The Paleolithic or Palaeolithic, also called the Old Stone Age, is a period in human prehistory that is distinguished by the original development of stone tools, and which represents almost the entire period of human prehistoric technology. It extends from the earliest known use of stone tools by hominins, c. 3.3 million years ago, to the end of the Pleistocene, c. 11,650 cal BP.

The Stone Age was a broad prehistoric period during which stone was widely used to make stone tools with an edge, a point, or a percussion surface. The period lasted for roughly 3.4 million years and ended between 4,000 BC and 2,000 BC, with the advent of metalworking. Though some simple metalworking of malleable metals, particularly the use of gold and copper for purposes of ornamentation, was known in the Stone Age, it is the melting and smelting of copper that marks the end of the Stone Age. In Western Asia, this occurred by about 3,000 BC, when bronze became widespread. The term Bronze Age is used to describe the period that followed the Stone Age, as well as to describe cultures that had developed techniques and technologies for working copper alloys into tools, supplanting stone in many uses.

A stone tool is, in the most general sense, any tool made either partially or entirely out of stone. Although stone tool-dependent societies and cultures still exist today, most stone tools are associated with prehistoric cultures that have become extinct. Archaeologists often study such prehistoric societies, and refer to the study of stone tools as lithic analysis. Ethnoarchaeology has been a valuable research field in order to further the understanding and cultural implications of stone tool use and manufacture.

In archaeology, lithic analysis is the analysis of stone tools and other chipped stone artifacts using basic scientific techniques. At its most basic level, lithic analyses involve an analysis of the artifact's Morphology (archaeology), the measurement of various physical attributes, and examining other visible features.

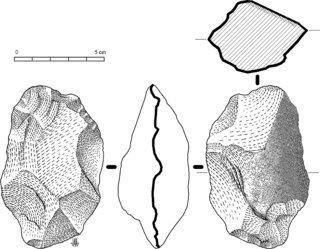

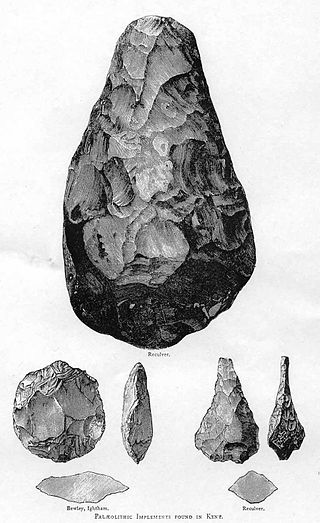

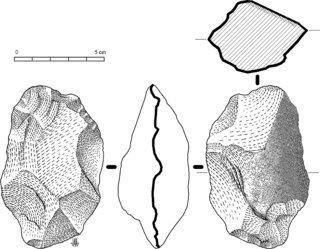

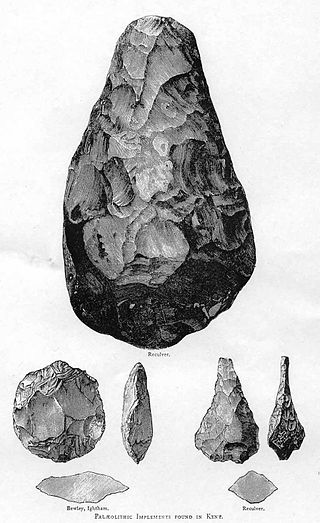

A hand axe is a prehistoric stone tool with two faces that is the longest-used tool in human history. It is made from stone, usually flint or chert that has been "reduced" and shaped from a larger piece by knapping, or hitting against another stone. They are characteristic of the lower Acheulean and middle Palaeolithic (Mousterian) periods, roughly 1.6 million years ago to about 100,000 years ago, and used by Homo erectus and other early humans, but rarely by Homo sapiens.

Acheulean, from the French acheuléen after the type site of Saint-Acheul, is an archaeological industry of stone tool manufacture characterized by the distinctive oval and pear-shaped "hand axes" associated with Homo erectus and derived species such as Homo heidelbergensis.

The Oldowan was a widespread stone tool archaeological industry (style) in prehistory. These early tools were simple, usually made with one or a few flakes chipped off with another stone. Oldowan tools were used during the Lower Paleolithic period, 2.9 million years ago up until at least 1.7 million years ago (Ma), by ancient Hominins across much of Africa. This technological industry was followed by the more sophisticated Acheulean industry.

In archaeology, a denticulate tool is a stone tool containing one or more edges that are worked into multiple notched shapes, much like the toothed edge of a saw. Such tools have been used as saws for woodworking, processing meat and hides, craft activities and for agricultural purposes. Denticulate tools were used by many different groups worldwide and have been found at a number of notable archaeological sites. They can be made from a number of different lithic materials, but a large number of denticulate tools are made from flint.

The Châtelperronian is a proposed industry of the Upper Palaeolithic, the existence of which is debated. It represents both the only Upper Palaeolithic industry made by Neanderthals and the earliest Upper Palaeolithic industry in central and southwestern France, as well as in northern Spain. It derives its name from Châtelperron, the French village closest to the type site, the cave La Grotte des Fées.

Abbevillian is a term for the oldest lithic industry found in Europe, dated to between roughly 600,000 and 400,000 years ago.

The Lower Paleolithic is the earliest subdivision of the Paleolithic or Old Stone Age. It spans the time from around 3.3 million years ago when the first evidence for stone tool production and use by hominins appears in the current archaeological record, until around 300,000 years ago, spanning the Oldowan and Acheulean lithics industries.

The Levallois technique is a name given by archaeologists to a distinctive type of stone knapping developed around 250,000 to 300,000 years ago during the Middle Palaeolithic period. It is part of the Mousterian stone tool industry, and was used by the Neanderthals in Europe and by modern humans in other regions such as the Levant.

Archaeologists define a chopper as a pebble tool with an irregular cutting edge formed through the removal of flakes from one side of a stone.

In archaeology, a cleaver is a type of biface stone tool of the Lower Palaeolithic.

The Chelleo-Acheulean is a Palaeolithic stone tool industry that marks a transitional stage between the Chellean and the Acheulean. Louis Leakey identified eleven stages of development in the Chelleo-Acheulean "hand axe culture" in Africa.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to prehistoric technology.

Kariandusi prehistoric site is an archaeological site in Kenya. Located on the southeastern edge of the Great Rift Valley and on Lake Elmenteita, Kariandusi is an African Early Stone Age site dating to approximately 1 million years ago.

Gona is a paleoanthropological research area in Ethiopia's Afar Region. Gona is primarily known for its archaeological sites and discoveries of hominin fossils from the Late Miocene, Early Pliocene and Early Pleistocene. Fossils of Ardipithecus and Homo erectus were discovered there. Two of the most significant finds are an Ardipithecus ramidus postcranial skeleton and an essentially complete Homo erectus pelvis. Historically, Gona had the oldest documented Oldowan artifact assemblages. Archaeologists have since found older examples of the Oldowan at other sites. Still, Gona's Oldowan assemblages have been essential to the archaeological understanding of the Oldowan. Gona's Acheulean archaeological sites have helped us understand the beginnings of the Acheulean Industry.

Chesowanja is a Kenian archaeological site located in the north of the Kenya Rift Valley, east of Lake Baringo. The Chesowanja sites consist of quaternary sediments. The sites are home to various discoveries like fossils, evidence of human activity over a period of 2 million years and the remains of Australopithecus. Also, artefacts belonging to Oldowan technology, Acheulean tradition and later stone industries have been found.