nations such as those that followed the Pacific Coast race riots of 1907 and the segregation of Japanese students in public schools. The agreement was not a treaty and so was not voted on by the United States Congress. It was superseded by the Immigration Act of 1924.

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, also known as the Hart–Celler Act and more recently as the 1965 Immigration Act, is a landmark federal law passed by the 89th United States Congress and signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson. The law abolished the National Origins Formula, which had been the basis of U.S. immigration policy since the 1920s. The act formally removed de facto discrimination against Southern and Eastern Europeans as well as Asians, in addition to other non-Western and Northern European ethnicities from the immigration policy of the United States.

The Chinese Immigration Act, 1923, also known as the "Chinese Exclusion Act", was a Canadian Act of Parliament passed by the government of Liberal Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King, banning most forms of Chinese immigration to Canada. Immigration from most countries was controlled or restricted in some way, but only the Chinese were completely prohibited from immigrating to Canada.

The Asiatic Exclusion League was an organization formed in the early 20th century in the United States and Canada that aimed to prevent immigration of people of Asian origin.

The Immigration Act of 1917 was a United States Act that aimed to restrict immigration by imposing literacy tests on immigrants, creating new categories of inadmissible persons, and barring immigration from the Asia-Pacific zone. The most sweeping immigration act the United States had passed until that time, it followed the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 in marking a turn toward nativism. The 1917 act governed immigration policy until it was amended by the Immigration Act of 1924; both acts were revised by the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952.

Asian immigration to the United States refers to immigration to the United States from part of the continent of Asia, which includes East Asia, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. Asian-origin populations have historically been in the territory that would eventually become the United States since the 16th century. The first major wave of Asian immigration occurred in the late 19th century, primarily in Hawaii and the West Coast. Asian Americans experienced exclusion, and limitations to immigration, by the United States law between 1875 and 1965, and were largely prohibited from naturalization until the 1940s. Since the elimination of Asian exclusion laws and the reform of the immigration system in the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, there has been a large increase in the number of immigrants to the United States from Asia.

Chain migration is the social process by which immigrants from a particular area follow others from that area to a particular destination. The destination may be in another country or in a new location within the same country.

The history of Chinese Americans or the history of ethnic Chinese in the United States includes three major waves of Chinese immigration to the United States, beginning in the 19th century. Chinese immigrants in the 19th century worked in the California Gold Rush of the 1850s and the Central Pacific Railroad in the 1860s. They also worked as laborers in Western mines. They suffered racial discrimination at every level of White society. Many Americans were stirred to anger by the "Yellow Peril" rhetoric. Despite provisions for equal treatment of Chinese immigrants in the 1868 Burlingame Treaty between the U.S. and China, political and labor organizations rallied against "cheap Chinese labor".

The American Homecoming Act or Amerasian Homecoming Act, was an Act of Congress giving preferential immigration status to children in Vietnam born of U.S. fathers. The American Homecoming Act was written in 1987, passed in 1988, and implemented in 1989. The act increased Vietnamese Amerasian immigration to the U.S. because it allowed applicants to establish a mixed race identity by appearance alone. Additionally, the American Homecoming Act allowed the Amerasian children and their immediate relatives to receive refugee benefits. About 23,000 Amerasians and 67,000 of their relatives entered the United States under this act. While the American Homecoming Act was the most successful program in moving Vietnamese Amerasian children to the United States, the act was not the first attempt by the U.S. government. Additionally the act experienced flaws and controversies over the refugees it did and did not include since the act only allowed Vietnamese Amerasian children, as opposed to other South East Asian nations in which the United States also had forces in the war.

The War Brides Act was enacted on December 28, 1945, to allow alien spouses, natural children and adopted children of members of the United States Armed Forces, "if admissible", to enter the U.S. as non-quota immigrants after World War II. More than 100,000 entered the United States under this Act and its extensions and amendments until it expired in December 1948. The War Brides Act was a part of new approach to immigration law that focused on family reunification over racial exclusion. There were still racial limits that existed particularly against Asian populations, and Chinese spouses were the only Asian nationality that qualified to be brought to the United States under the act. The act was well supported and easily passed because family members of servicemen were the recipients, but concerns over marital fraud caused some tension.

John Bond Trevor Sr. (1878–1956) was an American lawyer and influential lobbyist for immigration restrictions. A wealthy nativist, he was an architect of the Immigration Act of 1924, which banned Asian immigration and established quotas that stood for forty years until 1964.

The Scott Act was a United States law that prohibited U.S. resident Chinese laborers from returning to the United States. Its main author was William Lawrence Scott of Pennsylvania, and it was signed into law by U.S. President Grover Cleveland on October 1, 1888. It was introduced to expand upon the Chinese Exclusion Act passed in 1882 and left an estimated 20,000-30,000 Chinese outside the United States at the time of its passage stranded, with no option to return to their U.S. residence.

The Pacific Coast race riots were a series of riots which occurred in the United States and Canada in 1907. The violent riots resulted from growing anti-Asian sentiment among White populations during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Rioting occurred in San Francisco, Bellingham, and Vancouver. Anti-Asian rioters in Bellingham focused mainly on several-hundred Sikh workers recently immigrated from India. Chinese immigrants were attacked in Vancouver and Japanese workers were mainly targeted in San Francisco.

The Immigration Act of 1907 was a piece of federal United States immigration legislation passed by the 59th Congress and signed into law by President Theodore Roosevelt on February 20, 1907. The Act was part of a series of reforms aimed at restricting the increasing number and groups of immigrants coming into the U.S. before World War I. The law introduced and reformed a number of restrictions on immigrants who could be admitted into the United States, most notably ones regarding disability and disease.

Chae Chan Ping v. United States, 130 U.S. 581 (1889), better known as the Chinese Exclusion Case, was a case decided by the US Supreme Court on May 13, 1889, that challenged the Scott Act of 1888, an addendum to the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

The Immigration Act of 1891, also known as the 1891 Immigration Act, was a modification of the Immigration Act of 1882, focusing on immigration rules and enforcement mechanisms for foreigners arriving from countries other than China. It was the second major federal legislation related to the mechanisms and authority of immigration enforcement, the first being the Immigration Act of 1882. The law was passed on March 3, 1891, at the end of the term of the 51st United States Congress, and signed into law by then United States President Benjamin Harrison.

Nishimura Ekiu v. United States, 142 U.S. 651 (1892), was a United States Supreme Court case challenging the constitutionality of some provisions of the Immigration Act of 1891. The case was decided against the litigant and in favor of the government, upholding the law. The case is one of two major cases that involved challenges to the Immigration Act of 1891 by Japanese immigrants, the other case being Yamataya v. Fisher.

The California Joint Immigration Committee (CJIC) was a nativist lobbying organization active in the early to mid-twentieth century that advocated exclusion of Asian and Mexican immigrants to the United States.