Franco Modigliani was an Italian-American economist and the recipient of the 1985 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economics. He was a professor at University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign, Carnegie Mellon University, and MIT Sloan School of Management.

Saving is income not spent, or deferred consumption. Methods of saving include putting money aside in, for example, a deposit account, a pension account, an investment fund, or as cash. Saving also involves reducing expenditures, such as recurring costs. In terms of personal finance, saving generally specifies low-risk preservation of money, as in a deposit account, versus investment, wherein risk is a lot higher; in economics more broadly, it refers to any income not used for immediate consumption. Saving does not automatically include interest.

This aims to be a complete article list of economics topics:

Intertemporal choice is the process by which people make decisions about what and how much to do at various points in time, when choices at one time influence the possibilities available at other points in time. These choices are influenced by the relative value people assign to two or more payoffs at different points in time. Most choices require decision-makers to trade off costs and benefits at different points in time. These decisions may be about saving, work effort, education, nutrition, exercise, health care and so forth. Greater preference for immediate smaller rewards has been associated with many negative outcomes ranging from lower salary to drug addiction.

In economics, time preference is the current relative valuation placed on receiving a good or some cash at an earlier date compared with receiving it at a later date.

The marginal propensity to save (MPS) is the fraction of an increase in income that is not spent and instead used for saving. It is the slope of the line plotting saving against income. For example, if a household earns one extra dollar, and the marginal propensity to save is 0.35, then of that dollar, the household will spend 65 cents and save 35 cents. Likewise, it is the fractional decrease in saving that results from a decrease in income.

Consumption is the act of using resources to satisfy current needs and wants. It is seen in contrast to investing, which is spending for acquisition of future income. Consumption is a major concept in economics and is also studied in many other social sciences.

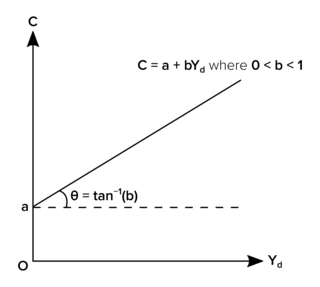

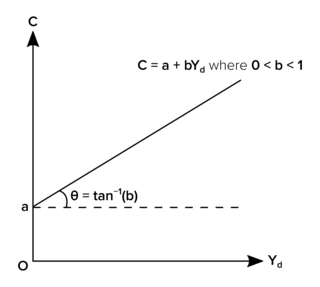

In economics, the marginal propensity to consume (MPC) is a metric that quantifies induced consumption, the concept that the increase in personal consumer spending (consumption) occurs with an increase in disposable income. The proportion of disposable income which individuals spend on consumption is known as propensity to consume. MPC is the proportion of additional income that an individual consumes. For example, if a household earns one extra dollar of disposable income, and the marginal propensity to consume is 0.65, then of that dollar, the household will spend 65 cents and save 35 cents. Obviously, the household cannot spend more than the extra dollar. The MPC is higher in the case of poorer people than in rich.

In economics, the consumption function describes a relationship between consumption and disposable income. The concept is believed to have been introduced into macroeconomics by John Maynard Keynes in 1936, who used it to develop the notion of a government spending multiplier.

The overlapping generations (OLG) model is one of the dominating frameworks of analysis in the study of macroeconomic dynamics and economic growth. In contrast, to the Ramsey–Cass–Koopmans neoclassical growth model in which individuals are infinitely-lived, in the OLG model individuals live a finite length of time, long enough to overlap with at least one period of another agent's life.

The wealth elasticity of demand, in microeconomics and macroeconomics, is the proportional change in the consumption of a good relative to a change in consumers' wealth. Measuring and accounting for the variability in this elasticity is a continuing problem in behavioral finance and consumer theory.

Average propensity to consume (as well as the marginal propensity to consume) is a concept developed by John Maynard Keynes to analyze the consumption function, which is a formula where total consumption expenditures (C) of a household consist of autonomous consumption (Ca) and income (Y) multiplied by marginal propensity to consume. According to Keynes, the individual´s real income determines saving and consumption decisions.

In economics, the life-cycle hypothesis (LCH) is a model that strives to explain the consumption patterns of individuals.

The permanent income hypothesis (PIH) is a model in the field of economics to explain the formation of consumption patterns. It suggests consumption patterns are formed from future expectations and consumption smoothing. The theory was developed by Milton Friedman and published in his A Theory of Consumption Function, published in 1957 and subsequently formalized by Robert Hall in a rational expectations model. Originally applied to consumption and income, the process of future expectations is thought to influence other phenomena. In its simplest form, the hypothesis states changes in permanent income, rather than changes in temporary income, are what drive changes in consumption.

Dissaving is negative saving. If spending is greater than disposable income, dissaving is taking place. This spending is financed by already accumulated savings, such as money in a savings account, or it can be borrowed. Household dissaving therefore corresponds to an absolute decrease in their financial investments.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to finance:

Consumption smoothing is the economic concept used to express the desire of people to have a stable path of consumption. People desire to translate their consumption from periods of high income to periods of low income to obtain more stability and predictability. There exist many states of the world, which means there are many possible outcomes that can occur throughout an individual's life. Therefore, to reduce the uncertainty that occurs, people choose to give up some consumption today to prevent against an adverse outcome in the future. In order for one to adequately and properly prepare for unforeseen circumstances that can occur in the future, we must start planning today, putting money aside for when these unforeseen circumstances happen.

Elasticity of intertemporal substitution is a measure of responsiveness of the growth rate of consumption to the real interest rate. If the real interest rate rises, current consumption may decrease due to increased return on savings; but current consumption may also increase as the household decides to consume more immediately, as it is feeling richer. The net effect on current consumption is the elasticity of intertemporal substitution.

The random walk model of consumption was introduced by economist Robert Hall. This model uses the Euler numerical method to model consumption. He created his consumption theory in response to the Lucas critique. Using Euler equations to model the random walk of consumption has become the dominant approach to modeling consumption.

Precautionary saving is saving that occurs in response to uncertainty regarding future income. The precautionary motive to delay consumption and save in the current period rises due to the lack of completeness of insurance markets. Accordingly, individuals will not be able to insure against some bad state of the economy in the future. They anticipate that if this bad state is realized, they will earn lower income. To avoid adverse effects of future income fluctuations and retain a smooth path of consumption, they set aside a precautionary reserve, called precautionary savings, by consuming less in the current period, and resort to it in case the bad state is realized in the future.