Related Research Articles

Burmese is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Myanmar, where it is the official language, lingua franca, and the native language of the Bamar, the country's principal ethnic group. Burmese is also spoken by the indigenous tribes in Chittagong Hill Tracts in Bangladesh, and in Tripura state in India. The Constitution of Myanmar officially refers to it as the Myanmar language in English, though most English speakers continue to refer to the language as Burmese, after Burma—a name with co-official status that had historically been predominantly used for the country. Burmese is the most widely-spoken language in the country, where it serves as the lingua franca. In 2007, it was spoken as a first language by 33 million. Burmese is spoken as a second language by another 10 million people, including ethnic minorities in Myanmar like the Mon and also by those in neighboring countries. In 2022, the Burmese-speaking population was 38.8 million.

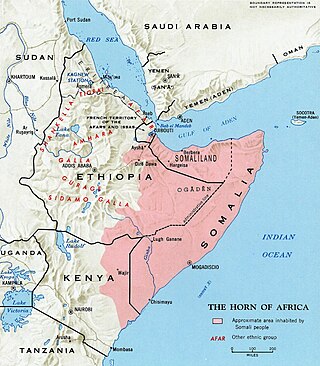

Somali is an Afroasiatic language belonging to the Cushitic branch. It is spoken as a mother tongue by Somalis in Greater Somalia and the Somali diaspora. Somali is an official language in Somalia and Ethiopia, and a national language in Djibouti as well as in northeastern Kenya. The Somali language is written officially with the Latin alphabet although the Arabic alphabet and several Somali scripts like Osmanya, Kaddare and the Borama script are informally used.

The Shan language is the native language of the Shan people and is mostly spoken in Shan State, Myanmar. It is also spoken in pockets in other parts of Myanmar, in Northern Thailand, in Yunnan, in Laos, in Cambodia, in Vietnam and decreasingly in Assam and Meghalaya. Shan is a member of the Tai–Kadai language family and is related to Thai. It has five tones, which do not correspond exactly to Thai tones, plus a sixth tone used for emphasis. The term Shan is also used for related Northwestern Tai languages, and it is called Tai Yai or Tai Long in other Tai languages. Standard Shan, which is also known as Tachileik Shan, is based on the dialect of the city of Tachileik.

Lisu is a tonal Tibeto-Burman language spoken in Yunnan, Northern Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand and a small part of India. Along with Lipo, it is one of two languages of the Lisu people. Lisu has many dialects that originate from the country in which they live. Hua Lisu, Pai Lisu and Lu Shi Lisu dialects are spoken in China. Although they are mutually intelligible, some have many more loan words from other languages than others.

Tai Lue or Xishuangbanna Dai is a Tai language of the Lu people, spoken by about 700,000 people in Southeast Asia. This includes 280,000 people in China (Yunnan), 200,000 in Burma, 134,000 in Laos, 83,000 in Thailand and 4,960 in Vietnam. The language is similar to other Tai languages and is closely related to Kham Mueang or Tai Yuan, which is also known as Northern Thai language. In Yunnan, it is spoken in all of Xishuangbanna Dai Autonomous Prefecture, as well as Jiangcheng Hani and Yi Autonomous County in Pu'er City.

The Khamti language is a Southwestern Tai language spoken in Myanmar and India by the Khamti people. It is closely related to, and sometimes considered a dialect of, Shan.

There are approximately a hundred languages spoken in Myanmar. Burmese, spoken by two-thirds of the population, is the official language.

Mangareva, Mangarevan is a Polynesian language spoken by about 600 people in the Gambier Islands of French Polynesia and by Mangarevians emigrants on the islands of Tahiti and Moorea, located 1,650 kilometres (1,030 mi) to the North-West of the Gambier Islands.

Jingpo or Kachin is a Tibeto-Burman language of the Sal branch spoken primarily in Kachin State, Myanmar; Northeast India; and Yunnan, China. The Jingpo peoples, a confederation of several ethnic groups who live in the Kachin Hills, are the primary speakers of Jingpo language, numbering approximately 1,000,000 speakers. The term "Kachin language" may refer to the Jingpo language or any of the other languages spoken by the Jingpo peoples, such as Lisu, Lashi, Rawang, Zaiwa, Lhao Vo, and Achang. These languages are from distinct branches of the highest level of the Tibeto-Burman family.

S’gaw, S'gaw Karen, or S’gaw K’Nyaw, commonly known as Karen, is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the S'gaw Karen people of Myanmar and Thailand. A Karenic branch of the Sino-Tibetan language family, S'gaw Karen is spoken by over 2 million people in Tanintharyi Region, Ayeyarwady Region, Yangon Region, and Bago Region in Myanmar, and about 200,000 in northern and western Thailand along the border near Kayin State. It is written using the S'gaw Karen alphabet, derived from the Burmese script, although a Latin-based script is also in use among the S'gaw Karen in northwestern Thailand.

Southern Anung is a Sino-Tibetan language spoken by the Nung people in Fugong County, China, and Kachin State, Myanmar. The Anung language is closely related to the Derung and Rawang languages. Most of the Anung speakers in China have shifted to Lisu, although the speakers are classified as Nu people. The Northern Anung people speak a dialect of Derung, which is also called Anung, but is not the same Anung discussed in this article.

Tangsa, also known as Tase and Tase Naga, is a Sino-Tibetan language or language cluster spoken by the Tangsa people of Burma and north-eastern India. Some varieties, such as Shangge (Shanke), are likely distinct languages. There are about 60,000 speakers in Burma and 40,000 speakers in India. The dialects of Tangsa have disparate levels of lexical similarity, ranging from 35%–97%.

Eastern Pwo or Phlou, is a Karen language spoken by Eastern Pwo people and over a million people in Myanmar and by about 50,000 in Thailand, where it has been called Southern Pwo. It is not intelligible with other varieties of Pwo, with which it shares 63 to 65% lexical similarity. The Eastern Pwo dialects share 91 to 97% lexical similarity.

Mok, also known as Amok, Hsen-Hsum, and Muak, is an Angkuic language or dialect cluster spoken in Shan State, Myanmar

Tai Loi, also known as Mong Lue, refers to various Palaungic languages spoken mainly in Burma, with a few hundred in Laos and some also in China. Hall (2017) reports that Tai Loi is a cover term meaning 'mountain Tai' in Shan, and refers to various Angkuic, Waic, and Western Palaungic languages rather than a single language or branch. The Shan exonym Tai Loi can refer to:

Pyen is a Loloish language of Myanmar. It is spoken by about 700 people in two villages near Mong Yang, Shan State, Burma, just to the north of Kengtung.

Southern Alta, is a distinctive Aeta language of the mountains of northern Philippines. Southern Alta is one of many endangered languages that risks being lost if it is not passed on by current speakers. Most speakers of Southern Alta also speak Tagalog.

Rakhine, also known as Arakanese, is a Tibeto-Burman language spoken in western Myanmar, primarily in the Rakhine State. Closely related to Burmese, the language is spoken by the Rakhine and Marma peoples; it is estimated to have around one million native speakers and it is spoken as a second language by a further million.

The Taungyo are a sub-ethnic group of the Bamar people living primarily in Shan State and centered on Pindaya.

The Shan alphabet is a Brahmic abugida, used for writing the Shan language, which was derived from the Burmese alphabet. Due to its recent reforms, the Shan alphabet is more phonetic than other Burmese-derived alphabets.

References

- 1 2 Danu at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

Intha at Ethnologue (21st ed., 2018)

- ↑ "Myanmar - Languages" (PDF). Ethnologue. 2016-07-24.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Salem-Gervais, Nicolas; Raynaud, Mael (2020). Teaching ethnic minority languages in government schools and developing the local curriculum: Elements of decentralization in language-in-education policy (PDF). Yangon: Konrad-Adenauer Stiftung. pp. 144–146. ISBN 978-99971-0-558-5.

- ↑ Barron, Sandy; John Okell; Saw Myat Yin; Kenneth VanBik; Arthur Swain; Emma Larkin; Anna J. Allott; Kirsten Ewers (2007). Refugees From Burma: Their Backgrounds and Refugee Experiences (PDF) (Report). Center for Applied Linguistics. pp. 16–17. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-04-27. Retrieved 2010-08-20.

- 1 2 ခင်စန္ဒာတိုး (2018). "နောင်ချိုဒေသရှိ ဓနုဒေသိယစကားမှ နေ့စဉ်သုံးစကားများလေ့လာချက်" (PDF). Journal of the Myanmar Academy of Arts and Science (in Burmese). XVI (6B).

- ↑ Elder sister's husband, or husband's elder brother

- 1 2 "Teaching Ethnic Languages, Cultures and Histories in Government Schools today: Great Opportunities, Giant Pitfalls? (Part II)". Tea Circle. 2018-10-02. Retrieved 2023-04-01.