Related Research Articles

Mania, also known as manic syndrome, is a mental and behavioral disorder defined as a state of abnormally elevated arousal, affect, and energy level, or "a state of heightened overall activation with enhanced affective expression together with lability of affect." During a manic episode, an individual will experience rapidly changing emotions and moods, highly influenced by surrounding stimuli. Although mania is often conceived as a "mirror image" to depression, the heightened mood can be either euphoric or dysphoric. As the mania intensifies, irritability can be more pronounced and result in anxiety or anger.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD), also known as emotionally unstable personality disorder (EUPD), is a personality disorder characterized by a pervasive, long-term pattern of significant interpersonal relationship instability, a distorted sense of self, and intense emotional responses. Individuals diagnosed with BPD frequently exhibit self-harming behaviours and engage in risky activities, primarily due to challenges in regulating emotional states to a healthy, stable baseline. Symptoms such as dissociation, a pervasive sense of emptiness, and an acute fear of abandonment are prevalent among those affected.

A mood swing is an extreme or sudden change of mood. Such changes can play a positive part in promoting problem solving and in producing flexible forward planning, or be disruptive. When mood swings are severe, they may be categorized as part of a mental illness, such as bipolar disorder, where erratic and disruptive mood swings are a defining feature.

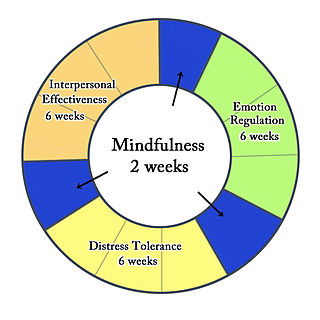

Dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) is an evidence-based psychotherapy that began with efforts to treat personality disorders and interpersonal conflicts. Evidence suggests that DBT can be useful in treating mood disorders and suicidal ideation as well as for changing behavioral patterns such as self-harm and substance use. DBT evolved into a process in which the therapist and client work with acceptance and change-oriented strategies and ultimately balance and synthesize them—comparable to the philosophical dialectical process of thesis and antithesis, followed by synthesis.

Cognitive disengagement syndrome (CDS) is an attention syndrome characterised by prominent dreaminess, mental fogginess, hypoactivity, sluggishness, slow reaction time, staring frequently, inconsistent alertness, and a slow working speed. To scientists in the field, it has reached the threshold of evidence and recognition as a distinct syndrome.

In medicine and psychology, emotional lability is a sign or symptom typified by exaggerated changes in mood or affect in quick succession. Sometimes the emotions expressed outwardly are very different from how the person feels on the inside. These strong emotions can be a disproportionate response to something that happened, but other times there might be no trigger at all. The person experiencing emotional lability usually feels like they do not have control over their emotions. For example, someone might cry uncontrollably in response to any strong emotion even if they do not feel sad or unhappy.

Suicidal ideation, or suicidal thoughts, is the thought process of having ideas, or ruminations about the possibility of completing suicide. It is not a diagnosis but is a symptom of some mental disorders, use of certain psychoactive drugs, and can also occur in response to adverse life events without the presence of a mental disorder.

Emotional dysregulation is characterized by an inability in flexibly responding to and managing emotional states, resulting in intense and prolonged emotional reactions that deviate from social norms, given the nature of the environmental stimuli encountered. Such reactions not only deviate from accepted social norms but also surpass what is informally deemed appropriate or proportional to the encountered stimuli.

Hysteroid dysphoria is a name given to repeated episodes of depressed mood in response to feeling rejected.

Bipolar disorder in children, or pediatric bipolar disorder (PBD), is a rare mental disorder in children and adolescents. The diagnosis of bipolar disorder in children has been heavily debated for many reasons including the potential harmful effects of adult bipolar medication use for children. PBD is similar to bipolar disorder (BD) in adults, and has been proposed as an explanation for periods of extreme shifts in mood called mood episodes. These shifts alternate between periods of depressed or irritable moods and periods of abnormally elevated moods called manic or hypomanic episodes. Mixed mood episodes can occur when a child or adolescent with PBD experiences depressive and manic symptoms simultaneously. Mood episodes of children and adolescents with PBD are different from general shifts in mood experienced by children and adolescents because mood episodes last for long periods of time and cause severe disruptions to an individual's life. There are three known forms of PBD: Bipolar I, Bipolar II, and Bipolar Not Otherwise Specified (NOS). The average age of onset of PBD remains unclear, but reported age of onset ranges from 5 years of age to 19 years of age. PBD is typically more severe and has a poorer prognosis than bipolar disorder with onset in late-adolescence or adulthood.

Bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (BD-NOS) is a diagnosis for bipolar disorder (BD) when it does not fall within the other established sub-types. Bipolar disorder NOS is sometimes referred to as subthreshold bipolar disorder.

The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia (SADS) is a collection of psychiatric diagnostic criteria and symptom rating scales originally published in 1978. It is organized as a semi-structured diagnostic interview. The structured aspect is that every interview asks screening questions about the same set of disorders regardless of the presenting problem; and positive screens get explored with a consistent set of symptoms. These features increase the sensitivity of the interview and the inter-rater reliability of the resulting diagnoses. The SADS also allows more flexibility than fully structured interviews: Interviewers can use their own words and rephrase questions, and some clinical judgment is used to score responses. There are three versions of the schedule, the regular SADS, the lifetime version (SADS-L) and a version for measuring the change in symptomology (SADS-C). Although largely replaced by more structured interviews that follow diagnostic criteria such as DSM-IV and DSM-5, and specific mood rating scales, versions of the SADS are still used in some research papers today.

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a mental disorder in children and adolescents characterized by a persistently irritable or angry mood and frequent temper outbursts that are disproportionate to the situation and significantly more severe than the typical reaction of same-aged peers. DMDD was added to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-V) as a type of depressive disorder diagnosis for youths. The symptoms of DMDD resemble many other disorders, thus a differential includes attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), oppositional defiant disorder (ODD), anxiety disorders, and childhood bipolar disorder, intermittent explosive disorder (IED), major depressive disorder (MDD), and conduct disorder.

Sex and gender differences in autism exist regarding prevalence, presentation, and diagnosis.

Emotions play a key role in overall mental health, and sleep plays a crucial role in maintaining the optimal homeostasis of emotional functioning. Deficient sleep, both in the form of sleep deprivation and restriction, adversely impacts emotion generation, emotion regulation, and emotional expression.

Kathleen Ries Merikangas is the Chief of the Genetic Epidemiology Research Branch in the Intramural Research Program at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) and an adjunct professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. She has published more than 300 papers, and is best known for her work in adolescent mental disorders.

Connie Kasari is an expert on autism spectrum disorder and a founding member of the Center for Autism Research and Treatment (CART) at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA). Kasari is Professor of Psychological Studies in Education at UCLA and Professor of Psychiatry at the David Geffen School of Medicine at UCLA. She is the leader of the Autism Intervention Research Network for Behavioral Health, a nine-institution research consortium.

Youth suicide in India is when young Indian people deliberately end their own life. People aged 15 to 24 years have the highest suicide rate in India, which is consistent with international trends in youth suicide. 35% of recorded suicides in India occur in this age group. Risk factors and methods of youth suicide differ from those in other age groups.

Ellen Leibenluft is an American psychiatrist and physician-scientist researching the brain mechanisms mediating bipolar disorder and severe irritability in children and adolescents. She is a senior investigator and chief of the mood dysregulation and neuroscience section at the National Institute of Mental Health.

The Early Start Denver Model (ESDM) is a form of intervention directed at young children that display early signs of being on the autism spectrum proposed by American psychiatrists Sally J. Rogers and Geraldine Dawson. It is intended to help children improve development traits as early as possible so as to narrow or close the gaps in capabilities between the individual and their peers.

References

- 1 2 D, Venes (2013). Taber's Cyclopedic Medical Dictionary. Philadelphia, Pennsylvania: F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-2977-6.

- 1 2 Vidal-Ribas, Pablo; Brotman, Melissa A.; Valdivieso, Isabel; Leibenluft, Ellen; Stringaris, Argyris (2016). "The Status of Irritability in Psychiatry: A Conceptual and Quantitative Review". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 55 (7): 556–570. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2016.04.014. ISSN 0890-8567. PMC 4927461 . PMID 27343883.

- ↑ Eshel, Neir; Leibenluft, Ellen (2019-12-04). "New Frontiers in Irritability Research—From Cradle to Grave and Bench to Bedside". JAMA Psychiatry. 77 (3): 227–228. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3686. PMID 31799997. S2CID 208621875.

- ↑ Caprara, G.V.; Cinanni, V.; D'Imperio, G.; Passerini, S.; Renzi, P.; Travaglia, G. (1985). "Indicators of impulsive aggression: Present status of research on irritability and emotional susceptibility scales". Personality and Individual Differences. 6 (6): 665–674. doi:10.1016/0191-8869(85)90077-7. ISSN 0191-8869.

- ↑ Holtzman, Susan; O'Connor, Brian P.; Barata, Paula C.; Stewart, Donna E. (2014-05-15). "The Brief Irritability Test (BITe)". Assessment. 22 (1): 101–115. doi:10.1177/1073191114533814. ISSN 1073-1911. PMC 4318695 . PMID 24830513.

- 1 2 3 Toohey, Michael J.; DiGiuseppe, Raymond (April 2017). "Defining and measuring irritability: Construct clarification and differentiation". Clinical Psychology Review. 53: 93–108. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2017.01.009. PMID 28284170.

- ↑ Beauchaine, Theodore P.; Tackett, Jennifer L. (2020). "Irritability as a Transdiagnostic Vulnerability Trait:Current Issues and Future Directions". Behavior Therapy. 51 (2): 350–364. doi:10.1016/j.beth.2019.10.009. ISSN 0005-7894. PMID 32138943. S2CID 212565146.

- ↑ Bettencourt, B. Ann; Talley, Amelia; Benjamin, Arlin James; Valentine, Jeffrey (2006). "Personality and aggressive behavior under provoking and neutral conditions: A meta-analytic review". Psychological Bulletin. 132 (5): 751–777. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.751. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 16910753. S2CID 10793794.

- ↑ Malhi, Gin; Bell, Erica; Outhred, Tim (2019-06-27). "Getting irritable about irritability?". Evidence-Based Mental Health. 22 (3): 93–94. doi:10.1136/ebmental-2019-300101. ISSN 1362-0347. PMC 10270366 . PMID 31248977.

- ↑ Berkowitz, Leonard (1989). "Frustration-aggression hypothesis: Examination and reformulation". Psychological Bulletin. 106 (1): 59–73. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.106.1.59. ISSN 1939-1455. PMID 2667009.

- ↑ "NIMH " Construct: Frustrative Nonreward". www.nimh.nih.gov. Retrieved 2020-04-10.

- ↑ Kaat, Aaron J.; Lecavalier, Luc; Aman, Michael G. (2013-10-29). "Validity of the Aberrant Behavior Checklist in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorder". Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. 44 (5): 1103–1116. doi:10.1007/s10803-013-1970-0. ISSN 0162-3257. PMID 24165702. S2CID 254571975.

- 1 2 Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders : DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association., American Psychiatric Association. DSM-5 Task Force. (5th ed.). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association. 2013. ISBN 978-0-89042-554-1. OCLC 830807378.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Stringaris, Argyris (5 March 2015). Disruptive mood : irritability in children and adolescents. Taylor, Eric. Oxford. ISBN 978-0-19-166205-8. OCLC 905544004.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Towbin, Kenneth; Axelson, David; Leibenluft, Ellen; Birmaher, Boris (2013). "Differentiating Bipolar Disorder–Not Otherwise Specified and Severe Mood Dysregulation". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 52 (5): 466–481. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.02.006. ISSN 0890-8567. PMC 3697010 . PMID 23622848.

- ↑ Wiggins, Jillian Lee; Mitchell, Colter; Stringaris, Argyris; Leibenluft, Ellen (2014). "Developmental Trajectories of Irritability and Bidirectional Associations With Maternal Depression". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 53 (11): 1191–1205.e4. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2014.08.005. ISSN 0890-8567. PMC 4254549 . PMID 25440309.

- ↑ Pickles, A.; Aglan, A.; Collishaw, S.; Messer, J.; Rutter, M.; Maughan, B. (2009-11-26). "Predictors of suicidality across the life span: The Isle of Wight study" (PDF). Psychological Medicine. 40 (9): 1453–1466. doi:10.1017/s0033291709991905. ISSN 0033-2917. PMID 19939326. S2CID 8465693.

- ↑ Conner, Kenneth R.; Meldrum, Sean; Wieczorek, William F.; Duberstein, Paul R.; Welte, John W. (2004). "The Association of Irritability and Impulsivity with Suicidal Ideation Among 15- to 20-year-old Males". Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior. 34 (4): 363–373. doi:10.1521/suli.34.4.363.53745. ISSN 0363-0234. PMID 15585458.

- ↑ Brezo, J.; Paris, J.; Turecki, G. (2006). "Personality traits as correlates of suicidal ideation, suicide attempts, and suicide completions: a systematic review". Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 113 (3): 180–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2005.00702.x . ISSN 0001-690X. PMID 16466403. S2CID 12219596.

- ↑ Brotman, Melissa A.; Kircanski, Katharina; Stringaris, Argyris; Pine, Daniel S.; Leibenluft, Ellen (2017). "Irritability in Youths: A Translational Model". American Journal of Psychiatry. 174 (6): 520–532. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2016.16070839 . ISSN 0002-953X. PMID 28103715.