A ventilator is a type of breathing apparatus, a class of medical technology that provides mechanical ventilation by moving breathable air into and out of the lungs, to deliver breaths to a patient who is physically unable to breathe, or breathing insufficiently. Ventilators may be computerized microprocessor-controlled machines, but patients can also be ventilated with a simple, hand-operated bag valve mask. Ventilators are chiefly used in intensive-care medicine, home care, and emergency medicine and in anesthesiology.

Mechanical ventilation or assisted ventilation is the medical term for using a machine called a ventilator to fully or partially provide artificial ventilation. Mechanical ventilation helps move air into and out of the lungs, with the main goal of helping the delivery of oxygen and removal of carbon dioxide. Mechanical ventilation is used for many reasons, including to protect the airway due to mechanical or neurologic cause, to ensure adequate oxygenation, or to remove excess carbon dioxide from the lungs. Various healthcare providers are involved with the use of mechanical ventilation and people who require ventilators are typically monitored in an intensive care unit.

Intensive care medicine, also called critical care medicine, is a medical specialty that deals with seriously or critically ill patients who have, are at risk of, or are recovering from conditions that may be life-threatening. It includes providing life support, invasive monitoring techniques, resuscitation, and end-of-life care. Doctors in this specialty are often called intensive care physicians, critical care physicians, or intensivists.

A hospital-acquired infection, also known as a nosocomial infection, is an infection that is acquired in a hospital or other healthcare facility. To emphasize both hospital and nonhospital settings, it is sometimes instead called a healthcare-associated infection. Such an infection can be acquired in a hospital, nursing home, rehabilitation facility, outpatient clinic, diagnostic laboratory or other clinical settings. A number of dynamic processes can bring contamination into operating rooms and other areas within nosocomial settings. Infection is spread to the susceptible patient in the clinical setting by various means. Healthcare staff also spread infection, in addition to contaminated equipment, bed linens, or air droplets. The infection can originate from the outside environment, another infected patient, staff that may be infected, or in some cases, the source of the infection cannot be determined. In some cases the microorganism originates from the patient's own skin microbiota, becoming opportunistic after surgery or other procedures that compromise the protective skin barrier. Though the patient may have contracted the infection from their own skin, the infection is still considered nosocomial since it develops in the health care setting. Nosocomial infection tends to lack evidence that it was present when the patient entered the healthcare setting, thus meaning it was acquired post-admission.

Artificial ventilation or respiration is when a machine assists in a metabolic process to exchange gases in the body by pulmonary ventilation, external respiration, and internal respiration. A machine called ventilator provides the person air manually by moving air in and out of the lungs when an individual is unable to breathe on their own. The ventilator prevents the accumulation of carbon dioxide so that the lungs don't collapse due to the low pressure. The use of artificial ventilation can be traced back to the seventeenth century. There are three ways of exchanging gases in the body: manual methods, mechanical ventilation, and neurostimulation.

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a type of lung infection that occurs in people who are on mechanical ventilation breathing machines in hospitals. As such, VAP typically affects critically ill persons that are in an intensive care unit (ICU) and have been on a mechanical ventilator for at least 48 hours. VAP is a major source of increased illness and death. Persons with VAP have increased lengths of ICU hospitalization and have up to a 20–30% death rate. The diagnosis of VAP varies among hospitals and providers but usually requires a new infiltrate on chest x-ray plus two or more other factors. These factors include temperatures of >38 °C or <36 °C, a white blood cell count of >12 × 109/ml, purulent secretions from the airways in the lung, and/or reduction in gas exchange.

Hill-Rom Holdings, Inc., doing business as Hillrom, is an American medical technology provider that is a subsidiary of Baxter International.

An intensive care unit (ICU), also known as an intensive therapy unit or intensive treatment unit (ITU) or critical care unit (CCU), is a special department of a hospital or health care facility that provides intensive care medicine.

The Surviving Sepsis Campaign (SSC) is a global initiative to bring together professional organizations in reducing mortality from sepsis. The purpose of the SSC is to create an international collaborative effort to improve the treatment of sepsis and reduce the high mortality rate associated with the condition. The Surviving Sepsis Campaign and the Institute for Healthcare Improvement have teamed up to achieve a 25 percent reduction in sepsis mortality by 2009. The guidelines were updated in 2016 and again in 2021.

Geriatric intensive care unit is a special intensive care unit dedicated to management of critically ill elderly.

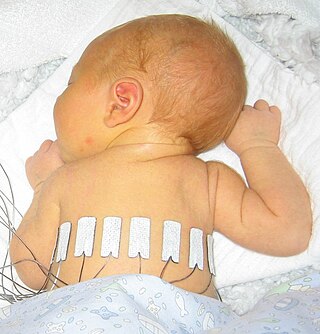

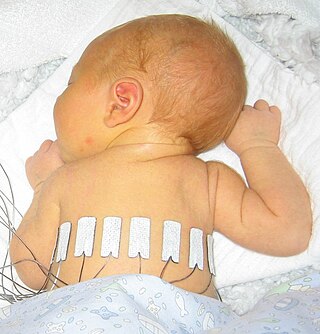

Prone ventilation, sometimes called prone positioning or proning, is a method of mechanical ventilation with the patient lying face-down (prone). It improves oxygenation in most patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) and reduces mortality. The earliest trial investigating the benefits of prone ventilation occurred in 1976. Since that time, many meta-analyses and one randomized control trial, the PROSEVA trial, have shown an increase in patients' survival with the more severe versions of ARDS. There are many proposed mechanisms, but they are not fully delineated. The proposed utility of prone ventilation is that this position will improve lung mechanics, improve oxygenation, and increase survival. Although improved oxygenation has been shown in multiple studies, this position change's survival benefit is not as clear. Similar to the slow adoption of low tidal volume ventilation utilized in ARDS, many believe that the investigation into the benefits of prone ventilation will likely be ongoing in the future.

Flattening the curve is a public health strategy to slow down the spread of an epidemic, used against the SARS-CoV-2 virus during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. The curve being flattened is the epidemic curve, a visual representation of the number of infected people needing health care over time. During an epidemic, a health care system can break down when the number of people infected exceeds the capability of the health care system's ability to take care of them. Flattening the curve means slowing the spread of the epidemic so that the peak number of people requiring care at a time is reduced, and the health care system does not exceed its capacity. Flattening the curve relies on mitigation techniques such as hand washing, use of face masks and social distancing.

Shortages related to the COVID-19 pandemic are pandemic-related disruptions to goods production and distribution, insufficient inventories, and disruptions to workplaces caused by infections and public policy.

The NHS Nightingale Hospital London was the first of the NHS Nightingale Hospitals, temporary hospitals set up by NHS England for the COVID-19 pandemic. It was housed in the ExCeL London convention centre in East London. The hospital was rapidly planned and constructed, being formally opened on 3 April and receiving its first patients on 7 April 2020. It served 54 patients during the first wave of the pandemic, and was used to serve non-COVID patients and provide vaccinations during the second wave. It was closed in April 2021.

An open-source ventilator is a disaster-situation ventilator made using a freely licensed (open-source) design, and ideally, freely available components and parts. Designs, components, and parts may be anywhere from completely reverse-engineered or completely new creations, components may be adaptations of various inexpensive existing products, and special hard-to-find and/or expensive parts may be 3D-printed instead of purchased. As of early 2020, the levels of documentation and testing of open-source ventilators was well below scientific and medical-grade standards.

Allison Joan McGeer is a Canadian infectious disease specialist in the Sinai Health System, and a professor in the Department of Laboratory Medicine and Pathobiology at the University of Toronto. She also appointed at the Dalla Lana School of Public Health and a Senior Clinician Scientist at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and is a partner of the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. McGeer has led investigations into the severe acute respiratory syndrome outbreak in Toronto and worked alongside Donald Low. During the COVID-19 pandemic, McGeer has studied how SARS-CoV-2 survives in the air and has served on several provincial committees advising aspects of the Government of Ontario's pandemic response.

Proning or prone positioning is the placement of patients into a prone position so that they are lying on their front. This is used in the treatment of patients in intensive care with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). It has been especially tried and studied for patients on ventilators but, during the COVID-19 pandemic, it is being used for patients with oxygen masks and CPAP as an alternative to ventilation.

The COVID-19 pandemic has impacted hospitals around the world. Many hospitals have scaled back or postponed non-emergency care. This has medical consequences for the people served by the hospitals, and it has financial consequences for the hospitals. Health and social systems across the globe are struggling to cope. The situation is especially challenging in humanitarian, fragile and low-income country contexts, where health and social systems are already weak. Health facilities in many places are closing or limiting services. Services to provide sexual and reproductive health care risk being sidelined, which will lead to higher maternal mortality and morbidity. The pandemic also resulted in the imposition of COVID-19 vaccine mandates in places such as California and New York for all public workers, including hospital staff.

The treatment and management of COVID-19 combines both supportive care, which includes treatment to relieve symptoms, fluid therapy, oxygen support as needed, and a growing list of approved medications. Highly effective vaccines have reduced mortality related to SARS-CoV-2; however, for those awaiting vaccination, as well as for the estimated millions of immunocompromised persons who are unlikely to respond robustly to vaccination, treatment remains important. Some people may experience persistent symptoms or disability after recovery from the infection, known as long COVID, but there is still limited information on the best management and rehabilitation for this condition.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on hospitals became severe for some hospital systems of the United States in the spring of 2020, a few months after the COVID-19 pandemic began. Some had started to run out of beds, along with having shortages of nurses and doctors. By November 2020, with 13 million cases so far, hospitals throughout the country had been overwhelmed with record numbers of COVID-19 patients. Nursing students had to fill in on an emergency basis, and field hospitals were set up to handle the overflow.